Supersedes: CAPR 10-1 07 November 2016 OPR: CAP/DA

Distribution: National CAP website

CAPP 1-2

01 October 2021

The CAP Guide to

Effective Communication

NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS CIVIL AIR PATROL

Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

2

“This report, by its very length, defends itself

against the risk of being read.”

Winston Churchill

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

3

Table of Contents

Preface ........................................................................................................................................... 4

Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 4

Before You Get Started .................................................................................................................. 4

Branding ......................................................................................................................................... 6

We Need to Have a Meeting! ......................................................................................................... 7

Can We Talk? ................................................................................................................................ 10

Presentations ............................................................................................................................... 12

I Want To See That In Writing ...................................................................................................... 14

Getting A Head Start – Using Letterhead ................................................................................. 19

The Memorandum Style Letter ................................................................................................ 20

The Business Style Letter ......................................................................................................... 33

Electronic Communications ......................................................................................................... 39

Email ......................................................................................................................................... 39

Email Signature Block ............................................................................................................... 43

Social Media ............................................................................................................................. 43

CAP Publications .......................................................................................................................... 44

Directive Publications ............................................................................................................... 44

Nondirective Publications ........................................................................................................ 45

Forms, Certificates and Visual Aids…Oh My! ........................................................................... 45

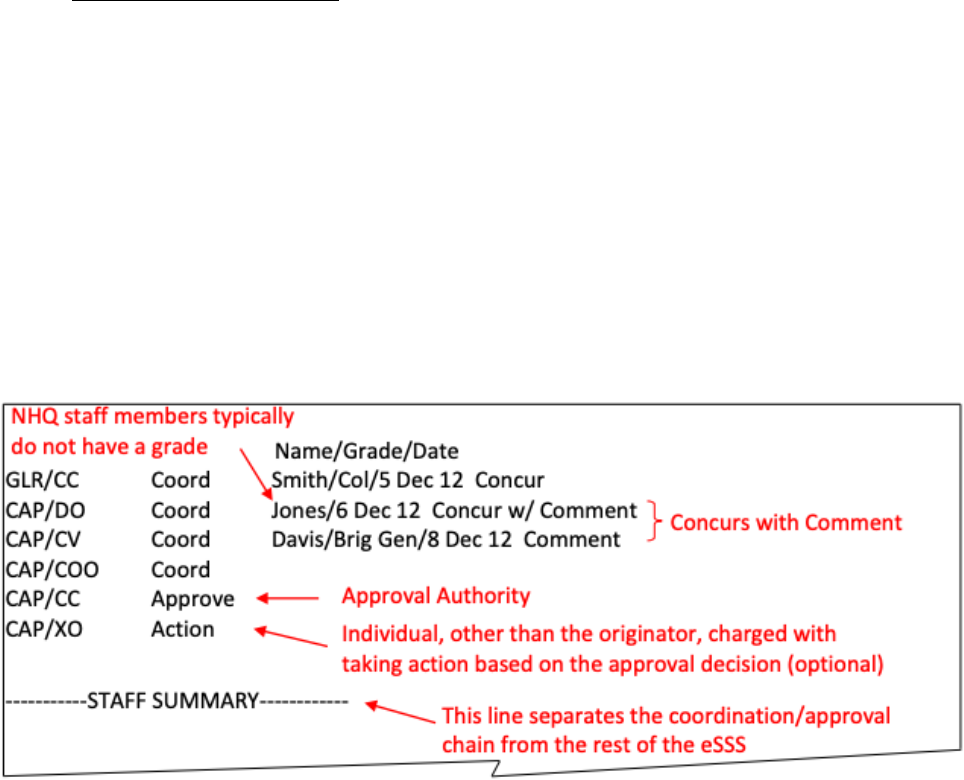

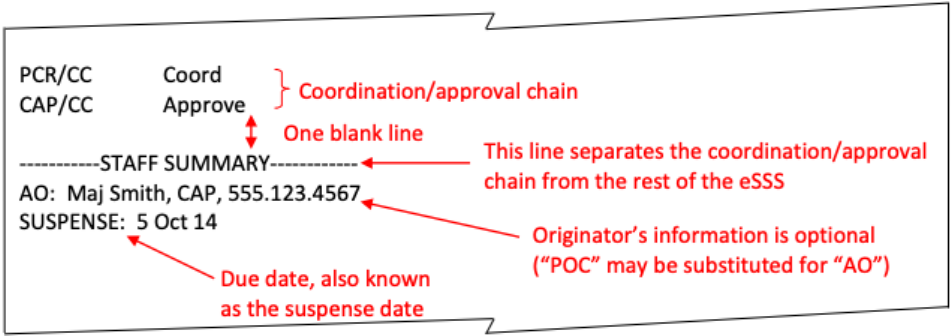

I Need Approval?? The Secret to Good Staff Work ..................................................................... 46

Electronic Staff Summary Sheet (eSSS) .................................................................................... 48

Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 53

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

4

PREFACE

This pamphlet complements Civil Air Patrol 1-series Regulations, as well as other publications.

It is designed to assist members in preparing Civil Air Patrol (CAP) publications and official

correspondence pertaining to CAP matters. This pamphlet also offers techniques for how to

conduct effective meetings and speaking engagements. Following the recommended

considerations, styles and techniques in this pamphlet promotes a consistently professional

look and sound of one CAP.

OVERVIEW

The effectiveness of any conversation is a direct result of the actions of both the speaker and

the listener. Likewise, the effectiveness of any document is often the direct result of the

actions of the person doing the writing. Regardless of whether the message is written or

spoken, the crucial point remains the same – the receiver must clearly understand the message.

The principles behind effective speaking are nearly identical to those of effective writing.

Therefore, most techniques and styles presented in this pamphlet are applicable to both

spoken and written communication.

BEFORE YOU GET STARTED

Below offers some general rules of thumb to consider when preparing for a speaking

engagement, including routine meetings, or written correspondence.

a. Put simply, you must know your intended audience. When speaking or writing, do so to

the audience’s level or to their shared understanding of the subject matter. Talking over

your audience’s heads is just as non-productive as talking beneath their level of

comprehension. The end result in both cases remains the same – you’ll lose your

audience’s attention.

b. Speak and write using plain language. Prepare all CAP correspondence and present

talking points using plain language. Plain language saves time, effort, and money while

improving the odds on your message being understood. Plain language means using

logical organization and common, everyday words, except for necessary technical terms.

For more plain language techniques, check http://www.plainlanguage.gov.

“I know that you believe you understand what you think I said, but I’m not

sure you realize that what you heard is not what I meant.”

Robert McCloskey

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

5

c. Speaking of using plain language, use a spelling and grammar checker too. Most word

processing and email programs include them. You can configure them to work

automatically which could save you much embarrassment down the road. Let’s face it;

the last thing you want is to spend time crafting a professional letter only to have it sent

containing typos and poor grammar.

d. Organize your material to help the reader/listener. Identify your audience for the

document; write or speak to get their attention and anticipate their questions. Always

start by putting your main message up front. Present information in subsequent

paragraphs/slides in a logical order. See the section on Presentations for more

information.

e. Keep in mind that in today’s electronic age your correspondence or recordings of

presentations, such as webinars, may be shared around the globe via the internet, with

or without your consent. Internet search engines find everything! As such, keep it

professional and consider that your correspondence may be referenced in other

documents and viewed by unknown audiences.

f. Structure your communication

with your audience in mind.

Consider that your audience may

not be familiar with some

abbreviations, may not share your

technical expertise on a subject or

just may have a limited background on your topic. Define each abbreviation or acronym

the first time used by writing out the full term followed by the abbreviation or acronym

in parentheses. Use the same term consistently to identify a specific thought or object.

Use words in a way that does not conflict with ordinary or accepted usage. Ambiguous

phrasing, confusing legal terms and technical jargon could mislead your reader.

Similarly, using military or CAP jargon rather than common terminology may confuse

your audience. However, if you believe your audience shares a common understanding

of the jargon, its use might foster a better conversation.

g. A picture is indeed worth a thousand words. Pictures and tables, when used properly,

can replace paragraphs or even pages of text. Most people learn visually or through

application and practice. Using graphics in presentations speeds learning and

comprehension.

h. Use “you” and other pronouns to speak directly to your audience (active voice).

Referring to people as if they were inanimate objects may be offensive. “You”

reinforces that the message is intended for your audience. Use “we” in place of your

organization’s name. Be careful using “you” if it sounds accusatory or insulting. Instead,

put the emphasis on the organization by using “we.”

“It usually takes me more than three

weeks to prepare a good impromptu

speech.”

Mark Twain

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

6

i. Active voice is the best way to identify who is responsible for what action. To

communicate effectively, write or speak the majority (around 75%) of your sentences in

the active voice. Keep in mind that some people are uncomfortable with the direct

approach of active voice. Again, know your audience, but remain aware of the intent

and tone of your message; passive voice might not be effective when directing actions.

j. Short sentences deliver a clearer message. Your sentences should average less than 20

words; never make them longer than 40 words. Complex

“I never said most of

the things I said.”

Yogi Berra

sentences confuse your audience by losing the main point

in a forest of words. Resist the temptation to put

everything into one sentence. Break up your idea into its

logical parts and make each one the subject of its own

sentence. Cut out words that are not really necessary.

k. Never overlook the value of good guidance. There are countless resources to help you

prepare for your writing or speaking task. Air Force Handbook 33-337, The Tongue and

Quill, available on the CAP publications website under other publications, is one such

resource that offers techniques and styles for both writing and speaking engagements.

Another free resource is the Air University Style and Author Guide. Also talk with others

who might share experiences in performing what you’re being asked to do.

Additionally, there is tremendous value in dry-running your presentation with peers or

letting others read your correspondence prior to sending. Since we often use voice

inflection in reading an email or letter to your test audience, it’s best to let them read

the draft email or letter in silence to see if the reader receives the message with the

same intent you desired.

l. Finally, if you’re writing or speaking on matters pertaining to CAP, your language should

leave the recipient with a positive view of CAP. Nearly just as important is the fact that

the medium you use to share your information, such as a memorandum, presentation

or web page, should reinforce a consistent look, sound, and feel of One CAP. In short,

authors should follow CAP’s established branding standards.

BRANDING.

In the corporate world, branding is essential to developing and growing a strong customer base.

Due to the broad reach of electronic communications, branding is critical to ensuring

that all recipients and online

“Great companies that build an enduring brand have

an emotional relationship with customers that has no

barrier. And that emotional relationship is on the

most important characteristic, which is trust.”

Howard Schultz

viewers receive the same look,

sound and feel of One CAP. As a

corporation, CAP relies on

branding to ensure its customers

readily recognize CAP for the

quality services provided.

Branding is the process of

creating a unique name and image and plants this image in customer’s minds to establish

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

7

brand identity. This identity is created mainly through a consistent theme that includes, but not

limited to, the use of a single CAP logo and standardized appearance of CAP’s web pages, email

signature blocks, and business cards. The goal is to make CAP a household name with

immediate recognition of a nationwide CAP. For more information on CAP’s branding program,

refer to CAP’s Brand Portal at brand.gocivilairpatrol.com.

WE NEED TO HAVE A MEETING!

How many times have you heard “We need to have a meeting to schedule a meeting” or “Boy,

that’s an hour of my life I’ll never get back”? The truth of the matter is we’ve become a society

where meetings are the norm for the so-called conducting of business and, sadly, too many

meetings occur that are unproductive. If time truly is money, then meetings need to be

productive, mean something, and involve the right people.

There is some value to holding meetings.

a. Meetings create an opportunity for dialogue, especially when the decision maker needs

immediate input and feedback. Yes, contributors can provide input via emails, but

emails are essentially a series of one-way conversations and lengthen the decision-

making process.

b. Meetings increase awareness for all participants and promote sharing of information

and ideas across unrelated areas of expertise. The assumption, of course, is made that

the meeting is keeping the attendees’ interest, otherwise the daydreaming will begin.

c. Meetings also enable the communicating of a message from one to many at the same

time while providing clarity through question and answer. Such meetings get everyone

on the same page. Let’s face it, there’s nothing better than hearing it straight from the

horse’s . . . oops . . . commander’s mouth.

d. There’s also value in recurring meetings to present routine or mandatory updates. The

key, as always, is to make the meeting productive.

e. Finally, meetings can build camaraderie amongst colleagues. There’s no rule that states

meetings must be stuffy or boring!

“If you had to identify, in one word, the reason why the human race has not

achieved, and never will achieve, its full potential, that word would be

‘meetings’.”

Dave Barry

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

8

There are several downsides to ill-planned meetings.

a. First, meetings aren’t always needed. If the purpose is to simply share information, then

perhaps an email or document is a better way to get the message to the masses and

certainly a better use of their time.

b. Meetings can have unintended consequences. Sometimes commanders will make an

innocent comment that someone interprets as a “go do” task. Commanders should be

deliberate in tasking attendees. Furthermore, attendees should seek clarification on the

perceived task before they “go do.” Otherwise, there might be needless and wasted

effort.

c. Meetings serve to communicate information to those in attendance, with an

expectation that those in attendance will further disseminate the message. In reality,

this seldom happens as expected. The geographically separated nature of CAP greatly

complicates the effective sharing of information.

d. If not properly planned, the meeting will not serve its intended purpose. When that happens,

invariably another meeting will be scheduled. Save everyone’s time and prepare for a productive

meeting.

e. Meetings, like committees, have group dynamics. Having the wrong players at the table

could take the meeting off course. The person running the meeting should set the

boundaries and keep attendees focused on the matter at hand. Additionally, be alert

for groupthink, the phenomenon that occurs within a group of people in which the

desire for harmony or conformity in the group results in an irrational or dysfunctional

decision-making outcome.

“I don’t like to spend time in endless meetings talking about stuff that isn’t

going to get anything done. I have meetings, but they’re short, prompt

and to the point.”

Eli Broad

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

9

Keys to a successful and productive meeting:

a. It’s imperative that the right people are in attendance. Don’t hold a decision-making

meeting if the decision maker or subject matter experts are not present.

b. Define the purpose of the meeting and determine if a meeting is the best approach.

You would think it obvious that every meeting has a purpose, but sometimes people

habitually go through the motions. If a meeting is not needed – don’t hold one.

c. Pick a time and location that’s conducive to a productive meeting. Again, the

geographically separated nature of

CAP and the crossing of time zones

present challenges, but the use of

teleconferencing and online

applications such as webinars can

enable productive meetings.

“We had some very distinguished fans:

I know one chancellor of a major

university who used to schedule his

meetings around Star Trek.”

Patrick Stewart

d. Determine the best medium for conducting the meeting when members cannot be in

the same room. Teleconferencing is inexpensive, but members don’t get the luxury of

placing faces to names or voices. Video conferencing and webinars provide such a

luxury. Sites such as gotomeeting.com, gotowebinar.com, zoom.us and

hangouts.google.com are rather inexpensive and sometimes free to use. Regardless of

the medium, the individual running the meeting should remind attendees of the

following general rules of etiquette:

• State your name prior to speaking. This is more important for conference calls

where video is not an option.

• If you’re not speaking, mute the phone/microphone on your end. You are

participating in the meeting, not your barking dog.

• For video conferences, consider your backdrop for possible distractions. Yes,

you might have something important to contribute to the meeting, but other

attendees aren’t listening because they’re watching the ball game on the TV

behind you.

• Likewise for video conferences, just because you’re joining from your home

office doesn’t mean you can wear your pajamas. Dress appropriately. Keep in

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

10

mind that it’s quite easy to record online meetings and share with your closest

friends.

e. Appoint someone to record or take minutes of the meeting. The last thing you want is

for important information to be discussed or decisions to be made and nobody

remembers who said what and why. Keep in mind that meeting minutes are not play-

by-play transcripts; rather they serve to highlight the key points that were discussed.

f. Send out an agenda. It is preferable to send the agenda one week in advance of the

meeting; anything less than two days jeopardizes the meeting’s productivity. The

agenda lets attendees know the issues to be addressed, decisions to be made and

actions to be taken. Plus, the agenda lets attendees know what data to bring with them

to aid the decision-making process. Additionally, providing hard copies of the agenda

makes it easier for attendees to take notes.

g. Send out read ahead material. Providing read ahead material allows attendees to

prepare their thoughts and be able to hit the ground running once the meeting

convenes. While agendas might not be needed for routine or recurring meetings,

providing read ahead material will still save time during the meeting. Ultimately,

members should find the meeting to be more productive, filled with more meaningful

contributions, and hopefully shorter. See the section on Presentations for more

information.

h. Don’t forget that meetings can be cancelled. Go back to the first rule of ill-planned

meetings – if you don’t need one, don’t hold one. Additionally, providing read ahead

material might reveal a solution to the agenda’s issue and eliminate the need for a

meeting. Once a decision is made to cancel a meeting, let everyone know. While this

sounds obvious, people continue to show up at empty rooms or silent teleconferences.

i. If you are running a meeting, make sure you start on time, stick to the agenda, don’t let

sidebar conversations derail the train of thought, and end on time…or early.

CAN WE TALK?

“According to most studies, people’s number one fear is public speaking.

Number two is death. Death is number two. Does that sound right? This

means to the average person, if you go to a funeral, you’re better off in the

casket than doing the eulogy.”

Jerry Seinfeld

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

11

“All the great speakers were bad

speakers at first.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

“The human brain starts working the

moment you are born and never stops

until you stand up to speak in public.”

Mark Twain

It’s often been said that average person fears public speaking more than death itself. Yep, it’s

true. Glossophobia is a very real and often immobilizing fear. So, if recognition is the first step

to recovery, let’s look at some tips that might help reduce your glossophobic symptoms.

a. For starters, accept the fact that you’re no different than most when it comes to the

jitters. Even people who frequently speak in public venues will tell you they still get a

little nervous. What does help is to increase

the frequency of your speaking engagements,

even if only in staff meetings surrounded by

your colleagues. While doing so won’t settle

all of your nerves, over time you might feel

more comfortable.

b. Get organized. If your voice cracks, who cares? At least people will still be able to grasp

the message. Even the best of public speakers will lose their audience’s attention if

they’re not organized.

c. Squelch your fear of rejection. Realize you’re speaking to your audience for a reason.

You are the expert in what you’re about to present. If everyone else were the experts,

there’d be no need for an assembly. People want to hear what YOU have to say.

d. Practice does indeed make perfect. Perhaps start by speaking in front of a mirror or

record your voice and play it back. Then move up to a small audience of friends and

family. It’s like washing your hair:

lather, rinse and repeat. In this case,

give your practice presentation

several times so it’s almost as if

you’re memorizing the entire speech.

When you’re speaking for real and

the jitters are at their worst, the natural tendency will be to return to that moment

of comfort…your memory.

e. Breath, silly, breath…you forgot to breath! Focusing on your breathing will help you

relax. Sure enough, taking a deep breath helps. Also try to speak in a rhythm to keep

the flow going. Speaking in short, simple, to-the-point sentences also helps.

f. Repeat after me…a picture, or video, is worth a thousand words. But they better be

good and add to the presentation. A video that addresses your purpose could translate

into less talking from you. Videos are often used to interject levity and set you and your

audience at ease; however, caution is advised in that not all members of your audience

share the same sense of humor. Microsoft® PowerPoint® or other presentation media

can greatly enhance the effectiveness of your speaking engagement. Use of such media

can help bring you back on track if you stray or are at a loss for words. However, the

opposite effect could occur too. Don’t read slides to your audience. If that was how

you planned to present the information, then you could have emailed it to them and

saved everyone’s time. For more information, see the section below on Presentations.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

12

g. Use storytelling to help share your message. People often start their presentations with

a joke. Doing so adds levity and sets the presenter and the audience at ease as long as

everyone shares your sense of humor. Storytelling effectively serves the same purpose,

but has two distinct advantages. First, since it’s your story, you’ll easily remember it and

regaling the audience with your experiences might calm your jitters. Second, the

audience will better remember your presentation when they can relate to your story. In

this situation, the notion of “been there, done that” makes the audience feel as if

they’re part of the conversation.

h. Finally, pay attention to your audience, but don’t read too much into what you see. Are

members yawning? Well, it could be you (bummer!) or it could be you’re the first

briefer after a heavy lunch (still a bummer, but not your fault). Do they look confused?

Perhaps that’s your cue to rephrase what you just said. Watch their body language and

yours; oftentimes the audience mirrors what they see in you.

PRESENTATIONS

Meetings and speaking engagements are often more productive when using presentations or

what is commonly referred to as “slides.” Many programs, such as Microsoft PowerPoint or

Adobe® Acrobat® to name a few, are excellent products for presenting information to your

viewers. The added benefit is that you can email or post online the presentations as read

ahead material. Creating presentations requires some degree of skill or art; if not properly

developed, the slides can be more of a distracter than a helper.

Keys to a successful presentation:

a. For starters, make sure you begin slide development using CAP’s brand-standardized

template found on the CAP Brand Portal at brand.gocivilairpatrol.com. Using the

template ensures consistency in CAP presentation appearance and it also helps you

by auto- formatting slides (i.e. font style and size, bullets, color, etc.) as you create

them.

b. People don’t like “death by PowerPoint,” but that doesn’t mean you have to cram

everything into one slide. Slides should highlight the key points of your discussion, but

not every word you plan on saying. They should be simple enough that the audience

can read the slides and still listen to what you’re saying. For example:

“Public speaking is the art of diluting a two-minute idea with a two-hour vocabulary.”

John F. Kennedy

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

13

c. The same goes for the size of the font. Each slide should be readable from any seat in

the house. Not only do you need to know your audience, but you also need to know

your venue and presentation equipment.

d. Animation, when used effectively, can add an impressive flair to a presentation.

However, don’t overuse animation. People often use animation to transition from one

slide to another or to “build” the slide as you’re discussing it to prevent the audience

from reading ahead. The problem is these transitions and “builds” are usually too slow

and, when added up, can increase the duration of the presentation. Additionally,

repetitive animation gets boring. Bottom line – there’s a time and place for everything

so use animation wisely.

e. As mentioned previously, video and pictures are worth a thousand words. Adding video

to a presentation can promote subject matter comprehension. However, imbedding

video into a presentation can be finicky. Just because it worked on your home

computer doesn’t mean that the video will perform flawlessly when you present it at

your speaking engagement, usually on a borrowed computer. Make sure you dry-run

your presentation on the computer to be used for delivering it.

f. Make sure your content flows seamlessly from start to finish. Think of your

presentation as a story that has a beginning and middle that ultimately lead to a logical

conclusion. To think of it a different way, imagine someone telling a joke where they

start off with the punch line. It just doesn’t make sense and neither will your

presentation if it doesn’t flow.

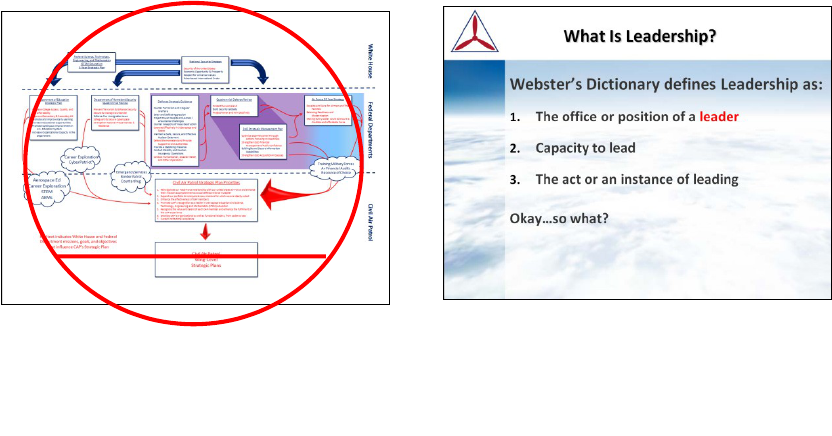

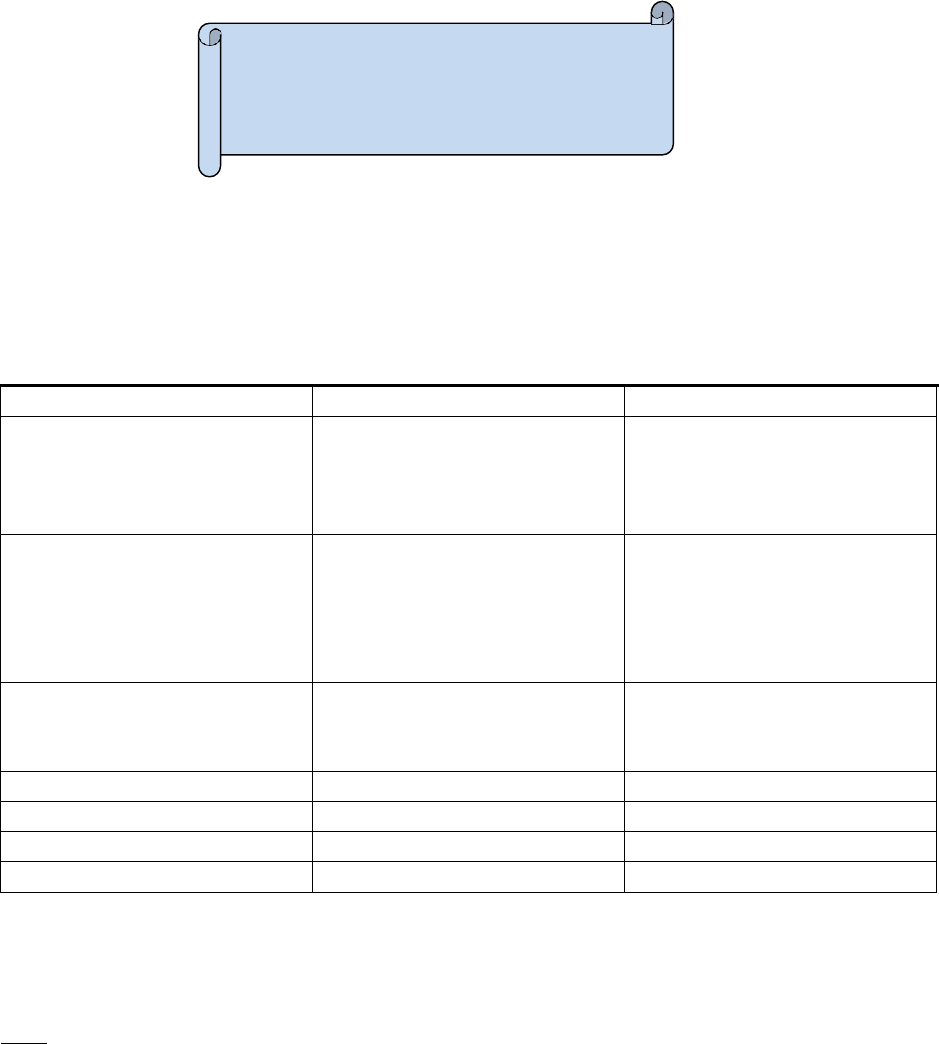

g. Finally, the structure of the slides can add consistency and improve the meeting’s

productivity and predictability, especially for recurring events such as staff and progress

update meetings. Oftentimes the structure is determined by the person leading the

meeting, for example the unit commander or the director of an Emergency Operations

Center. A slide structure known as the “quad chart” is commonly used due to its

simplicity and to-the-point display of information. In practice, each quadrant has a title

Don’t be this guy, unless of course

you’re trying to make a point…or

you don’t want any friends!

Good example – clean, simple and

easy to read. It’s also presented on

the CAP brand-standardized slide.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

14

“When I was growing up, my mother would always say, ‘It will go on your permanent

record.’ There was no ‘permanent record.’ If there were a ‘permanent record,’ I’d

never be able to be a lawyer. I was such a bum in elementary school and high school.

There is a permanent record today, and it’s called the internet.”

Alan Dershowitz

and supporting bullets. The quadrant titles will vary with the meeting’s purpose or

desires of the lead person. An example of a quad chart is shown below.

I WANT TO SEE THAT IN WRITING

It is one thing to speak to an audience, but the real proof is found in written correspondence.

And proof it is. If you sign your name to it, or the correspondence came from your email or

social media account, it becomes difficult to say you didn’t write it. As mentioned previously, it

must be assumed that anything posted online, to include emails and social media sites, is visible

to the entire world. Oh, and if it’s on the internet, it’s there forever. That’s not said to scare,

rather it’s mentioned as a word of caution to ensure what you write is always professional and

reflects favorably on the Civil Air Patrol.

Quad chart titles vary with the needs

of the meeting or the discretion of the

person running the meeting

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

15

Most written CAP correspondence fall into one of three types. The purpose, audience and

desired “professional impact” determine which type to use. Templates for the memorandum

and business style letters can be found on the CAP publications website.

a. Memorandum Style Letter. This style is used for correspondence between CAP units

and when communicating with military agencies.

b. Business Style Letter. This style is used for correspondence with private concerns and

individuals not connected with CAP.

c. Electronic Mail (Email). Email is often an appropriate substitute for an official style

letter. Email also serves as the preferred avenue for coordinating publication revisions

or other actions requiring approval. This coordination is usually referred to as the

electronic Staff Summary Sheet, or eSSS for short.

Other types of CAP written correspondence include, but are not limited to:

a. Meeting Minutes. Minutes become the record of what occurred during a meeting. Of

most value are the issues discussed and the decisions made, to include the debate, to

resolve the issue.

b. Personalized Letters. These letters serve many purposes. Most often, personalized

letters are written to show gratitude for an individual’s contributions or to foster

partnerships.

c. Point Papers. The papers serve as memory ticklers or quick-

reference outlines to use during meetings or to informally pass

information quickly to another person or office. The format is similar

to a talking paper.

d. Talking Papers. A talking paper is a quick-reference outline on key

points, facts, positions, and views of others to use during oral

presentations.

e. Background Papers. A background paper serves as its name

implies, it provides the reader with a summarized chronological

background of an issue, the current matter to be addressed and

possible courses of action.

f. Position Papers. These papers evaluate a proposal, raise a new

idea for consideration, advocate a current situation or proposal, or

“take a stand” on an issue. Position papers are sometimes referred to

as advocacy papers.

For more

information

on these

papers,

refer to Air

Force

Handbook

33-337

The Tongue

and Quill

Or see the

templates

on the CAP

publications

web page.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

16

Summary of Air Force Style Papers

Form

Function

Point Paper

• Single issue

• Single page

• Bullets or phrases

• Minimal data

Memory jogger: minimal text outline of a

single issue to quickly inform others

extemporaneously (no-notice)

• Conveys a single, narrow message in a very

short time, such as with an “elevator

speech”

• Give the same short message many times

• Requires prior research and content

memorization

Talking Paper (TP)

• Single issue

• Single page

• Bullets or phrases

• Key reference data

Speaking notes: outlines and narrates a single

issue to inform others during

planned/scheduled oral presentations

• Serves as a quick reference on key points,

facts, positions

• Addresses frequently asked questions

• Can stand alone for basic understanding of

the issue

Bullet Background Paper (BBP)

• Single issue or several related issues and

impact

• Single or multi-page

• Bullet statements

Background of a program, policy, problem or

procedure; may be a single issue or

combination of several related issues

• Concise chronology of program, policy,

problem, etc.

• Summarizes an attached staff package

• Explains or details an attached talking paper

Background Paper

• Single issue or several related issues and

impact

• Multi-page

• Full sentences, details

• Numbered paragraphs

Multipurpose staff communications

instrument to express ideas or describe

conditions that require a particular staff

action

• Detailed chronology of program, policy,

problem, etc.

• Condenses and summarizes complex issues

• Provides background research for oral

presentations or staff discussions; informs

decision makers with details

Position Paper

• Single issue or several related issues and

impact

• Multi-page

• Full sentences, details

• Numbered paragraphs

Working with proposals for new program,

policy, or procedure, or plan for working a

problem

• Circulate a proposal to generate interest

(initiate the idea)

• Evaluate a proposal (respond to another’s

idea)

• Advocate a position on a proposal to

decision makers

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

17

g. Forms. Yes, believe it or not, forms are another type of written correspondence.

h. Greeting and Note Cards. Short and to the point, these cards make a memorable impact

with visitors and new members.

i. Hand-written Notes. In the electronic age, hand-written notes are seldom used.

However, authors should never underestimate the impact these notes make with the

receiver. The fact that the author takes the time to prepare a hand-written note

conveys sincerity in the message.

Military style documents possess a language of their own, often using acronyms to shorten

common phrases or when referring to office symbols. This is not unique to military agencies as

many federal, state and local government agencies have their own style. It is preferred for

authors to write in the style of their intended recipient.

CAP is no different. Given our close association to the Air Force, we too use our own acronyms

and office symbols. Office symbols are shortcuts representing the organization structure and

functional responsibility. Office symbols may be used on correspondence, e-mail, forms, etc.

Major functions have two-letter symbols, for example, director of operations (DO). Since basic

functions report to major functions, basic functions have three-letter (or more) symbols. For

example, the emergency services officer is expressed as DOS. A basic function’s office symbol

starts with the same letters as the parent function’s office symbol, and adds one more letter. In

this case, the emergency services training officer is represented by DOST and the assistant ES

officer would be DOSA.

There is one exception to the two-letter office symbol. CAP’s Chief Operating Officer is

identified as CAP/COO, a position reflecting CAP’s corporate status and common across many

industries.

Office symbols may be used alone (CC) or with the organization designation (CAP/CC). Some

office symbols apply to specific command levels or organizations. For example, GLR/XX for

Great Lakes Region, MIWG/XX for Michigan Wing, MI248/XX for Kellogg Senior Squadron, or

CAP-USAF/XX for Headquarters CAP-USAF. Shown on the next page are commonly used CAP

office symbols.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

18

Commander .......................................... CC

Vice Commander ................................... CV

Deputy Commander .............................. CD

Deputy Commander for Cadets ......CDC

Deputy Commander for Seniors ..... CDS

Chief Operating Officer (NHQ only) ... COO

Chief of Staff ...........................................CS

Deputy Chief of Staff ....................... DCS

Command Chief Master Sgt ................. CCC

Executive Officer ...................................XO

First Sergeant ...................................... CCF

(Cadet or Composite Squadrons only)

Administration ......................................DA

Aerospace Education ............................ AE

Cadet Programs ..................................... CP

Chaplain ................................................. HC

Communications (Director) ................... DC

e-Learning (NHQ only) ............................ EL

Finance ................................................. FM

Wing Financial Analysts.................. FMA

General Counsel (NHQ only) ................. GC

Government Relations Advisor ..............GR

Government Relations (NHQ only) .....GVR

Health Services ...................................... HS

Historian ............................................... HO

Human Resources (NHQ only) ...............HR

Information Technology...........................IT

Inspector General ................................... IG

Legal Officer ........................................... JA

Logistics ................................................. LG

A/C Maintenance Officer ............... LGM

Supply Officer ................................. LGS

Transportation Officer .................... LGT

National Operations Center................ NOC

Operations ............................................ DO

Communications (NHQ only).......... DOK

Counterdrug ................................... DOC

Emergency Services ........................DOS

Homeland Security ......................... DOH

Operations Training........................ DOT

Standardization & Evaluation ........ DOV

Personnel .............................................. DP

Plans and Programs ............................... XP

Professional Development .................... PD

Public Affairs ......................................... PA

Safety .....................................................SE

Wing Administrator (NHQ employee) ..WA

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

19

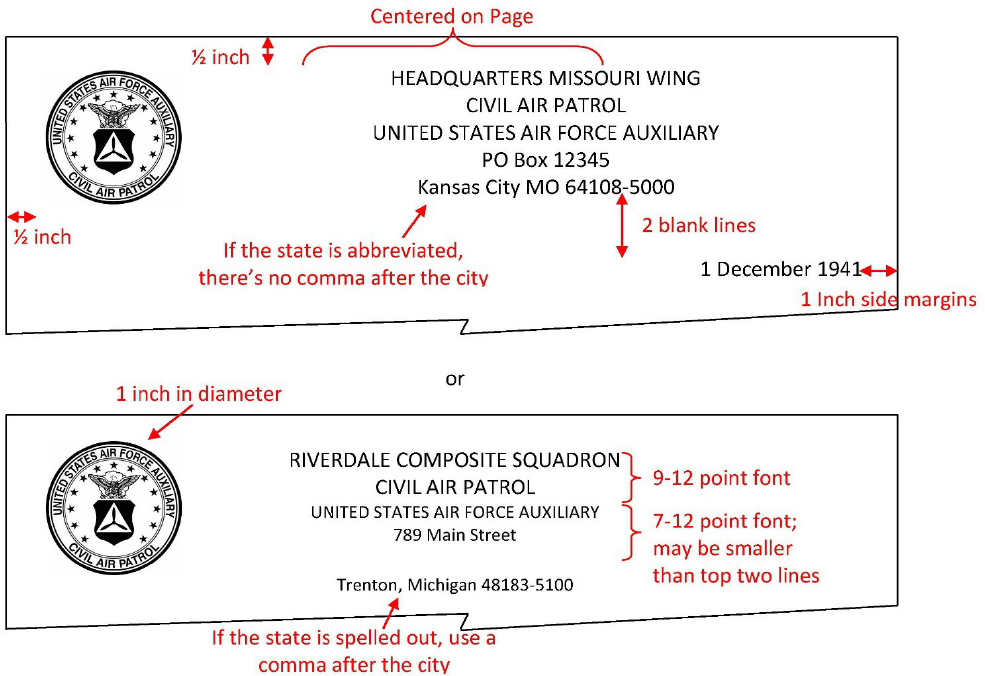

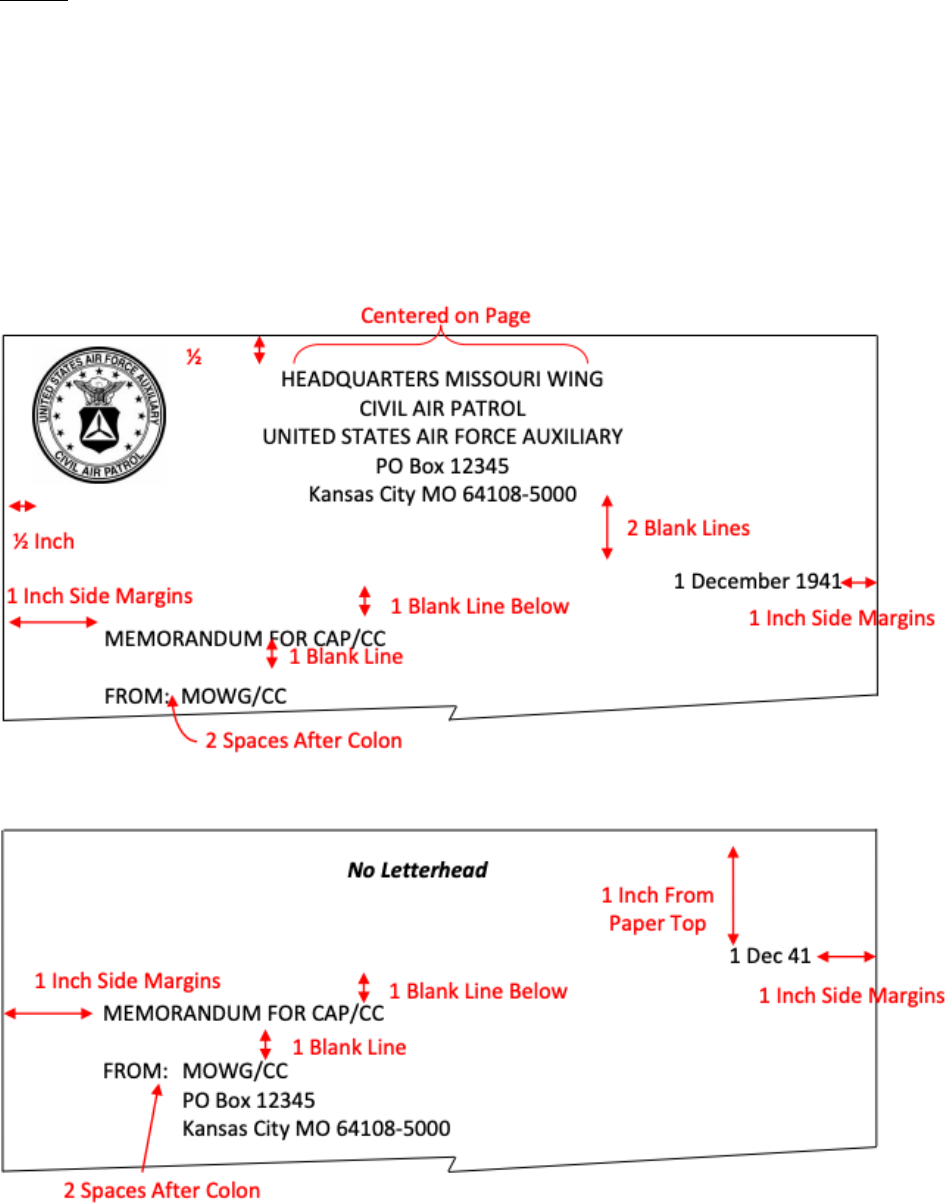

Getting A Head Start – Using Letterhead

Preprinted letterhead is preferred when writing a memorandum or business style letter. The

use of preprinted letterhead is optional for other types of written correspondence. Preprinted

letterhead standardizes the look of professional correspondence and draws the reader’s

attention to the CAP brand.

CAP’s standard letterhead includes these elements: unit designation; the words "Civil Air

Patrol"; "United States Air Force Auxiliary"; and the geographic location of the unit. The words

"United States Air Force Auxiliary" and the geographical information may be a smaller font than

the unit designation and “Civil Air Patrol”. For example:

Letterhead starts 1/2 inch from the top edge and is centered on the page. Letterhead should

be in a sans serif style font, meaning that the letters do not have a “tail,” “feet” or other

decorative flourishes. For example:

Apple (Times New Roman serif font) Apple (Calibri sans serif font)

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

20

Calibri is the preferred font, especially if you anticipate the document being viewed online.

Studies have shown that serif style fonts are easier to read in printed format while sans serif

fonts are more easily read online.

The CAP seal is used on the memorandum style letter. For all other correspondence, the CAP

seal, CAP emblem, unit patch/emblem, or other distinctive decoration may be printed on the

letterhead as long as it is in good taste (Refer to CAPR 900-2, Use of Civil Air Patrol Seal and

Emblem; Use and Display of the United States Flag and Civil Air Patrol Flags, for instructions on

use and illustrations of the CAP seal and emblem).

The CAP seal is 1 inch in diameter. Unit distinctive patches/emblems are 1 inch wide. Align the

seal/patch/emblem 1/2 inch from the left and top edges of the paper. If a higher headquarters

seal is placed in the upper left corner, subordinate units may add their unit seal/patch in the

upper right corner. The unit seal/patch is also 1 inch wide; however, it’s positioned 1/2 inch

from the right and top edges of the paper.

CAP seal graphics are available on the CAP Brand Portal at brand.gocivilairpatrol.com.

Email Memorandum. Letterhead may be superimposed into an email that is intended to be an

official correspondence. The heading element normally applies to a hard copy memorandum or

to a memorandum prepared as an attachment to an e-mail, but may be used in a memorandum

style email as well.

The Memorandum Style Letter

The memorandum style letter serves as an official communication internal to CAP as well as

military agencies. It may also be used when writing to other government agencies; however,

some agencies might be more receptive to the business style letter so it helps to know your

audience. The letter is typically written on standard 8 ½ by 11 inch white paper; however, an

alternate email version is acceptable to a CAP recipient.

The memorandum style letter has several elements, each discussed in detail below. These

elements are: heading element, body, closing element, attachment element, courtesy copy

element, and endorsements.

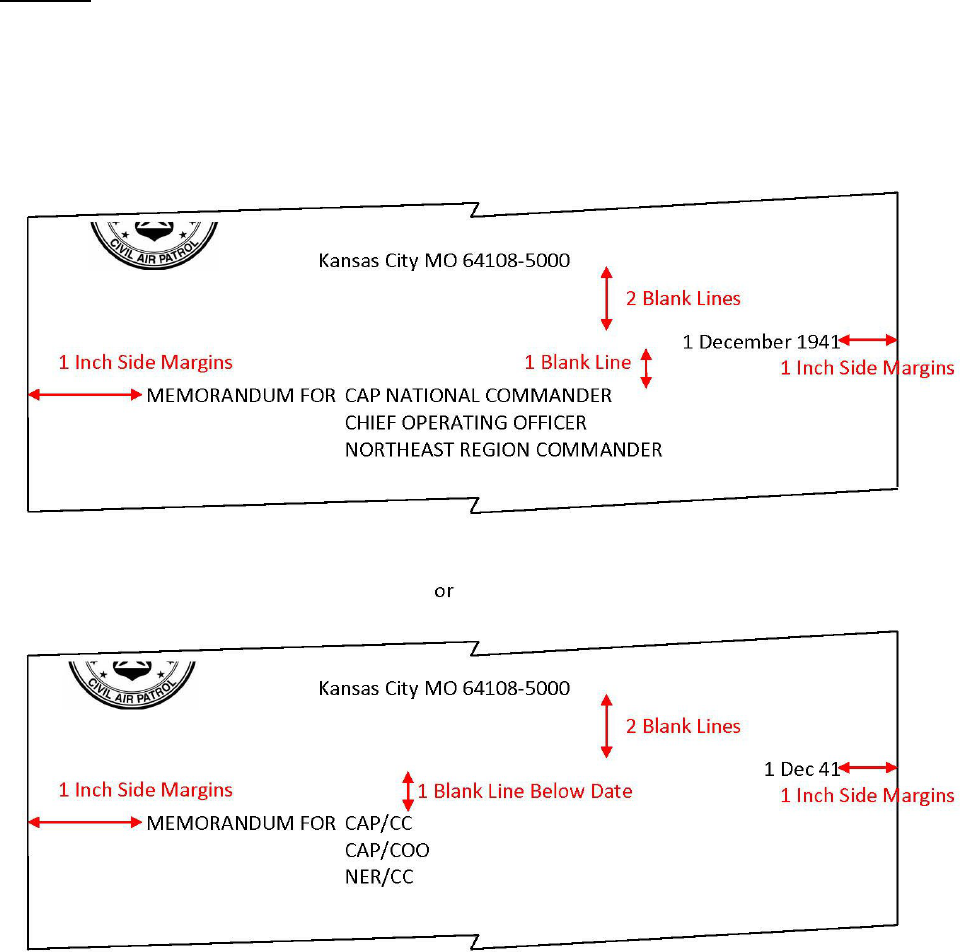

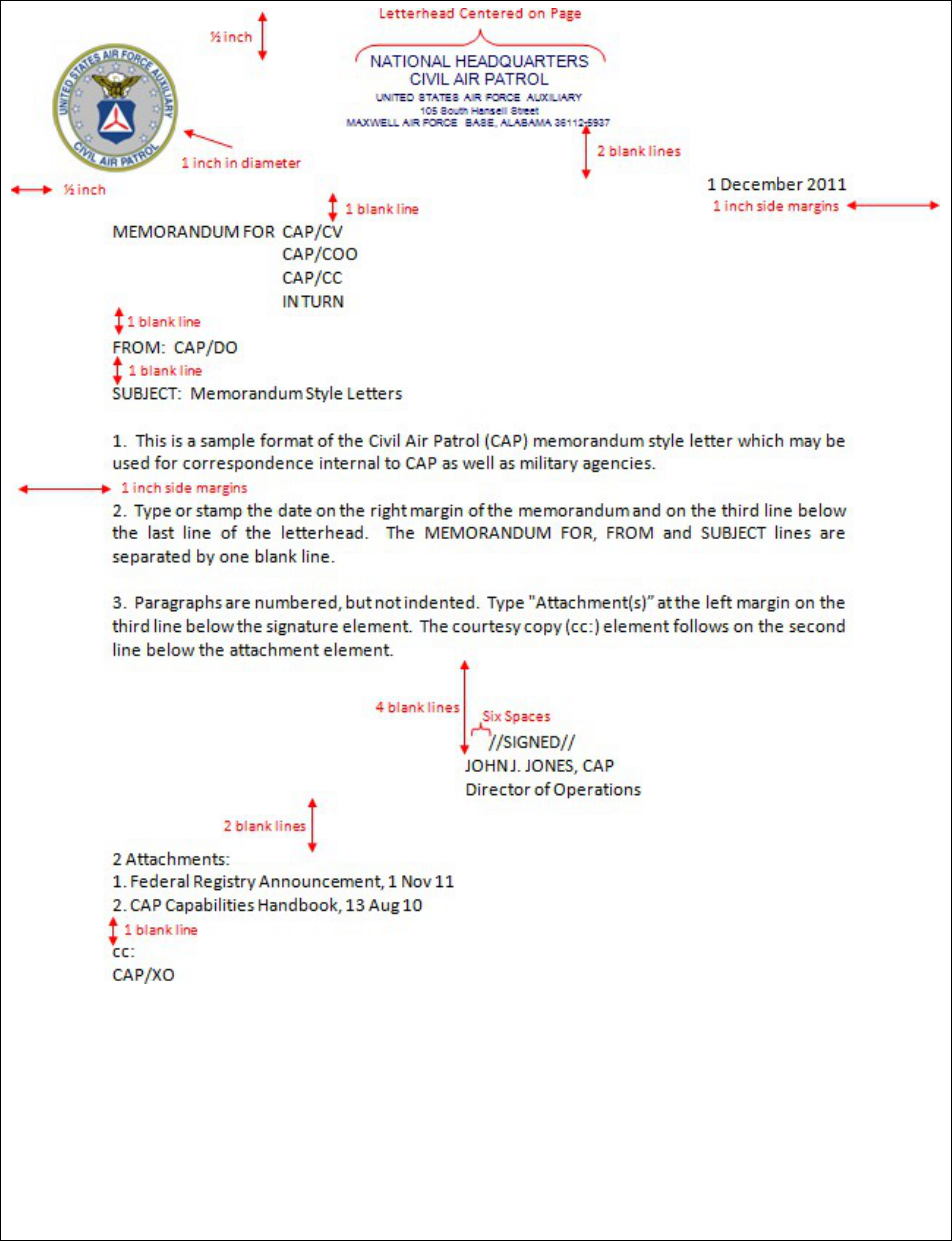

Heading Element. The heading element of the memorandum style letter includes the date, the

recipient(s), the sender, and the subject. This format is standardized for both paper and

electronic memorandum letters.

Date. Type or stamp the date on the right margin of the memorandum and on the third line

below the last line of the letterhead (Note: if no letterhead is used, place the date 1 inch from

the top edge of the page). Indicate the date in the format of day, month, and year; for

example, 6 Jun 12 or 6 June 2012. As a general rule, when the month is shortened, such as Aug,

then the year is shortened to the last two digits. When the month is spelled out, such as

August, the date is completed with the four-digit year. Unless the date of signature has legal

significance, date the original and all copies of the correspondence at the time of dispatch.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

21

However, you should date correspondence prepared for reproduction with the date it will enter

the distribution system.

Recipient. The recipient of the letter is indicated on the MEMORANDUM FOR. The

MEMORANDUM FOR line begins on the second line below the date. Multiple recipients of the

same memorandum are listed below and in line with the first recipient, in order of precedence.

The MEMORANDUM FOR line is typed in all capital letters, spelling out the entire name or

position of the recipient. As an alternative, it is acceptable to abbreviate organizational office

symbols. Be consistent and use the same format throughout. For example:

When your list of addressees is too long to list in the heading, you may enter "MEMORANDUM

FOR DISTRIBUTION" and place the distribution list on a separate page attached to the

memorandum. An alternative is to list the recipients on the last page of the letter, two lines

below the attachment or "cc:" (courtesy copy) elements, if used, or in their place if not used.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

22

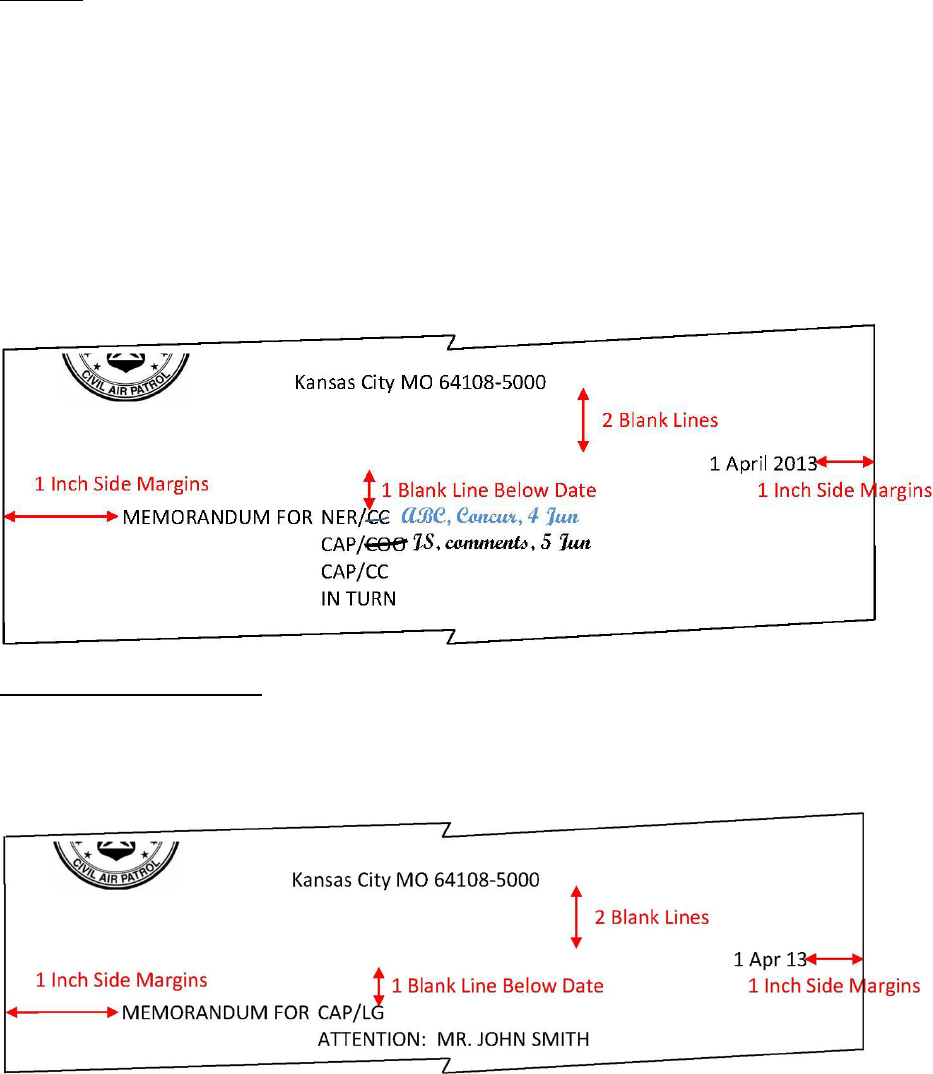

IN TURN. An "IN TURN" memorandum is used when you want to send the correspondence to

several recipients in sequence. It’s primarily used when the sender wants the final recipient to

see the coordination or action of the other recipients as the memo moves along the chain.

Unlike the above example where multiple recipients are listed in order of precedence, the IN

TURN memorandum is listed in reverse order of precedence. Align "IN TURN" under the first

word of the last addressee. In practice, recipients of a paper memorandum would line through

their office, initial, annotate concurrence/comments and date after their address signifying

receipt and acknowledgement. If comments are made, attach them to the memorandum prior

to forwarding to the next addressee. For email memorandums, receipt and acknowledgement

is usually reflected in the forwarded email thread, along with any comments. Here’s an

example of a paper IN TURN memorandum:

ATTENTION and THROUGH. If you address your memorandum to an office, but want a

particular person to receive it, use an "ATTENTION:" or "THROUGH:" line placed immediately

below and in line with the addressee’s office. This line may be shortened to read "ATTN:" or

"THRU:" in all caps. Here’s what an ATTENTION addressee should look like:

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

23

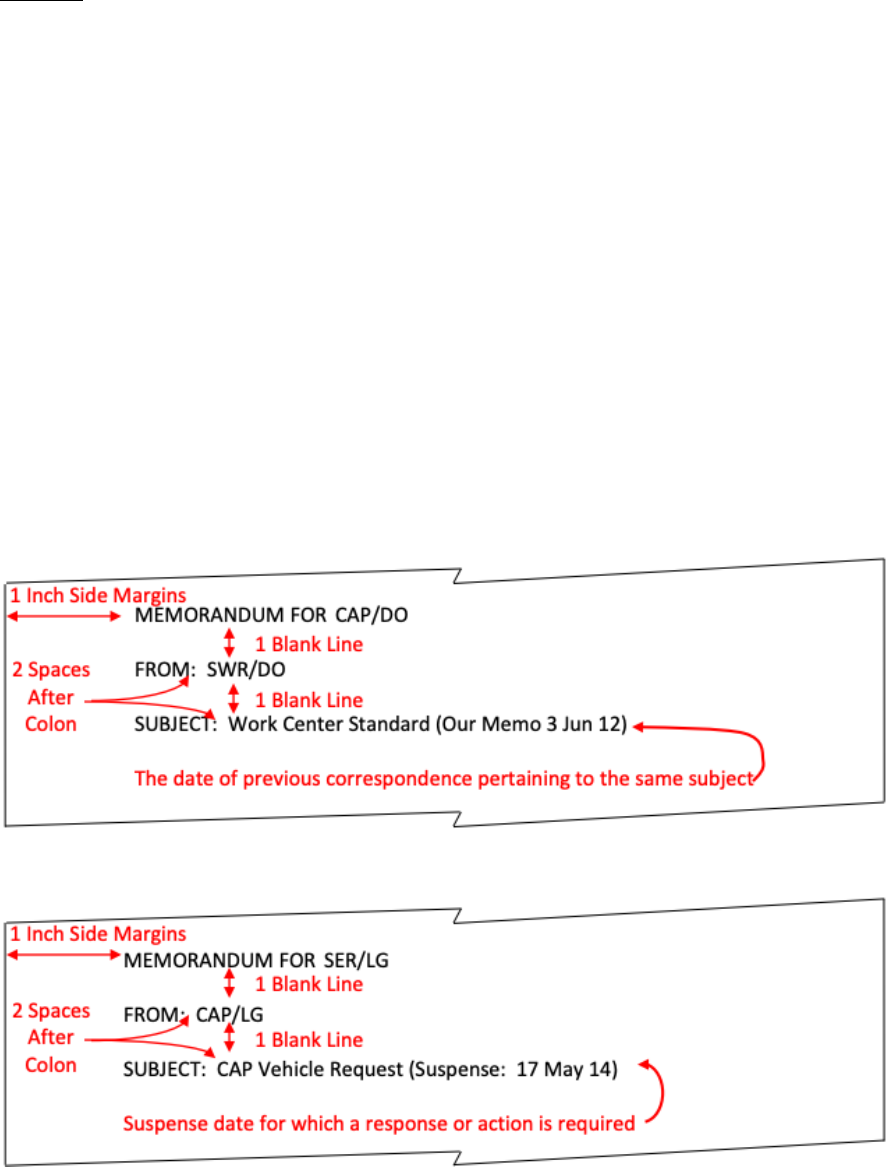

Sender. The sender is indicated on the “FROM: ” line; however, unlike the MEMORANDUM

FOR line, only the word FROM, or office symbols if used, are spelled in all capital letters. The

FROM line is entered on the second line below the last line of the MEMORANDUM FOR section.

If the letterhead contains the organization’s full mailing address, only the sender’s office

symbol is needed. If the full mailing address of the sender originating the correspondence is

not in the letterhead or there is no letterhead, the first line includes the organization

abbreviation and office symbol. Enter the delivery address (street or PO Box number), room or

suite number, and then the city, state, and zip code on the next two lines. If you wish to

include contact names, fax numbers, phone numbers or e-mail addresses, place them in the last

paragraph of the letter’s body. Here are two examples to show you how this should appear:

or

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

24

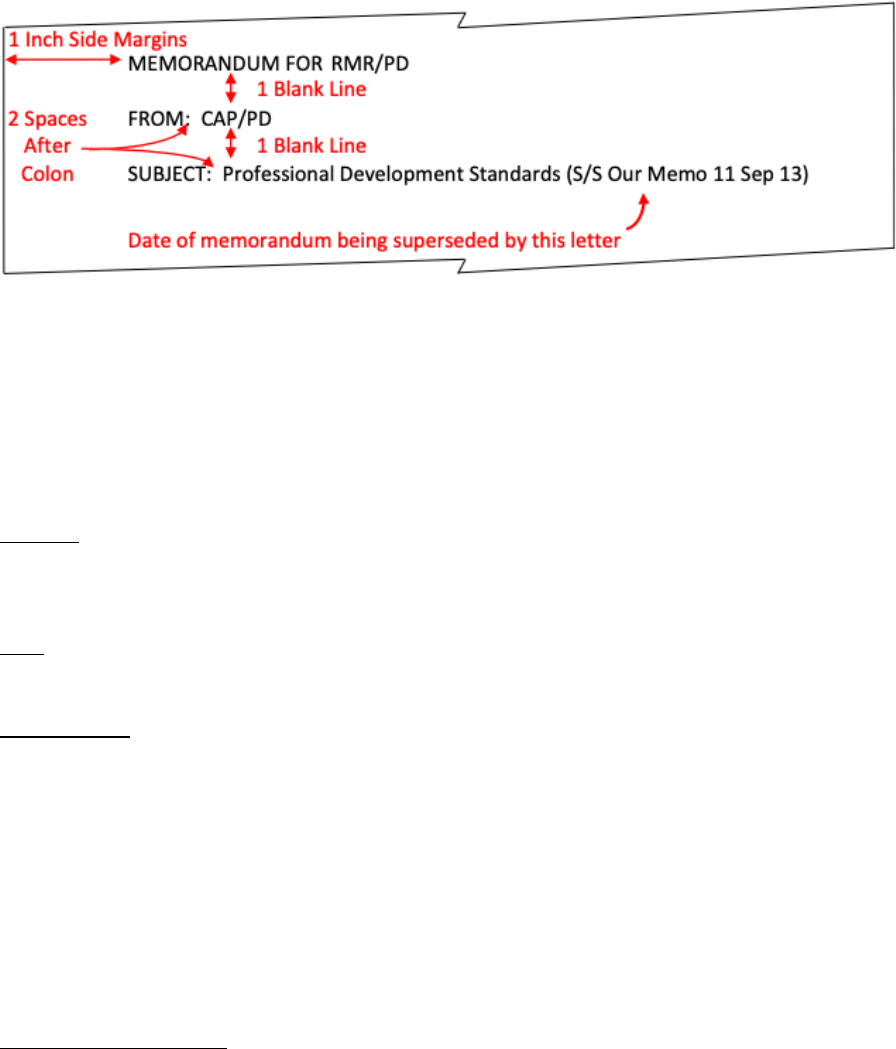

SUBJECT. The SUBJECT is nothing more than the title of the memorandum that summarizes the

letter’s content. Type "SUBJECT:" in all capital letters on the second line below the last line of

the "FROM" section. SUBJECT is the only word spelled in all capital letters; the remainder is

spelled using Title Case except for words, such as acronyms, that are always fully capitalized. As

a general rule, capitalize all words with four or more letters. Words with fewer than four letters

are capitalized except for:

a. Articles: the, a, an

b. Short conjunctions: and, as, but, if, or, nor

c. Short prepositions: at, by, for, in, of, off, on, out, to, up

If you need a second line, begin it directly under the first word of the subject’s first line. If you

refer to an earlier communication to or from the addressee on the same subject, or to another

correspondence or a directive, cite it in parentheses immediately after the subject. Send a copy

of the referenced correspondence if you feel the reader may not have it. Here are a few

examples:

or

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

25

If the correspondence supersedes a previous correspondence, you may place a statement in

the subject line. Use "S/S" to indicate supersession, as indicated below:

Body. The body makes up the substance of the memorandum. Just like a speaking

engagement, the letter’s body should get to the point and provide sufficient information to

make sure the reader understands your message. Active voice is preferred; however, some

readers may find the message too direct. Passive voice softens the message, but often requires

more words and could change the tone or clarity of the message. Bottom line – know your

audience.

Margins. As indicated earlier, standard margins on hard copy letters should be 1 inch from all

edges of the paper. The one exception is letterhead, which is placed ½ inch from the top and

sides. The remainder of the letter is framed with 1-inch margins.

Font. Given that most documents are passed electronically and viewed online, the preferred

font for memorandum letters is Calibri, a sans serif style font.

Paragraphing. The memorandum body, either in paper or email format, starts on the second

line below the last line of the subject. Main paragraphs are numbered and not indented, with a

blank line between paragraphs. Subparagraphs are lettered. A single paragraph is not

numbered. In other words, there is no “1.” if you don’t have a second paragraph. This same

rule applies to subparagraphs; if there is only one subparagraph, then it’s better to make it a

main paragraph.

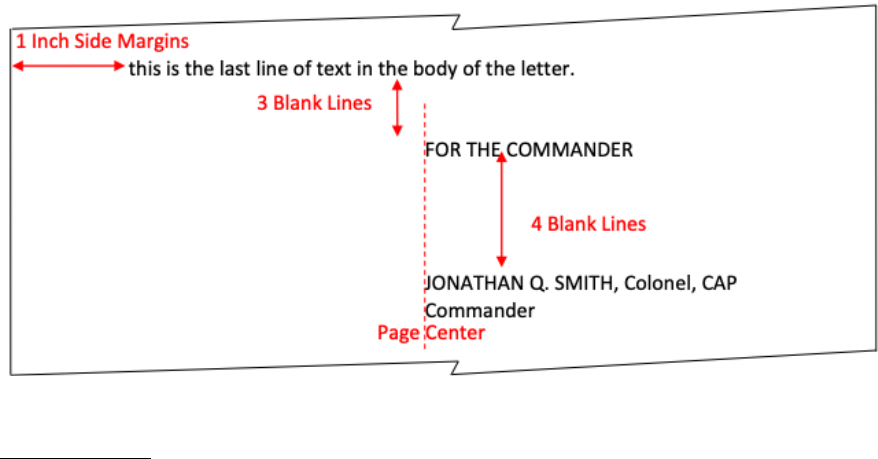

Closing Element. The closing element is nothing more than the signature block, which starts at

page center and on the fifth line after the last paragraph in the body. There is one exception to

this rule – FOR THE COMMANDER.

FOR THE COMMANDER. This phrase is used only on the memorandum style letter and only

when the author is directed to write correspondence, or if the author is issuing correspondence

that would normally be issued by the commander. FOR THE COMMANDER begins at page

center and on the third line below the last line of text. The commander’s signature block

follows on the fifth line. For example:

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

26

Signature Block. The signature block identifies who is releasing the letter, which may be

different than the author. The signer is the person with authority to release the letter and,

once signed, is an indicator they agree with the letter’s content, regardless of who wrote it.

The writer’s signature is placed in the space immediately above the signature block.

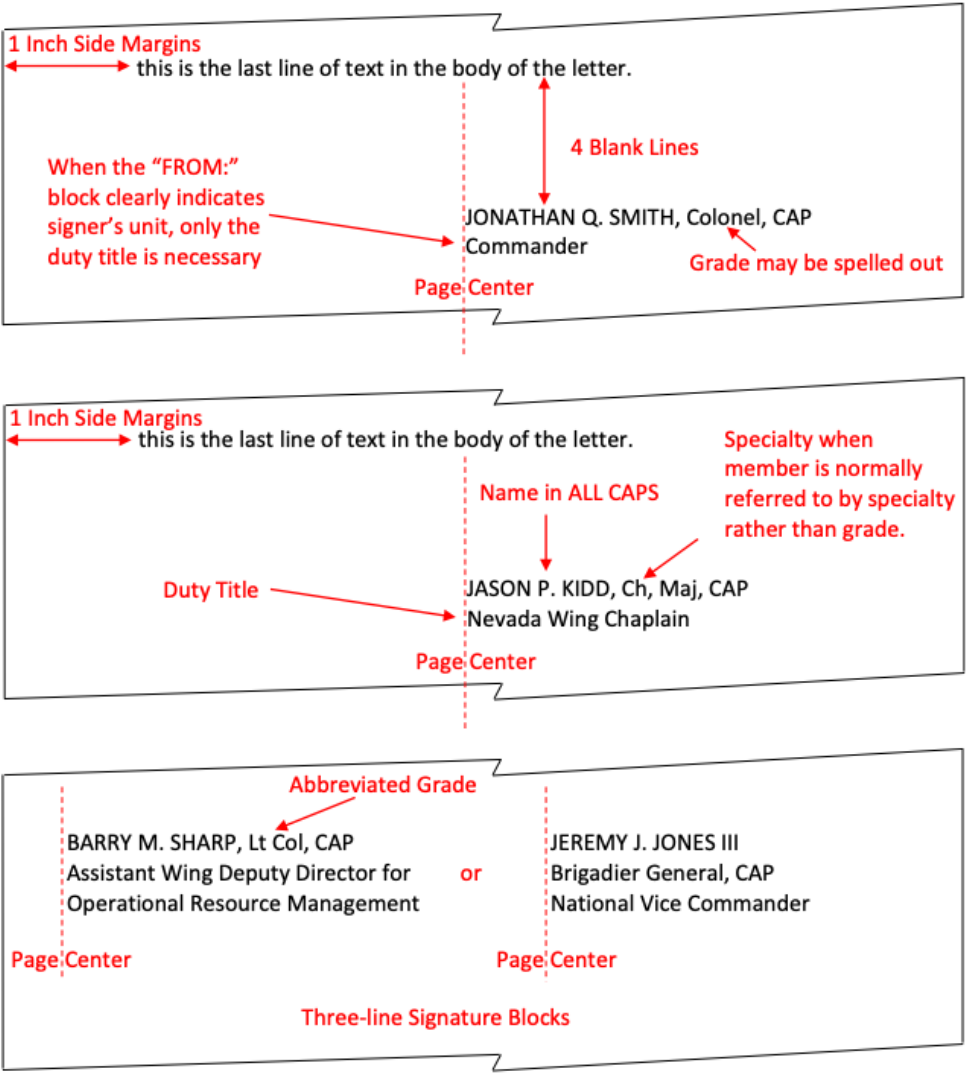

The signature block comes in two standard formats: a two-line and a three-line block.

a. The two-line format is the preferred signature block and consists of the signer’s name in

all capital letters, the signer’s grade in Title Case, and finished with “CAP” on the first

line. The second line states the signer’s duty title in Title Case.

b. The three-line signature block may be used when the name and grade or the duty title

are too long for a two-line format.

In either of the above cases, the grade is normally abbreviated using the standard convention,

such as “Lt Col” or “C/MSgt”. It is permissible to spell out the entire grade if doing so doesn’t

needlessly force a three-line signature block, for example “Major” or “Colonel”. Additionally, if

the “FROM:” block clearly identifies the signer’s unit, for example RMR/CC, it is acceptable to

simply state “Commander” as the duty title in the signature block as opposed to spelling out

“Commander, Rocky Mountain Region”.

There is one exception to the “NAME, Grade, CAP” format. If it is customary to refer to

someone by their specialty instead of their grade, then the specialty is reflected after the

signer’s name. This exception is almost always made for chaplains, but on rare occasions, it

might be seen in signature blocks of medical professionals.

The use of graphics, quotes or phrases are inappropriate for signature blocks.

Here are a few examples of the various signature blocks:

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

27

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

28

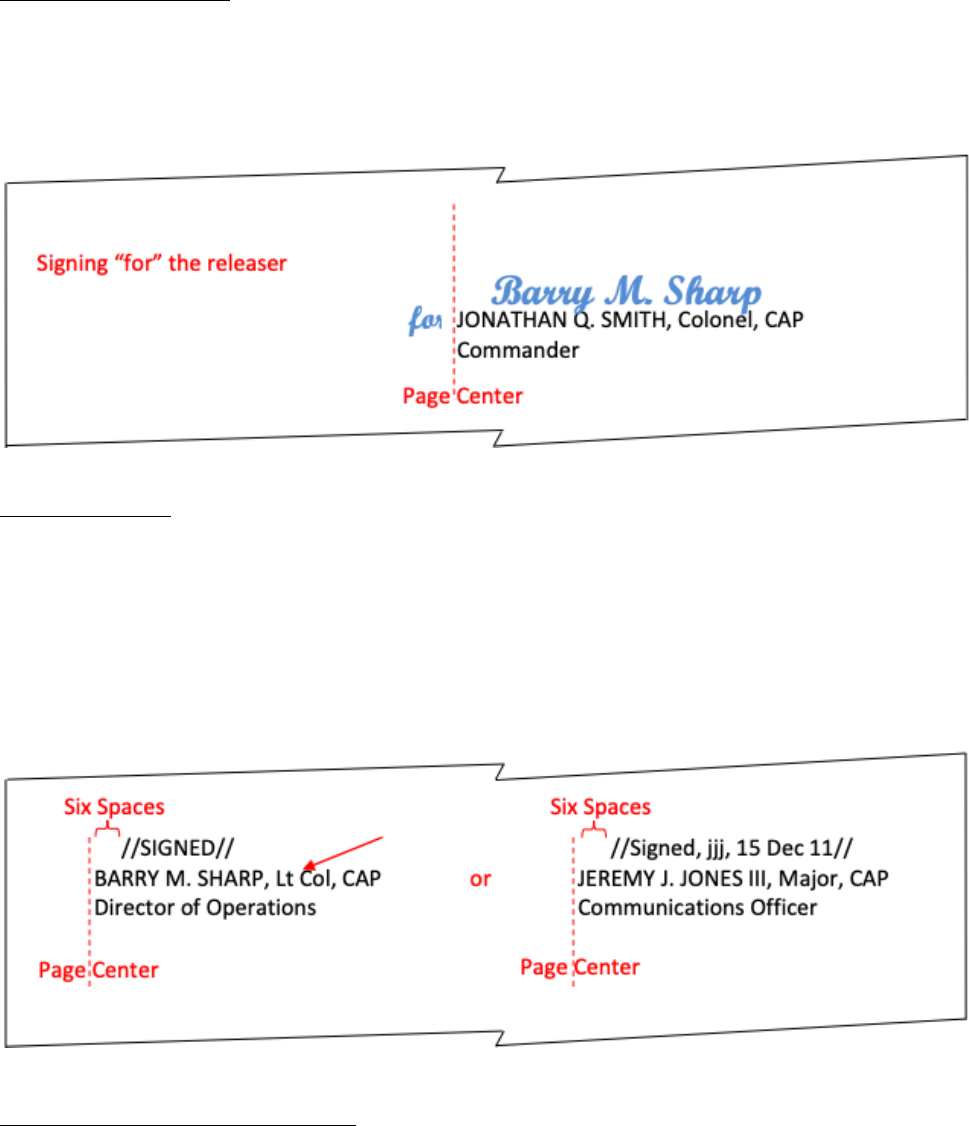

Signing for the Releaser. Occasionally the person who would normally sign the correspondence

is not available to apply his/her signature. In this case, the individual who has temporarily

assumed responsibility for the unavailable individual may sign in that person’s place. In

addition to signing his/her own name, the signer inserts the word “for” just prior to the

intended signer’s printed name. See example below:

Using //SIGNED//. When the correspondence has been approved for release by the signer and

applying a hand-written signature is not feasible, //SIGNED// may be used to indicate that the

correspondence is approved. //SIGNED// may also be used on text copies of correspondence

when the original was signed, and may also be used for signing e-mails. Consider written

correspondence received via e-mail, copied or stamped “//SIGNED//” as authoritative. A

common alternative to //SIGNED// is to include the signer’s initials and date, for example

“//Signed, bms, 15 Dec 11//”. Place the //SIGNED// six spaces to the right of the center of the

page as shown below.

Email Memorandum Signature Block. For memorandum style email, follow the above signature

block guidance; however, instead of beginning the signature block at page center, the closing

element is positioned at the left edge of the document. The use of civilian or personal

signature elements is inappropriate for CAP email correspondence.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

29

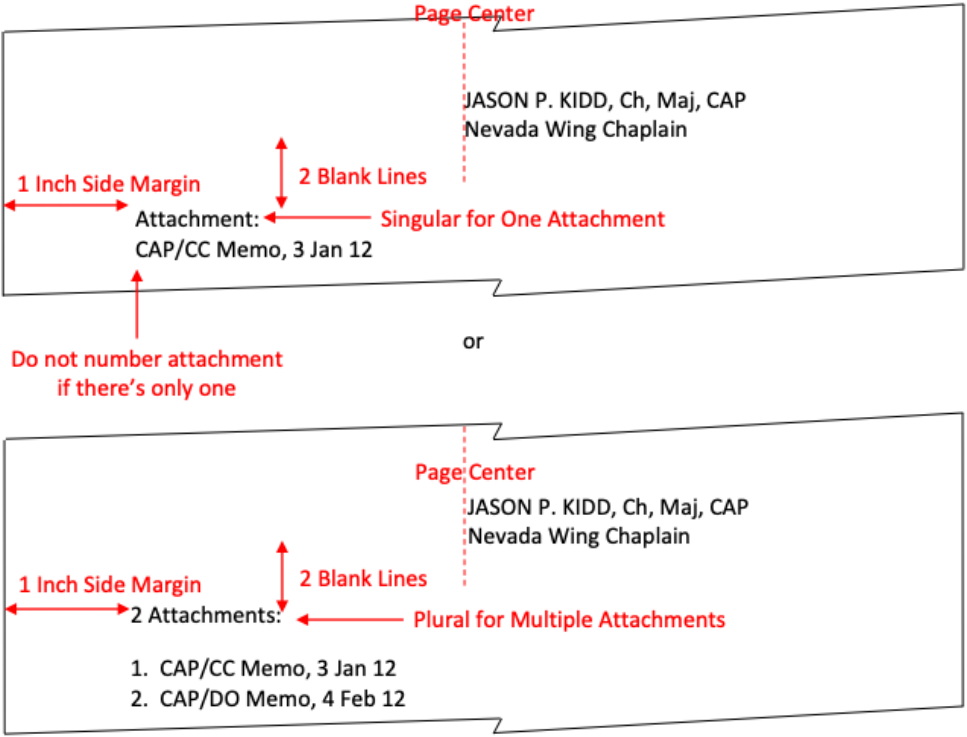

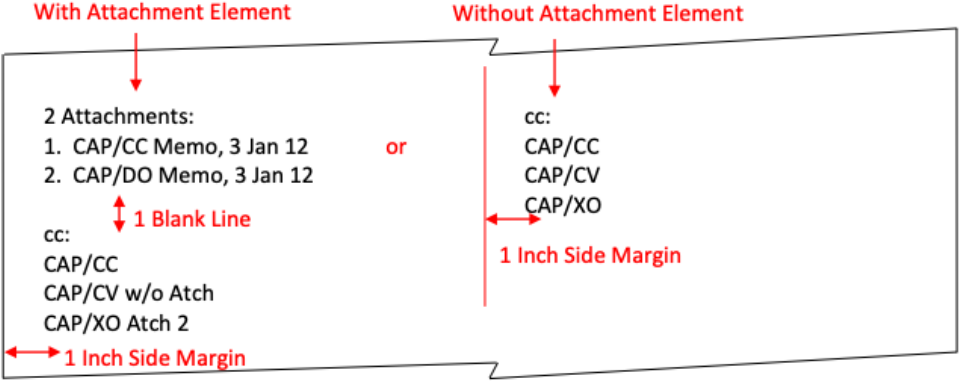

Attachment Element. When attachments accompany the memorandum, type

"Attachment(s):” at the left margin, on the third line below the signature element. If there is

more than one attachment, list each one by number in the order you refer to them in the

memorandum. Describe each attachment briefly. Cite the office or origin, the type of

correspondence and the date. The attachment element should not be split by a page break.

See examples below:

Courtesy Copy Element. If information copies are sent to individuals other than the

addressee(s), type "cc:" at the left margin, on the second line below the attachment element. If

there is no attachment element, type the courtesy listing starting on the third line below the

signature block. List names or organization designations and office symbols of those to receive

copies, one below the other. If a courtesy copy is sent without including the attachment(s),

indicate such by adding "w/o Atch" at the end of the line. For example:

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

30

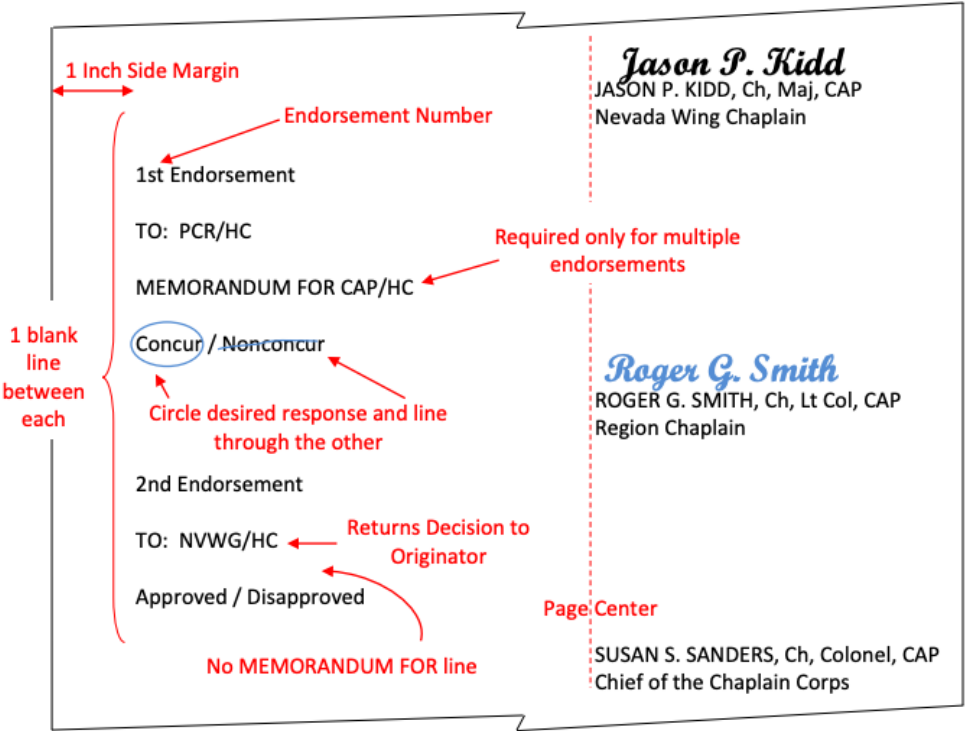

Endorsements. There are times when an originator lacks decision-making authority to initiate

actions outlined in the memorandum. Sometimes the action requires concurrence of others

before the approval authority makes a decision, or perhaps two approvals are required. One

option is to have all parties reply to the originator with their own concurrence/approval letters.

An easier alternative is to use an endorsement statement.

For a hard copy memorandum, endorsements follow the original correspondence, beginning on

the second line below the signature block, attachment element, or courtesy copy element,

whichever is last. The endorsement includes the numerical endorsement, a “TO:” line, a

“MEMORANDUM FOR” line to the next person in the endorsement chain (for multiple

endorsements), and an action line. It is completed with the signature block of the individual

taking the action.

Endorsement statements in a memorandum style email are much simpler. Email endorsements

may be positioned either above or below the original correspondence; however, they are

usually found at the top of the email due to forward/reply ease of emails. There is one

difference too; as mentioned previously, the email endorsement signature block is positioned

at the left edge.

An example of a two-endorsement statement is shown on the next page.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

31

Putting it all together, the memorandum style letter might look like the example on the next

page.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

32

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

33

“Letters are something from you. It’s a

different kind of intention than writing an

email.”

Keanu Reeves

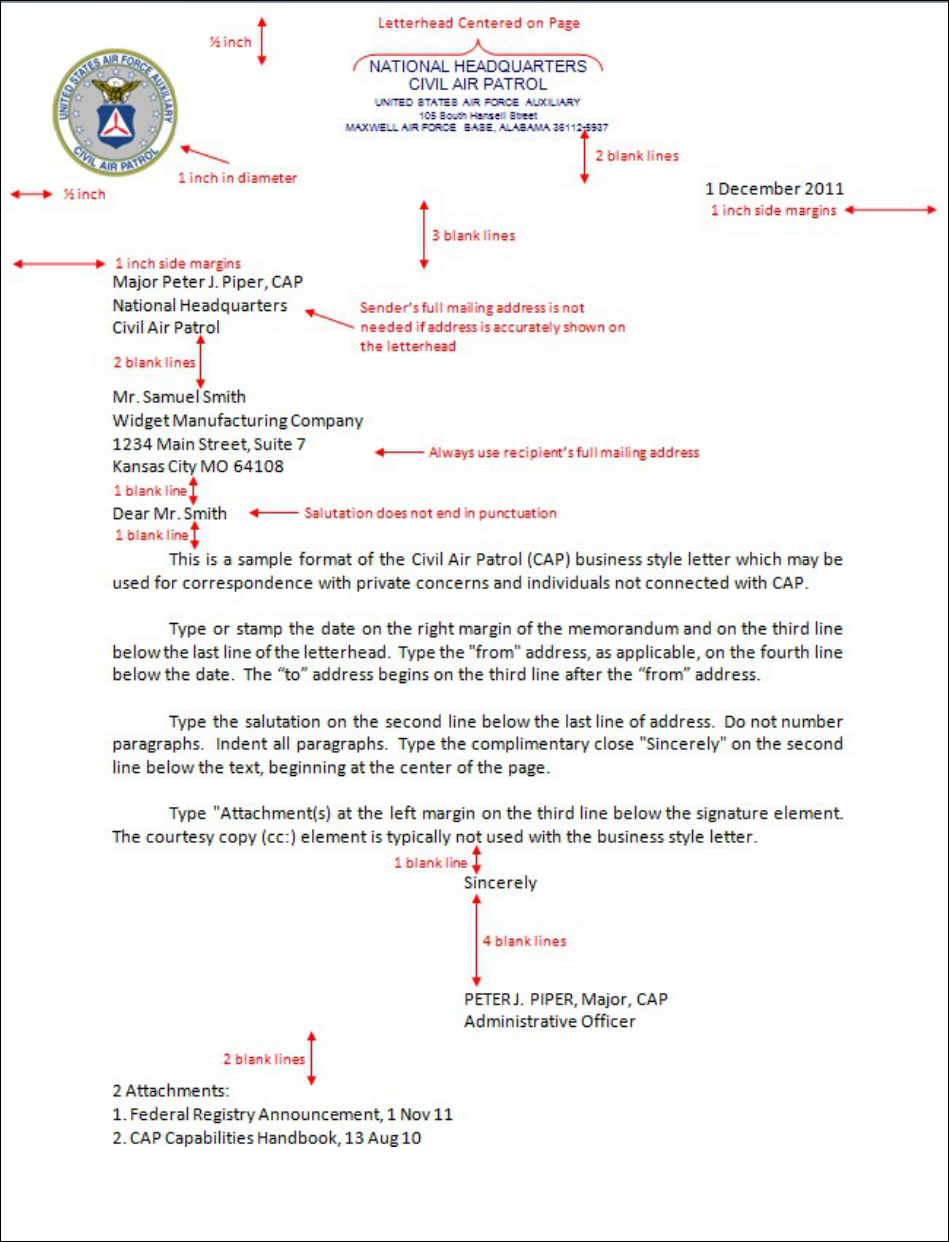

The Business Style Letter

The business style letter is used for correspondence of a private nature, such as a personal

thank you letter, or for recipients of a non-governmental nature, such as a partnership with

another non-profit organization. As such, there is much less structure than the formal

memorandum style letter.

The business style letter may be written on letterhead. Like the memorandum style letter, it

too has a header element, body and closing element; however, some of the other elements are

optional and some are not used. Each of these elements will be discussed in detail.

Aside from the structure, there are several key differences between the business style letter

and the memorandum style letter. These differences are highlighted below.

Element

Business Style Letter

Memorandum Style Letter

Letterhead

Optional

Optional

Heading Element

Date

Return Address

To Address

Salutation

Date

MEMORANDUM FOR

FROM:

SUBJECT:

Body

No paragraph numbers

Paragraphs are indented

Margins are 1 inch on all

sides (unless using

letterhead)

Paragraphs are numbered

Paragraphs are not indented

Margins are 1 inch on all

sides (unless using

letterhead)

Closing Element

Complimentary close,

normally using “Sincerely”

Normal signature block

Normal signature block

Courtesy Copy Element

Normally not used

Optional

Endorsements

Never used

Optional

Email Version

No

Yes

Overall length

Attempt to limit to 1 page

May be multiple pages

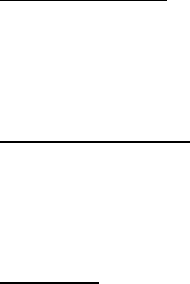

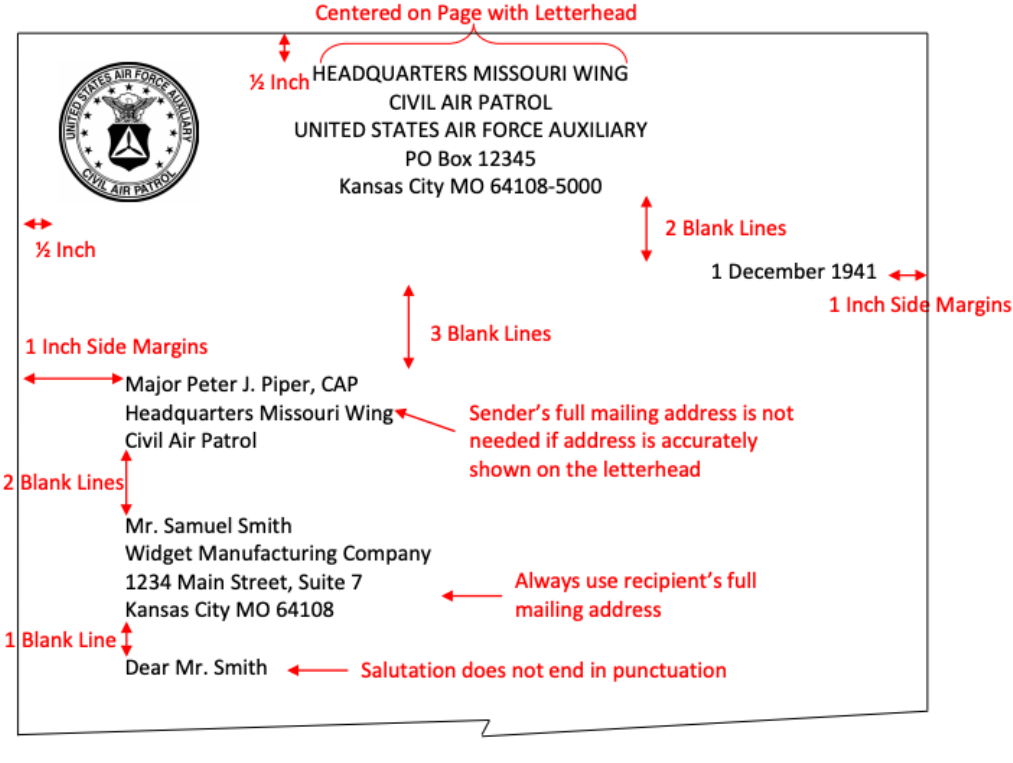

Heading Element. The business style letter heading element includes the date, sender’s

address, recipient’s address and the salutation.

Date. Type or stamp the date on the right margin of the letter and on the third line below the

last line of the letterhead. If letterhead is not used, place the date 1.75 inches (or 10 lines)

from the top edge of the page.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

34

Indicate the date in the format of day, month, and year; for example, 7 Dec 12 or 7 December

2012. As a general rule, when the month is shortened, such as Aug, then the year is shortened

to the last two digits. When the month is spelled out, such as August, the date is completed

with the four-digit year. The date reflects the date the letter is actually signed.

Sender’s Address. If the stationery is not preprinted with the full address of the sender or

sender’s organization, then type the sender’s address using Title Case format. Begin typing the

address at the left margin on the fourth line below the date. Include name, grade and, if not on

letterhead, the complete mailing address of the sender.

Recipient’s Address. The recipient’s address follows the same format as the sender’s. Unlike

the sender’s address where the full address is optional if accurately displayed on letterhead,

the recipient’s address is always provided in full. The recipient’s address begins on the third

line below the sender’s address block.

Salutation. The salutation introduces the body of the letter and begins on the second line

below the recipient’s address block. It is preferred that the sender know the name of the

recipient. In this case, the appropriate salutation takes the form of “Dear Title Last Name”, as

in "Dear Inspector Jones" or "Dear Mr. Brown". If the recipient’s name is not known, an

acceptable salutation is “Dear Sir” or “Dear Ma’am” however doing so presents the sender with

a 50-50 chance of getting the gender correct. A better alternative is to address the letter by

professional or organizational title, such as “Dear Department Head”. In any case, no

punctuation is used at the end of the salutation. Use punctuation after abbreviations such as

"Mr.," "Mrs." and "Dr."; however, no punctuation is used with abbreviated CAP/military grades.

The Tongue and Quill offers an extensive list of addresses, salutations and closures in the

Personal Letter section. For example, using letterhead might appear as shown on the next

page.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

35

An example of the business style letter without letterhead is shown on the next page.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

36

Body. The body makes up the substance of the letter and should get to the point while

providing sufficient information to make sure the reader understands your message. Business

style letters are best presented on one page; however, additional information may be included

as attachments.

Like the memorandum style letter, active voice is preferred; however, some readers may find

the message too direct. Passive voice softens the message, but often requires more words and

could change the tone or clarity of the message. Bottom line – know your audience.

Margins. Standard margins on hard copy letters should be 1 inch from all edges of the paper.

The one exception is letterhead, which is placed ½ inch from the top and sides. The remainder

of the letter is framed with 1-inch margins.

Font. Unlike the memorandum style letter, there is no acceptable email format for the business

style letter. However, an alternative to mailing the letter is to email the letter as an

attachment. Given that sans serif style fonts are more easily viewed on a computer, the

preferred font for business style letters is Calibri, a sans serif style font.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

37

Paragraphing. Start the first paragraph on the second line below the salutation. Each

paragraph should be indented with a blank line between subsequent paragraphs. Do not

number paragraphs.

Single paragraph letters of less than eight lines may be double spaced to prevent an awkward

appearance with a lot of white space. An alternative to double-spacing short letters is to

format the letter in landscape mode, but only type on one half of the page. When printed, the

unused half may be removed. A better alternative is to print on appropriately sized stationary.

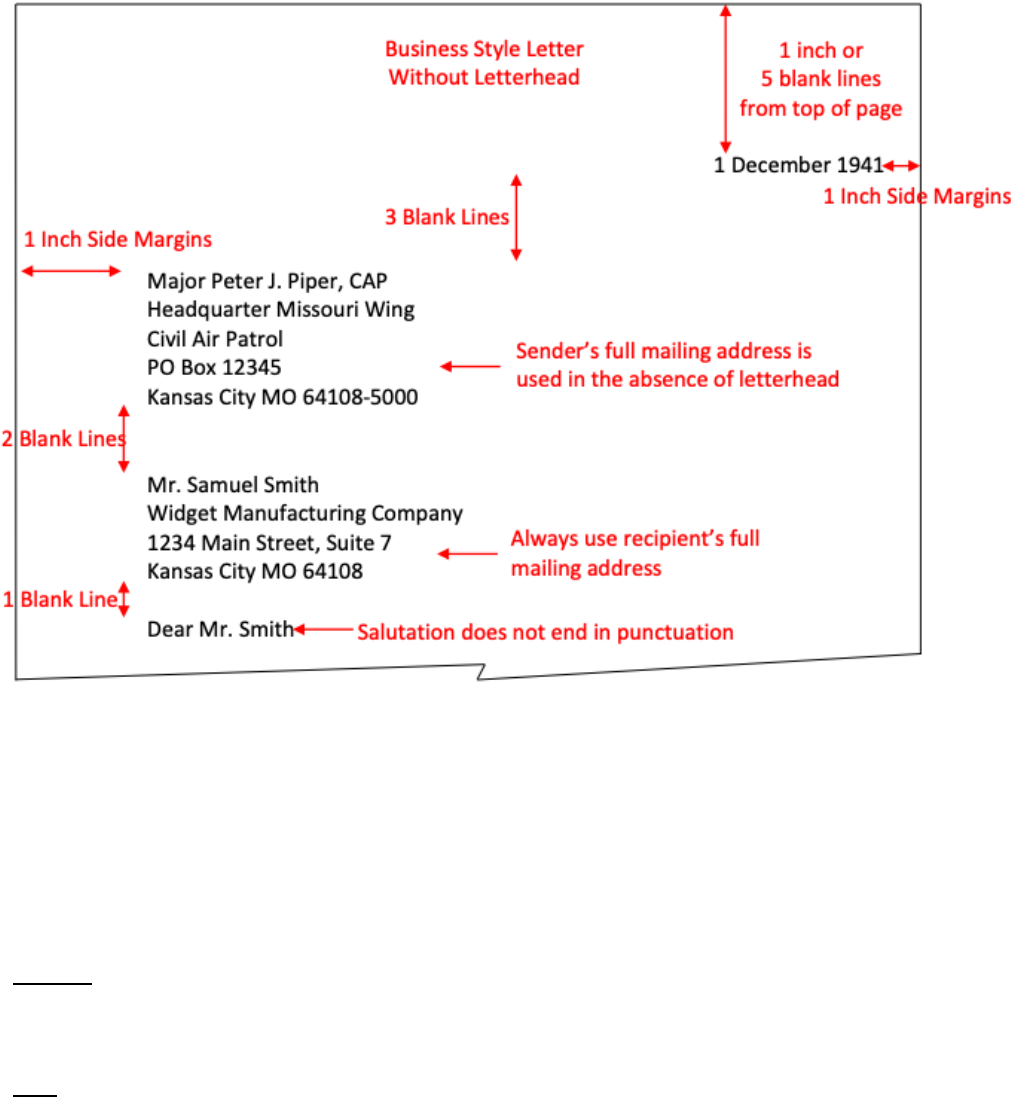

Closing Element. The business style letter closing element is sometimes referred to as the

complimentary close. The accepted convention is to type “Sincerely” starting at page center on

the second line below the last line of the body. There is no punctuation after “Sincerely” and

the standard signature block (see memorandum style letter) begins on the fifth line.

Attachment Element. When attachments accompany the business style letter, type

"Attachment:” at the left margin, on the third line below the signature block. If there is more

than one attachment, list each one by number in the order you refer to them in the letter.

Describe each attachment briefly. Cite the office or origin, the type of correspondence and the

date. The attachment element should not be split by a page break. An example of the closing

and attachment elements looks like this:

Putting it all together, the business style letter might look like the example on the next page.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

38

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

39

“People live too much of their lives

on email or the Internet or text

messages these days. We’re losing

all of our communication skills.”

Tracy Morgan

ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATIONS

Electronic communications are prevalent in the world today and occur in all forms, from a

simple email to social media, online video conferencing, smart phone applications, texts, web

pages, and many more. In fact, there are so many forms of electronic communication that this

topic could have its own publication. Couple that with near daily introduction of new means to

communicate and such a publication would be out of date before it’s even released. With this

in mind, the information below is more of a guide for do’s and don’ts in CAP, and not

necessarily a “how to” manual.

If you’re new to social media, most sites offer a help page to get you started. Additionally,

there are countless other resources available, many of which are free, to assist you in creating

professional emails, web pages and other forms of electronic communication. One such

resource is The Tongue and Quill chapter on Electronic Communication.

Communication is no longer challenged by distance; rather people on opposite sides of the

globe can communicate with the click of a mouse. The ease of electronic communication

presents both benefits and challenges. Probably the greatest benefit is the speed in which a

recipient, to include large audiences, can be reached. On the flip side, and probably worst of

all, never forget that if it’s on the internet, it’s there forever. So care must always be used

when communicating electronically.

Email. In CAP, email is by far the most

frequently used form of electronic

communication to conduct daily business. Not

only does email serve to communicate between

one or multiple recipients, but it also establishes

a record of what was communicated. For actions

requiring approval, this record is vitally

important.

A traditional email can replace or supplement other CAP written correspondence such as the

official memorandum. A memorandum style email may be used if guidelines for a

memorandum style letter are followed. Emails may also be used to send other written

correspondence by adding documents as attachments to the email.

“Social media is the most disruptive form of communication humankind has seen

since the last disruptive form of communications, email.”

Ryan Holmes

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

40

“I do love email. Wherever possible I try to communicate asynchronously. I’m

really good at email.”

Elon Musk

There are a number of factors to consider before using any form of e-mail. Some of the

advantages to using email are: 1) it’s fast; 2) it can get to more people; 3) it’s paperless.

Conversely, the same advantages can prove to be disadvantages: 1) it’s fast…a quickly written

email can fan as many fires as it extinguishes; 2) it can get to more people, some of which the

sender may not desire to be recipients, such as when a copy is forwarded into the wrong hands;

3) it’s paperless and while email does leave an electronic trail, hard drive failures and other

anomalies can make things disappear.

The following are general rules of thumb pertaining to emails and are also applicable to texting

and online postings to social media sites:

a. Repeat after me…never, ever send an email

when you’re mad! While it may be your initial

reflex to a situation, DON’T DO IT. If the situation

is an ugly dog, sleep on it. If it’s still an ugly dog

when you awake, then it’s probably an ugly dog.

Oh, and if it’s truly unprofessional, there are better

ways to handle the situation than a return email.

b. Don’t type using all capital letters. Doing so

comes across as SHOUTING…unless, of course,

that is your intention.

c. Email is essentially a one-way conversation and, unlike verbal communication, there

is no way to insert voice inflection or enunciation into an email. Invariably, the

emotion felt in crafting an email is seldom the same emotion sensed when reading

the email. The same goes for sense of humor. If it’s an important email, ask a

colleague to read it silently before you hit the send button. If your colleague senses

the same emotion or humor as you intended, then the real recipient is likely to

sense the same.

d. Know the difference between “To:”, “Cc:” and “Bcc”.

To: are the recipients you actually want the email to go to; those who need the

information you’re providing or are acting on something in the email.

Cc: are the “guest recipients” for which you’re providing awareness of the

information or action in your email. Don’t expect those in the Cc: line to act on

your email. Likewise don’t get offended if they provide their two cents worth.

“A wise man is superior to any

insults which can be put upon him,

and the best reply to unseemly

behavior is patience and

moderation.”

Moliere

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

41

Let’s face it; you invited them into the conversation. Caution – sometimes

replying to all changes recipients from the Cc: line to the To: line.

Bcc: is a blind courtesy copy. It’s blind because neither the To: or Cc: recipients

know others are receiving the email too. Just because your email program

allows Bcc’ing others it doesn’t mean that you should use the feature. Many

believe such blind copying is unethical and therefore its use is not advised.

Another problem with Bcc’ing is that occasionally the individual Bcc’ed will reply

to all. Guess what – you’re now busted. An acceptable alternative is to forward

the email you just sent (without Bcc’s) to your intended Bcc: recipients.

e. Know the difference between “Reply”

and “Reply to All”. Surprisingly, a large

number of people don’t know the

difference…that or they don’t care if they

generate a lot of unnecessary emails for

others. Oftentimes mass emails are sent

to provide awareness to a large number

of people, not to solicit feedback.

“Reply” goes only to the previous sender. “Reply to All” responds to everyone in the

To: and Cc: lines. There are times when “Reply to All” is appropriate, for example

when coordinating on a project. Bottom line, use care when replying to emails.

f. Read the entire thread before forwarding or replying. A thread is the entire email

including the original and all subsequent forwards and replies. Too many times

something is mentioned lower in the thread that’s inappropriate, unprofessional or

may be considered rude to anyone new added to the thread. You have been

warned! There are two solutions to this problem:

1. Always be professional so you don’t regret something later.

2. Delete all but the germane part of the email and respond only to that portion.

In fact, wise individuals that have learned from the experiences of others, make

it a habit to reply only to the original email.

g. Keep it short…period. Nobody likes to read a novel, especially busy people.

Furthermore, people have a tendency to skip over portions of long emails and

ultimately miss what you’re asking them to do or answer a question that you didn’t

ask simply because you buried the salient points in a tome. Remember the rule:

KISS.

h. Speaking of acronyms and abbreviations, we’re all bad at using them, especially

people who do a lot of texting. The problem is not everyone uses or understands

the same acronyms or abbreviations, even within the same organization. The same

goes for using jargon; use plain language when sending an email outside CAP. If you

“Most people do not listen with

the intent to understand; they

listen with the intent to reply.”

Stephen Covey

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

42

don’t heed these words, the end result is the recipient’s confusion could lead to a

misunderstanding or, worse yet, the recipient takes no action at all L.

i. Which brings up the next topic: smilies, emoticons and emoji. These symbols are

used to insert emotion into an otherwise stoic electronic communication. Smilies

are facial expressions made from typed characters, such as :-) for a smiling face or ;-)

for a wink. Similarly, emoticons are actual characters often used in text messages,

but are also found in certain font styles. Emoticons are shortcuts to display an

emotion (i.e. emotion icon). Examples include J happy faces or L frowns.

Conversely, emoji are pictograms that serve as shortcuts to written text, for example

“how sound for dinner?”

Here are a couple of things to think about when using smilies, emoticons and emoji:

1. Use them sparingly and NEVER in a professional correspondence. While they

may appear cute, they’re certainly not professional. Furthermore, not everyone

understands what these symbols mean and could turn a bad reflection on you.

2. Adding a smilie or emoticon after a rude or unprofessional comment does not

soften the blow. It’s like saying “that dress does a nice job at hiding your belly”

J or “that great looking tie makes your big head look smaller” :-)

j. If you include links in your email, make sure they work. Too many times people have

typed a link for what they thought was a legitimate, professional website only to

have the recipient find themselves facing a web page not suitable for younger

viewers. Yep, mistyping .com for .gov can really work wonders for developing

partnerships!

k. The average member receives a tremendous amount of communications every day,

from emails, to texts and social media announcements. As a professional courtesy

and to improve your chances of a timely response to your sent email, add a

descriptor to the beginning of your subject line. Words such as “ACTION” will get

the recipient’s attention and helps them prioritize over emails that include “INFO” in

the subject. “HOT” may be used; however, this word is often overused and like the

old saying, when everything is hot, nothing is hot!

l. Finally, closing the email with a signature block. Many people like to add quotes or

phrases to their signature blocks. Doing so is considered inappropriate in

professional correspondence. When sending the memorandum style email, use the

signature block detailed on page 26. However, when sending a non-memorandum

email, the signature block follows the standardized form that aligns with CAP’s

branding effort.

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

43

Email Signature Block. As mentioned previously, email is the primary method of

communicating in the conduct of CAP’s daily affairs. With such prevalent use, a standardized

signature block is crucial to CAP’s branding efforts. CAP has developed several standardized

signature blocks, which are available on the CAP Brand Portal at brand.gocivilairpatrol.com.

Social Media. Social media is another powerful form of electronic communication, with the

potential to be both powerfully beneficial and powerfully damaging. Social media is used to

share information, videos, photographs and such, but is never used to conduct CAP official

business.

Social media sites are plentiful with new ones popping up

near daily. Their sphere of influence and reach circles the

globe. Therefore, it’s vitally important that any posting

of a CAP nature be professional, respectful and

present a positive reflection on CAP. Hint –

remember CAP’s Core Values when making CAP-

related posts to social media. Another hint – if it’s on

the internet, it’s there forever!

Each site has their own rules regarding use and

etiquette, usually found on the help page. There are

also many other websites that provide social media

etiquette tips. Trying to list all rules would be exhausting, so

here a just a few pointers to ponder before posting to social media:

CAPP 1-2 01 October 2021

44

“It is better to remain silent at the risk of being thought a fool, than to talk and remove

all doubt of it.”

Maurice Switzer

a. Do you think anyone else besides you will be interested in the post? Yes, we all know

people that like to hear themselves talk…or in this case, post. If you answered “no” to

this question, then you are encouraged to start a blog.

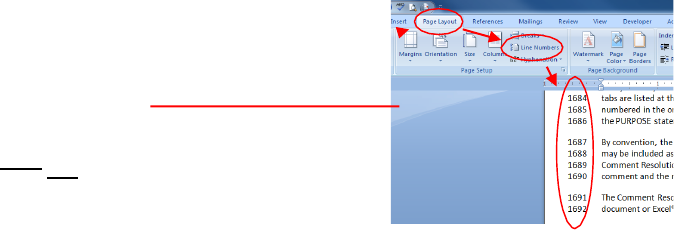

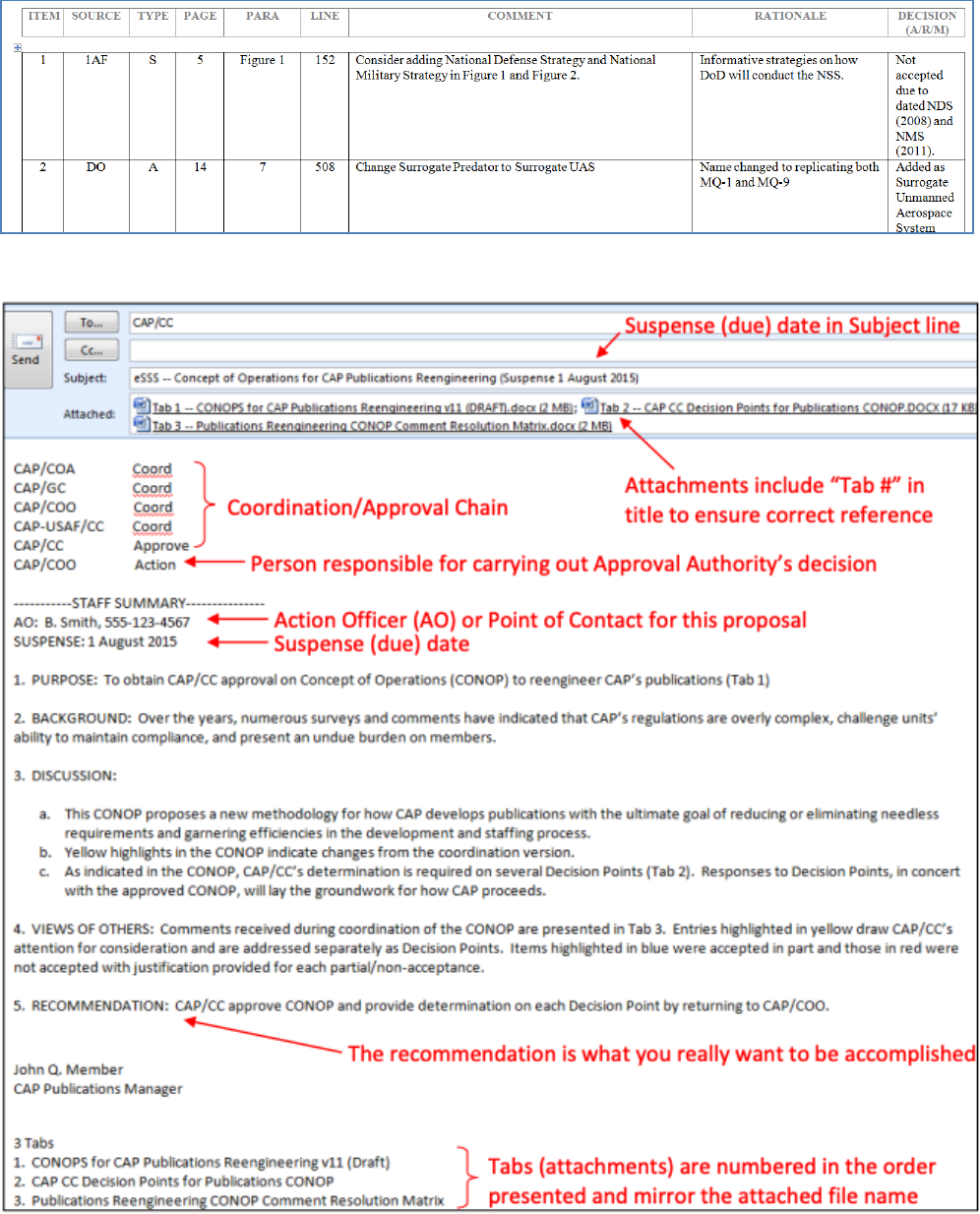

b. Will you intentionally offend someone with your post? Are you hiding behind online