COMMITTEE PRINT

"!

106

TH

C

ONGRESS

2d Session

S. P

RT

.

106–71

TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL

AGREEMENTS: THE ROLE OF THE

UNITED STATES SENATE

A S T U D Y

PREPARED FOR THE

COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS

UNITED STATES SENATE

BY THE

CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

JANUARY 2001

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6012 Sfmt 6012 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS: THE ROLE OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

U

.

S

.

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON

:

1

66–922 CC

COMMITTEE PRINT

"!

106

TH

C

ONGRESS

2d Session

S. P

RT

.

2001

106–71

TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL

AGREEMENTS: THE ROLE OF THE

UNITED STATES SENATE

A S T U D Y

PREPARED FOR THE

COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS

UNITED STATES SENATE

BY THE

CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

JANUARY 2001

Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

(ii)

COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS

JESSE HELMS, North Carolina, Chairman

RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana

CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska

GORDON SMITH, Oregon

ROD GRAMS, Minnesota

SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas

CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming

JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri

BILL FRIST, Tennessee

LINCOLN D. CHAFEE, Rhode Island

JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware

PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland

CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut

JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts

RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin

PAUL WELLSTONE, Minnesota

BARBARA BOXER, California

ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey

S

TEPHEN

B

IEGUN

, Staff Director

E

DWIN

K. H

ALL

, Minority Staff Director

R

ICHARD

J. D

OUGLAS

, Chief Counsel

B

RIAN

M

C

K

EON

, Minority Counsel

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5905 Sfmt 5905 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

(iii)

LETTER OF SUBMITTAL

C

ONGRESSIONAL

R

ESEARCH

S

ERVICE

,

T

HE

L

IBRARY OF

C

ONGRESS

,

Washington, DC, January 2, 2001.

Hon. J

ESSE

H

ELMS

,

Chairman, Committee on Foreign Relations,

U.S. Senate, Washington, DC.

D

EAR

M

R

. C

HAIRMAN

: In accordance with your request, we have

revised and updated the study ‘‘Treaties and Other International

Agreements: The Role of the United States Senate,’’ last published

in 1993. This new edition covers the subject matter through the

106th Congress.

This study summarizes the history of the treatymaking provi-

sions of the Constitution and international and domestic law on

treaties and other international agreements. It traces the process

of making treaties from their negotiation to their entry into force,

implementation, and termination. It examines differences between

treaties and executive agreements as well as procedures for con-

gressional oversight. The report was edited by Richard F.

Grimmett, Specialist in National Defense. Individual chapters were

prepared by policy specialists and attorneys of the Congressional

Research Service identified at the beginning of each chapter.

The Congressional Research Service would like to thank Richard

Douglas, Chief Counsel of the Committee, Edwin K. Hall, Minority

Staff Director of the Committee, Brian P. McKeon, Minority Coun-

sel of the Committee, and Robert Dove, Parliamentarian of the

Senate, for their comments on Senate procedures for consideration

of treaties. We would also like to thank Robert E. Dalton, Assistant

Legal Adviser for Treaty Affairs, Department of State, and other

staff members of the Treaty Office for their assistance with various

factual questions regarding treaties and executive agreements.

Sincerely,

D

ANIEL

P. M

ULHOLLAN

,

Director.

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 6601 Sfmt 6601 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 6601 Sfmt 6601 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

(v)

C O N T E N T S

Page

Letter of submittal ................................................................................................... iii

Introductory note ..................................................................................................... xi

I. Overview of the treaty process ............................................................................ 1

A. Background .................................................................................................. 2

The evolution of the Senate role .............................................................. 2

Treaties under international law ............................................................. 3

Treaties under U.S. law ............................................................................ 4

Executive agreements under U.S. law ..................................................... 4

(1) Congressional-executive agreements .......................................... 5

(2) Agreements pursuant to treaties ................................................. 5

(3) Presidential or sole executive agreements .................................. 5

Steps in the U.S. process of making treaties and executive agree-

ments ...................................................................................................... 6

Negotiation and conclusion ............................................................... 6

Consideration by the Senate ............................................................. 7

Presidential action after Senate action ............................................ 12

Implementation .................................................................................. 12

Modification, extension, suspension, or termination ....................... 13

Congressional oversight ..................................................................... 14

Trends in Senate action on treaties ......................................................... 14

B. Issues in treaties submitted for advice and consent ................................. 15

Request for consent without opportunity for advice ............................... 15

Multilateral treaties .................................................................................. 16

Diminishing use of treaties for major political commitments ............... 17

Unilateral executive branch action to reinterpret, modify, and termi-

nate treaties ........................................................................................... 18

Difficulty in overseeing treaties ............................................................... 19

Minority power .......................................................................................... 19

The House role in treaties ........................................................................ 19

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties ............................................. 20

C. Issues in agreements not submitted to the Senate ................................... 21

Increasing use of executive agreements .................................................. 22

Oversight of executive agreements—the Case-Zablocki Act .................. 22

Learning of executive agreements ........................................................... 22

Determining authority for executive agreements ................................... 23

Non-binding international agreements .................................................... 23

D. Deciding between treaties and executive agreements .............................. 24

Scope of the treaty power; proper subject matter for treaties ............... 24

Scope of executive agreements; proper subject matter for executive

agreements ............................................................................................. 25

Criteria for treaty form ............................................................................. 26

II. Historical background and growth of international agreements .................... 27

A. Historical background of constitutional provisions ................................... 27

The Constitutional Convention ................................................................ 28

Debate on adoption .................................................................................... 29

B. Evolution into current practice ................................................................... 31

Washington’s administrations .................................................................. 32

Presidencies from Adams to Polk ............................................................. 35

Indian treaties ........................................................................................... 36

Conflicts and cooperation .......................................................................... 37

Executive agreements and multilateral agreements .............................. 38

Increasing proportion of executive and statutory agreements .............. 40

Growth in multilateral agreements ......................................................... 42

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00007 Fmt 5905 Sfmt 5905 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

Page

vi

III. International agreements and international law ........................................... 43

A. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties ....................................... 43

International law status ........................................................................... 43

Senate action on the convention .............................................................. 45

B. Treaty definition .......................................................................................... 49

C. Criteria for a binding international agreement ........................................ 50

Intention of the parties to be bound under international law ............... 50

Significance ................................................................................................ 51

Specificity ................................................................................................... 52

Form of the agreement ............................................................................. 52

D. Limitations on binding international agreements and grounds for in-

validation ....................................................................................................... 53

Invalidation by fraud, corruption, coercion or error ............................... 53

Invalidation by conflict with a peremptory norm of general inter-

national law (jus cogens) ....................................................................... 54

Invalidation by violation of domestic law governing treaties ................ 56

E. Non-binding agreements and functional equivalents ............................... 58

Unilateral commitments and declarations of intent ............................... 59

Joint communiques and joint statements ............................................... 60

Informal agreements ................................................................................. 61

Status of non-binding agreements ........................................................... 62

IV. International agreements and U.S. law .......................................................... 65

A. Treaties ......................................................................................................... 65

Scope of the treaty power ......................................................................... 65

Treaties as law of the land ....................................................................... 72

B. Executive agreements .................................................................................. 76

Congressional-executive agreements ....................................................... 78

Agreements pursuant to treaties ............................................................. 86

Presidential or sole executive agreements .............................................. 87

V. Negotiation and conclusion of international agreements ................................ 97

A. Negotiation ................................................................................................... 97

Logan Act ................................................................................................... 98

B. Initiative for an agreement; setting objectives .......................................... 100

C. Advice and consent on appointments ......................................................... 103

Unconfirmed presidential agents ............................................................. 105

D. Consultations during the negotiations ....................................................... 106

Inclusion of Members of Congress on delegations .................................. 109

E. Conclusion or signing .................................................................................. 111

F. Renegotiation of a treaty following Senate action ..................................... 112

G. Interim between signing and entry into force; provisional application .. 113

VI. Senate consideration of treaties ....................................................................... 117

A. Senate receipt and referral ......................................................................... 118

Senate Rule XXX ....................................................................................... 118

Executive session—proceedings on treaties ............................................ 119

Action on receipt of treaty from the president ........................................ 119

B. Foreign Relations Committee consideration .............................................. 122

C. Conditional approval ................................................................................... 124

Types of conditions .................................................................................... 124

Condition regarding treaty interpretation .............................................. 128

Condition regarding supremacy of the Constitution .............................. 131

D. Resolution of ratification ............................................................................. 136

E. Senate floor procedure ................................................................................. 136

Executive session ....................................................................................... 136

Non-controversial treaties ........................................................................ 137

Controversial treaties ............................................................................... 138

Consideration of treaties under cloture ................................................... 141

Final vote ................................................................................................... 142

Failure to receive two-thirds majority ..................................................... 143

F. Return or withdrawal .................................................................................. 145

VII. Presidential options on treaties after Senate action ..................................... 147

A. Ratification ................................................................................................... 147

Ratification of the treaty .......................................................................... 147

Exchange or deposit of instruments of ratification (entry into force) ... 149

B. Resubmission of the treaty or submission of protocol .............................. 150

C. Inaction or refusal to ratify ......................................................................... 152

Procedure when other nations attach new conditions ............................ 153

VIII. Dispute settlement, rules of interpretation, and obligation to implement 157

A. Dispute settlement ...................................................................................... 157

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00008 Fmt 5905 Sfmt 5905 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

Page

vii

VIII. Dispute settlement, rules of interpretation, and obligation to imple-

ment—Continued

A. Dispute settlement—Continued

Conciliation ................................................................................................ 158

Arbitration ................................................................................................. 159

Judicial settlement .................................................................................... 161

B. Rules of interpretation ................................................................................ 163

C. Obligation to implement .............................................................................. 166

IX. Amendment or modification, extension, suspension, and termination of

treaties and other international agreements ..................................................... 171

A. Introduction .................................................................................................. 171

B. Amendment and modification ..................................................................... 176

Treaties ...................................................................................................... 176

Executive agreements ............................................................................... 183

C. Extension ...................................................................................................... 184

Treaties ...................................................................................................... 184

Executive agreements ............................................................................... 187

D. Suspension ................................................................................................... 187

Treaties ...................................................................................................... 187

Executive agreements ............................................................................... 192

E. Termination or withdrawal ......................................................................... 192

Treaties ...................................................................................................... 192

Terms of treaty; unanimous consent ................................................ 192

Breach ................................................................................................. 193

Impossibility of performance ............................................................. 194

Rebus sic stantibus ............................................................................. 194

Jus cogens ........................................................................................... 195

Severance of diplomatic relations ..................................................... 195

Hostilities ............................................................................................ 196

State succession .................................................................................. 196

F. U.S. law and practice in terminating international agreements ............. 198

General ....................................................................................................... 198

Treaties ...................................................................................................... 201

Executive action pursuant to prior authorization or direction by

the Congress ................................................................................... 202

Executive action pursuant to prior authorization or direction by

the Senate ....................................................................................... 204

Executive action without prior specific authorization or direction,

but with subsequent approval by the Congress ........................... 205

Executive action without specific prior authorization or direction,

but with subsequent approval by the Senate ............................... 205

Executive action without specific prior authorization or direction,

and without subsequent approval by either the Congress or

the Senate ....................................................................................... 206

Executive agreements ............................................................................... 208

X. Congressional oversight of international agreements ...................................... 209

A. The Case Act ................................................................................................ 209

Origins ........................................................................................................ 210

Provisions for publication .................................................................. 210

The Bricker amendment and its legacy ........................................... 212

National commitments concerns ....................................................... 213

Military base agreements (Spain, Portugal, Bahrain) .................... 215

Separation of Powers Subcommittee approach ................................ 216

Intent and content of the Case Act .......................................................... 217

Implementation, 1972–1976 ..................................................................... 218

Amendments of the Case Act, 1977–1978 ............................................... 222

Committee procedures under the Case Act ............................................. 224

Senate Foreign Relations Committee procedures ............................ 224

House International Relations Committee procedures ................... 225

Impact and assessment of the Case Act .................................................. 225

Number of agreements transmitted ................................................. 226

Late transmittal of Case Act agreements ........................................ 228

Insufficient transmittal of agreements to Congress ........................ 230

Pre-Case Act executive agreements .................................................. 232

B. Consultations on form of agreement .......................................................... 233

C. Congressional review or approval of agreements ...................................... 235

D. Required reports to Congress ..................................................................... 238

E. Other tools of congressional oversight ....................................................... 239

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00009 Fmt 5905 Sfmt 5905 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

Page

viii

X. Congressional oversight of international agreements—Continued

E. Other tools of congressional oversight—Continued

Implementation legislation ....................................................................... 240

Recommendations in legislation ............................................................... 240

Consultation requirements ....................................................................... 242

Oversight hearings .................................................................................... 243

XI. Trends in major categories of treaties ............................................................. 245

A. Political and security agreements .............................................................. 246

National security and defense commitments .......................................... 247

Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany ............. 250

Maritime Boundary Agreement with the Soviet Union .................. 251

Arms control treaties ................................................................................ 251

INF Treaty .......................................................................................... 254

Threshold Test Ban Treaty and Protocol ......................................... 256

CFE Treaty ......................................................................................... 257

CFE Flank Agreement ....................................................................... 257

START I Treaty .................................................................................. 258

START II ............................................................................................. 260

Open Skies Treaty .............................................................................. 261

Chemical Weapons Convention ......................................................... 261

Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty ...................................................... 262

B. Economic treaties ......................................................................................... 265

Friendship, commerce, and navigation treaties ...................................... 265

Investment treaties ................................................................................... 266

Consular conventions ................................................................................ 269

Tax conventions ......................................................................................... 270

Treaty shopping .................................................................................. 271

Exchange of information .................................................................... 272

Allocation of income of multinational business enterprises ........... 272

Taxation of equipment rentals .......................................................... 272

Arbitration of competent authority issues ....................................... 272

Insurance excise tax ........................................................................... 273

C. Environmental treaties ............................................................................... 273

No-reservations clauses ............................................................................ 274

Fishery conventions .................................................................................. 276

D. Legal cooperation ......................................................................................... 278

Extradition treaties ................................................................................... 278

Mutual legal assistance treaties .............................................................. 282

E. Human rights conventions .......................................................................... 285

Genocide Convention ................................................................................. 287

Labor conventions ..................................................................................... 288

Convention Against Torture ..................................................................... 290

Civil and Political Rights Covenant ......................................................... 291

Racial Discrimination Convention ........................................................... 292

Other human rights treaties .................................................................... 293

A

PPENDIXES

1. Treaties and other international agreements: an annotated bibliography ..... 295

A. Introduction .................................................................................................. 295

B. International agreements and international law ...................................... 295

1. Overview ................................................................................................ 295

a. General ........................................................................................... 295

b. Treaties and agreements involving international organiza-

tions ................................................................................................. 298

2. Negotiation and conclusion of treaties and international agree-

ments ...................................................................................................... 299

a. Negotiation and the treatymaking process .................................. 299

(1) General ................................................................................... 299

(2) Multilateral treaties .............................................................. 299

b. Amendments, interpretive declarations, and reservations ......... 300

c. Acceptance, depositary, registration and publication .................. 301

(1) Acceptance .............................................................................. 301

(2) Depositary .............................................................................. 301

(3) Registration and publication ................................................ 302

3. Entry into force ..................................................................................... 302

4. Interpretation ........................................................................................ 303

5. Modification, suspension, and termination of treaties ....................... 307

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00010 Fmt 5905 Sfmt 5905 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

Page

ix

1. Treaties and other international agreements—Continued

B. International agreements and international law —Continued

5. Modification, suspension, and termination of treaties —Continued

a. Overview .........................................................................................

307

b. Questions of treaty validity ...........................................................

310

6. Dispute settlement ................................................................................

312

7. Succession of states ...............................................................................

313

C. International agreements and U.S. law .....................................................

314

1. General ...................................................................................................

314

2. Congressional and Presidential roles in the making of treaties

and international agreements ...............................................................

319

3. Communication of international agreements to Congress .................

330

4. U.S. termination of treaties ..................................................................

332

D. Guides ...........................................................................................................

334

1. Guides to resources on treaties ............................................................

334

2. Compilations of treaties, and indexes international in scope ............

335

3. U.S. treaties and the treatymaking process .......................................

338

a. Sources for treaty information throughout the treatymaking

process .............................................................................................

338

CIS/index .....................................................................................

338

Congressional Index ....................................................................

338

Congressional Record ..................................................................

341

Executive Journal of the Senate ................................................

341

Senate executive reports ............................................................

341

Senate Foreign Relations Committee calendar ........................

341

Senate treaty documents ............................................................

341

Department of State Dispatch ...................................................

341

Department of State Bulletin ....................................................

341

Foreign Policy Bulletin ...............................................................

342

Department of State Press Releases .........................................

342

Federal Register ..........................................................................

342

Monthly Catalog ..........................................................................

342

Shepard’s United States Citations—Statutes Edition .............

342

Statutes at Large ........................................................................

342

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents ......................

343

b. Official treaty series ......................................................................

343

TIAS .............................................................................................

343

UST ..............................................................................................

343

c. Indexes and retrospective compilations ........................................

343

Current ........................................................................................

343

1950+ ............................................................................................

344

1776–1949 ....................................................................................

344

1776–1949 (Bevans) ....................................................................

344

1776–1931 (Malloy) .....................................................................

344

1776–1863 (Miller) ......................................................................

344

d. Status of treaties ............................................................................

345

Treaties in force ..........................................................................

345

Unperfected treaties ...................................................................

345

Additional information ...............................................................

345

4. Topical collections .................................................................................

346

a. Diplomatic and national security issues ......................................

346

b. Economic and commercial issues ..................................................

347

c. International environmental issues and management of com-

mon areas ........................................................................................

348

2. Case-Zablocki Act on Transmittal of International Agreements and Related

Reporting Requirements ......................................................................................

349

3. Coordination and reporting of international agreements, State Department

regulations ............................................................................................................

351

4. Department of State Circular 175 Procedures on Treaties ..............................

357

710 Purpose and disclaimer .............................................................................

357

711 Purpose (state only) ...................................................................................

357

712 Disclaimer (state only) ..............................................................................

357

720 Negotiation and signature ........................................................................

357

721 Exercise of the international agreement power ......................................

358

722 Action required in negotiation and/or signature of treaties and agree-

ments .............................................................................................................

359

723 Responsibility of office or officer conducting negotiations .....................

361

724 Transmission of international agreements other than treaties to Con-

gress: compliance with the Case-Zablocki Act ............................................

364

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00011 Fmt 5905 Sfmt 5905 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

Page

x

4. Department of State Circular 175 Procedures on Treaties—Continued

725 Publication of treaties and other international agreements of the

United States ................................................................................................ 364

730 Guidelines for concluding international agreements .............................. 364

731 Conformity of texts .................................................................................... 366

732 Exchange or exhibition of full powers ..................................................... 366

733 Signature and sealing ............................................................................... 366

734 Exchange of ratifications .......................................................................... 367

740 Multilateral treaties and agreements ...................................................... 367

741 Official and working languages ................................................................ 368

742 Engrossing ................................................................................................. 369

743 Full powers ................................................................................................ 370

744 Signature and sealing ............................................................................... 370

745 Disposition of final documents of conference .......................................... 370

746 Procedure following signature .................................................................. 371

750 Responsibilities of the Assistant Legal Adviser for Treaty Affairs ....... 371

5. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Senate Ex. L, 92d Congress

1st Session, with list of signatures, ratifications and accessions deposited

as of December 11, 2000 ...................................................................................... 375

Letter of transmittal ........................................................................................ 377

Letter of submittal ........................................................................................... 378

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties .................................................... 384

List of signatures, ratifications deposited and accessions deposited as

of December 11, 2000 .................................................................................... 407

6. Glossary of treaty terminology ........................................................................... 411

7. Simultaneous consideration of treaties and amending protocols .................... 415

1. Treaty with Mexico Relating to Utilization of the Waters of Certain

Rivers (Ex. A, 78–2, and Ex. H, 78–2) ........................................................ 415

2. Convention Between France and the United States as to Double Tax-

ation and Fiscal Assistance and Supplementary Protocol (S. Ex. A,

80–1 and S. Ex. G, 80–2) .............................................................................. 415

3. Tax Convention with Canada and Two Protocols (Ex. T, 96–2; Treaty

Doc. 98–7; and Treaty Doc. 98–22) .............................................................. 416

4. Treaties with the U.S.S.R. on the Limitation of Underground Nuclear

Weapon Tests and on Underground Nuclear Explosions for Peaceful

Purposes and Protocols (Ex. N, 94–2; and Treaty Doc. 101–19) ............... 416

8. Treaties approved by the Senate ........................................................................ 417

2000 ................................................................................................................... 417

1999 ................................................................................................................... 420

1998 ................................................................................................................... 422

1997 ................................................................................................................... 425

1996 ................................................................................................................... 426

1995 ................................................................................................................... 429

1994 ................................................................................................................... 430

1993 ................................................................................................................... 430

9. Treaties rejected by the Senate .......................................................................... 433

1999 ................................................................................................................... 433

10. Letter of response from Acting Director Thomas Graham, Jr. to Senator

Pell accepting the narrow interpretation of the ABM Treaty ..........................

T

ABLES

II–1. Treaties and executive agreements concluded by the United States,

1789–1989 ............................................................................................................. 39

II–2. Treaties and executive agreements concluded by the United States,

1930–1999 ............................................................................................................. 39

X–1. Transmittal of executive agreements to Congress, 1978–1999 ................... 226

X–2. Agencies submitting agreements late, 1979–1999 ....................................... 229

X–3. Statutory requirements for transmittal of agreements to Congress ........... 236

X–4. Required reports related to international agreements ................................ 239

X–5. Legislation implementing treaties ................................................................. 241

XI–1. Human rights treaties pending on the Senate Foreign Relations Com-

mittee calendar ..................................................................................................... 286

A1–1. Publications providing information on U.S. treaties throughout the

treatymaking process ..........................................................................................

C

HARTS

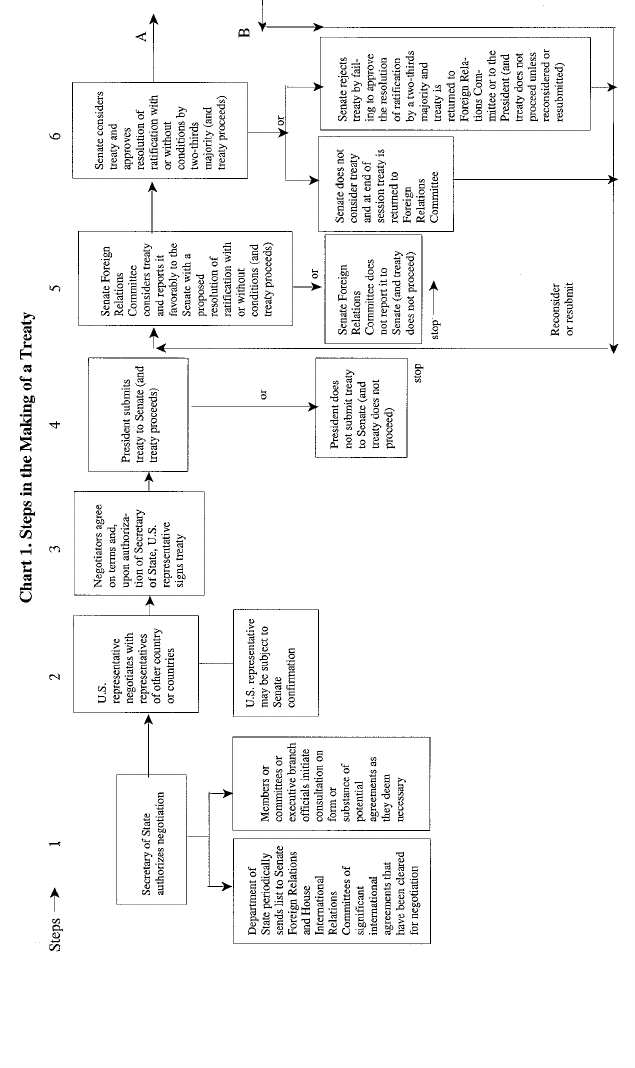

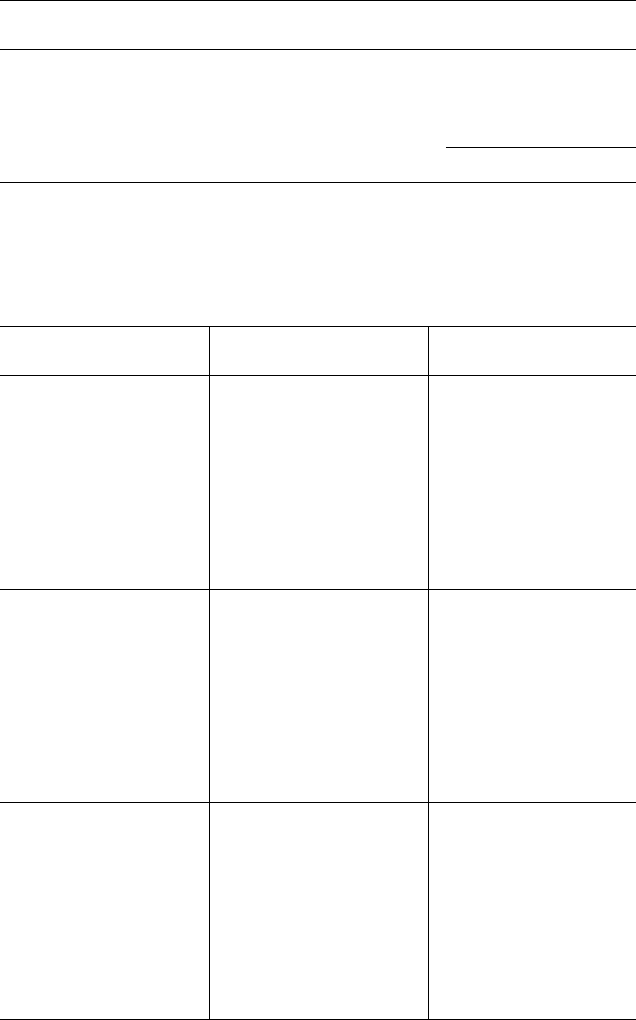

1. Steps in the making of a treaty .......................................................................... 8

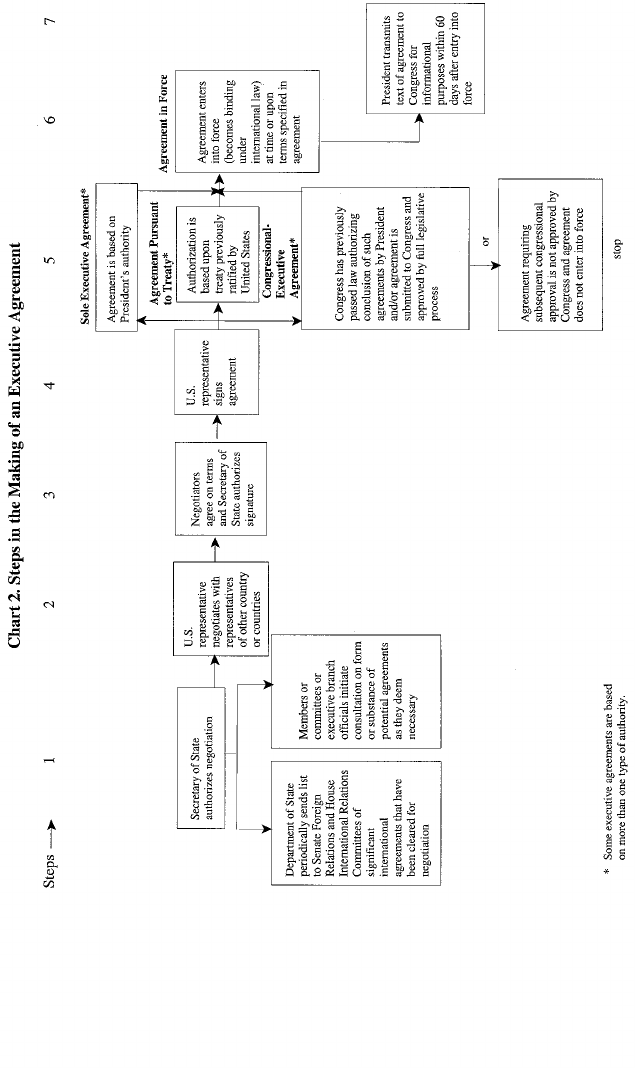

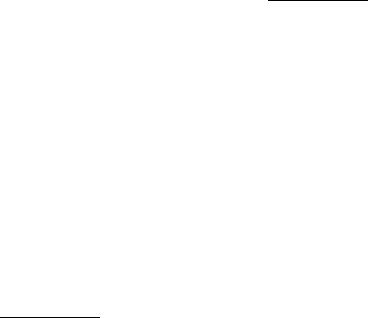

2. Steps in the making of an executive agreement ............................................... 10

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00012 Fmt 5905 Sfmt 5905 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

(xi)

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

This study revises a report bearing the same title published in

1993. It is intended to provide a reference volume for use by the

U.S. Senate in its work of advising and consenting to treaties. It

summarizes international and U.S. law on treaties and other inter-

national agreements. It traces the process of making treaties

through the various stages from their initiation and negotiation to

ratification, entry into force, implementation and oversight, modi-

fication or termination—describing the respective senatorial and

Presidential roles at each stage. The study also provides back-

ground information on issues concerning the Senate role in treaties

and other international agreements through specialized discussions

in individual chapters. The appendix contains, among other things,

a glossary of frequently used terms, important documents related

to treaties: the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (unrati-

fied by the United States); State Department Circular 175 describ-

ing treaty procedures in the executive branch; the State Depart-

ment regulation, ‘‘Coordination and Reporting of International

Agreements,’’ and material related to the Case-Zablocki Act on the

reporting of international agreements to Congress. Also included

are a list of treaties approved by the Senate from January 1993

through October 2000, examples of treaty documents, and an anno-

tated bibliography.

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00013 Fmt 6601 Sfmt 6601 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

(1)

1

Prepared by Richard F. Grimmett, Specialist in National Defense.

I. OVERVIEW OF THE TREATY PROCESS

1

Treaties are a serious legal undertaking both in international

and domestic law. Internationally, once in force, treaties are bind-

ing on the parties and become part of international law. Domesti-

cally, treaties to which the United States is a party are equivalent

in status to Federal legislation, forming part of what the Constitu-

tion calls ‘‘the supreme Law of the Land.’’

However, the word treaty does not have the same meaning in the

United States and in international law. Under international law, a

‘‘treaty’’ is any legally binding agreement between nations. In the

United States, the word treaty is reserved for an agreement that

is made ‘‘by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate’’ (Arti-

cle II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Constitution). International agree-

ments not submitted to the Senate are known as ‘‘executive agree-

ments’’ in the United States, but they are considered treaties and

therefore binding under international law.

For various reasons, Presidents have increasingly concluded ex-

ecutive agreements. Many agreements are previously authorized or

specifically approved by legislation, and such ‘‘congressional-

executive’’ or statutory agreements have been treated almost inter-

changeably with treaties in several important court cases. Others,

often referred to as ‘‘sole executive agreements,’’ are made pursu-

ant to inherent powers claimed by the President under Article II

of the Constitution. Neither the Senate nor the Congress as a

whole is involved in concluding sole executive agreements, and

their status in domestic law is not fully resolved.

Questions on the use of treaties, congressional-executive agree-

ments, and sole executive agreements underlie many issues. There-

fore, any study of the Senate role in treaties must also deal with

executive agreements. Moreover, the President, the Senate, and the

House of Representatives have different institutional interests at

stake, a fact which periodically creates controversy. Nonetheless,

the President, Senate, and House share a common interest in mak-

ing international agreements that are in the national interest in

the most effective and efficient manner possible.

The requirement for the Senate’s advice and consent gives the

Senate a check over all international agreements submitted to it as

treaties. The Senate may refuse to give its approval to a treaty or

do so only with specified conditions, reservations, or understand-

ings. In addition, the knowledge that a treaty must be approved by

a two-thirds majority in the Senate may influence the content of

the document before it is submitted. Even so, the Senate has found

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00014 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

2

2

See Chapters II and VI for references and additional discussion.

it must be vigilant if it wishes to maintain a meaningful role in

treaties that are submitted.

The main threat of erosion of the Senate treaty power comes not

from the international agreements that are submitted as treaties,

however, but from the many international agreements that are not

submitted for its consent. In addition to concluding hundreds of ex-

ecutive agreements, Presidents have made important commitments

that they considered politically binding but not legally binding.

Maintaining the Senate role in treaties requires overseeing all

international agreements to assure that agreements that should be

treaties are submitted to the Senate.

A. B

ACKGROUND

THE EVOLUTION OF THE SENATE ROLE

2

The Constitution states that the President ‘‘shall have Power, by

and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties,

provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur.’’ The Conven-

tion that drafted the Constitution did not spell out more precisely

what role it intended for the Senate in the treatymaking process.

Most evidence suggests that it intended the sharing of the treaty

power to begin early, with the Senate helping to formulate instruc-

tions to negotiators and acting as a council of advisers to the Presi-

dent during the negotiations, as well as approving each treaty en-

tered into by the United States. The function of the Senate was

both to protect the rights of the states and to serve as a check

against the President’s taking excessive or undesirable actions

through treaties. The Presidential function in turn was to provide

unity and efficiency in treatymaking and to represent the national

interest as a whole.

The treaty clause of the Constitution does not contain the word

ratification, which refers to the formal act by which a nation af-

firms its willingness to be bound by a specific treaty. From the be-

ginning, the formal act of ratification has been performed by the

President acting ‘‘by and with the advice and consent of the Sen-

ate.’’ The President ratifies the treaty, but, only after receiving the

advice and consent of the Senate.

When the Constitution was drafted, the ratification of a treaty

was generally considered obligatory by the nations entering into it

if the negotiators stayed within their instructions. Therefore Sen-

ate participation during the negotiations stage seemed essential if

the Senate was to play a meaningful constitutional role. At the

time, such direct participation by the Senate also seemed feasible,

since the number of treaties was not expected to be large and the

original Senate contained only 26 Members.

Within several years, however, problems were encountered in

treatymaking and Presidents abandoned the practice of regularly

getting the Senate’s advice and consent on detailed questions prior

to negotiations. Instead, Presidents began to submit the completed

treaty after its conclusion. Since the Senate had to be able to ad-

vise changes or deny consent altogether if its role was to be mean-

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00015 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

3

3

These include treaties on income taxation with Thailand, signed March 1965, and Brazil,

signed March 13, 1967.

4

Treaty on General Relations with Turkey, January 18, 1927; St. Lawrence Waterway Treaty

with Canada, July 18, 1932 (the St. Lawrence Seaway was subsequently approved by legisla-

tion); and adherence to the Permanent Court of International Justice, January 29, 1935.

5

See Chapter III for references and additional discussion.

ingful, the doctrine of obligatory ratification was for all practical

purposes abandoned.

Although Senators sometimes play a part in the initiation or de-

velopment of a treaty, the Senate role now is primarily to pass

judgment on whether completed treaties should be ratified by the

United States. The Senate’s advice and consent is asked on the

question of Presidential ratification. When the Senate considers a

treaty it may approve it as written, approve it with conditions, re-

ject and return it, or prevent its entry into force by withholding ap-

proval. In practice the Senate historically has given its advice and

consent unconditionally to the vast majority of treaties submitted

to it.

In numerous cases, the Senate has approved treaties subject to

conditions. The President has usually accepted the Senate condi-

tions and completed the ratification process. In some cases, treaties

have been approved with reservations that were unacceptable ei-

ther to the President or the other party, and the treaties never en-

tered into force.

3

Only on rare occasions has the Senate formally rejected a treaty.

The most famous example is the Versailles Treaty, which was de-

feated on March 19, 1920, although 49 Senators voted in favor and

35 against. This was a majority but not the required two-thirds

majority so the treaty failed. Since then, the Senate has defini-

tively rejected only three treaties.

4

In addition, the Senate some-

times formally rejects treaties but keeps them technically alive by

adopting or entering a motion to reconsider. This has happened, for

instance, with the Optional Protocol Concerning the Compulsory

Settlement of Disputes in 1960, the Montreal Aviation Protocols

Nos. 3 and 4 in 1983, and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty in

1999.

More often the Senate has simply not voted on treaties that did

not have enough support for approval, and the treaties remained

pending in the Foreign Relations Committee for long periods. Even-

tually, unapproved treaties have been replaced by other treaties,

amended by protocols and then approved, or withdrawn by or re-

turned to the President. Thus the Senate has used its veto spar-

ingly, but still demonstrated the necessity of its advice and consent

and its power to block a treaty from entering into force.

TREATIES UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW

5

Under international law an international agreement is generally

considered to be a treaty and binding on the parties if it meets four

criteria:

(1) The parties intend the agreement to be legally binding and

the agreement is subject to international law;

(2) The agreement deals with significant matters;

(3) The agreement clearly and specifically describes the legal ob-

ligations of the parties; and

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00016 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

4

6

The Case-Zablocki Act (Public Law 92–403, as amended), is also examined in Chapter X. See

Appendix 2 for text of the law.

7

See Chapter IV for references and additional discussion. See also Chapter X.

8

See Chapter IV for references and additional discussion. See also Chapter X.

(4) The form indicates an intention to conclude a treaty, although

the substance of the agreement rather than the form is the govern-

ing factor.

International law makes no distinction between treaties and ex-

ecutive agreements. Executive agreements, especially if significant

enough to be reported to Congress under the Case-Zablocki Act, are

to all intents and purposes binding treaties under international

law.

6

On the other hand, many international undertakings and foreign

policy statements, such as unilateral statements of intent, joint

communiques, and final acts of conferences, are not intended to be

legally binding and are not considered treaties.

TREATIES UNDER U

.

S

.

LAW

7

Under the Constitution, a treaty, like a Federal statute, is part

of the ‘‘supreme Law of the Land.’’ Self-executing treaties, those

that do not require implementing legislation, automatically become

effective as domestic law immediately upon entry into force. Other

treaties do not become effective as domestic law until implementing

legislation is enacted, and then technically it is the legislation, not

the treaty unless incorporated into the legislation, that is the law

of the land.

Sometimes it is not clear on the face of a treaty whether it is

self-executing or requires implementing legislation. Some treaties

expressly call for implementing legislation or deal with subjects

clearly requiring congressional action, such as the appropriation of

funds or enactment of domestic penal provisions. The question of

whether or not a treaty requires implementing legislation or is self-

executing is a matter of interpretation largely by the executive

branch or, less frequently, by the courts. On occasion, the Senate

includes an understanding in the resolution of ratification that cer-

tain provisions are not self-executing or that the President is to ex-

change or deposit the instrument of ratification only after imple-

mentation legislation has been enacted.

When a treaty is deemed self-executing, it overrides any conflict-

ing provision of the law of an individual signatory state. If a treaty

is in irreconcilable conflict with a Federal law, the one executed

later in time prevails, although courts generally try to harmonize

domestic and international obligations whenever possible.

EXECUTIVE AGREEMENTS UNDER U

.

S

.

LAW

8

The status in domestic law of executive agreements, that is,

international agreements made by the executive branch but not

submitted to the Senate for its advice and consent, is less clear.

Three types of executive agreements and their domestic legal sta-

tus are discussed below.

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00017 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

5

(1) Congressional-executive agreements

Most executive agreements are either explicitly or implicitly au-

thorized in advance by Congress or submitted to Congress for ap-

proval. Some areas in which Congress has authorized the conclu-

sion of international agreements are postal conventions, foreign

trade, foreign military assistance, foreign economic assistance,

atomic energy cooperation, and international fishery rights. Some-

times Congress has authorized conclusion of agreements but re-

quired the executive branch to submit the agreements to Congress

for approval by legislation or for a specified waiting period before

taking effect. Congress has also sometimes approved by joint reso-

lution international agreements involving matters that are fre-

quently handled by treaty, including such subjects as participation

in international organizations, arms control measures, and acquisi-

tion of territory. The constitutionality of this type of agreement

seems well established and Congress has authorized or approved

them frequently,

(2) Agreements pursuant to treaties

Some executive agreements are expressly authorized by treaty or

an authorization for them may be reasonably inferred from the pro-

visions of a prior treaty. Examples include arrangements and un-

derstandings under the North Atlantic Treaty and other security

treaties. The President’s authority to conclude agreements pursu-

ant to treaties seems well established, although controversy occa-

sionally arises over whether particular agreements are within the

purview of an existing treaty.

(3) Presidential or sole executive agreements

Some executive agreements are concluded solely on the basis of

the President’s independent constitutional authority and do not

have an underlying explicit or implied authorization by treaty or

statute. Authorities from the Constitution that Presidents claim as

a basis for such agreements include:

—The President’s general executive authority in Article II, Sec-

tion 1, of the Constitution;

—His power as Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy in

Article II, Section 2, Clause 1;

—The treaty clause itself for agreements, which might be part of

the process of negotiating a treaty in Article II, Section 2,

Clause 2;

—His authority to receive Ambassadors and other public Min-

isters in Article II, Section 3; and

—His duty to ‘‘take care that the laws be faithfully executed’’ in

Article II, Section 3.

Courts have indicated that executive agreements based solely on

the President’s independent constitutional authority can supersede

conflicting provisions of state law, but opinions differ regarding the

extent to which they can supersede a prior act of Congress. What

judicial authority exists seems to indicate that they cannot.

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00018 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

6

9

See Chapter V for references and additional discussion.

STEPS IN THE U

.

S

.

PROCESS OF MAKING TREATIES AND EXECUTIVE

AGREEMENTS

Phases in the life of a treaty include negotiation and conclusion,

consideration by the Senate, Presidential ratification, implementa-

tion, modification, and termination. Following is a discussion of the

major steps and the roles of the President and the Senate in each

phase.

Executive agreements are negotiated and concluded in the same

way as treaties, but they do not go through the procedure for ad-

vice and consent of the Senate. Some executive agreements are

submitted to the Congress for approval and most are to be trans-

mitted to Congress after their conclusion. (See charts 1 and 2.)

Negotiation and conclusion

9

The first phase of treatymaking, negotiation and conclusion, is

widely considered an exclusive prerogative of the President except

for making appointments which require the advice and consent of

the Senate. The President chooses and instructs the negotiators

and decides whether to sign an agreement after its terms have

been negotiated. Nevertheless, the Senate or Congress sometimes

proposes negotiations and influences them through advice and con-

sultation. In addition, the executive branch is supposed to advise

appropriate congressional leaders and committees of the intention

to negotiate significant new agreements and consult them as to the

form of the agreement.

Steps in the negotiating phase follow.

(1) Initiation.—The executive branch formally initiates the nego-

tiations. The original concept or proposal for a treaty on a particu-

lar subject, however, may come from Congress.

(2) Appointment of negotiators.—The President selects the nego-

tiators of international agreements, but appointments may be sub-

ject to the advice and consent of the Senate. Negotiations are often

conducted by ambassadors or foreign service officers in a relevant

post who have already been confirmed by the Senate.

(3) Issuance of full powers and instructions.—The President

issues full power documents to the negotiators, authorizing them

officially to represent the United States. Similarly, he issues in-

structions as to the objectives to be sought and positions to be

taken. On occasion the Senate participates in setting the objectives

during the confirmation process, or Congress contributes to defin-

ing the objectives through hearings or resolutions.

(4) Negotiation.—Negotiation is the process by which representa-

tives of the President and other governments concerned agree on

the substance, terms, wording, and form of an international agree-

ment. Members of Congress sometimes provide advice through con-

sultations arranged either by Congress or the executive branch,

and through their statements and writings. Members of Congress

or their staff have served as members or advisers of delegations

and as observers at international negotiations.

(5) Conclusion.—The conclusion or signing marks the end of the

negotiating process and indicates that the negotiators have reached

agreement. In the case of a treaty the term ‘‘conclusion’’ is a mis-

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00019 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

7

10

See Chapter VI for references and additional discussion. Chapter VI also contains the text

of Senate Rule XXX.

nomer in that the agreement does not enter into force until the ex-

change or deposit of ratifications. In the case of executive agree-

ments, however, the signing and entry into force are frequently si-

multaneous.

Consideration by the Senate

10

A second phase begins when the President transmits a concluded

treaty to the Senate and the responsibility moves to the Senate.

Following are the main steps during the Senate phase.

(1) Presidential submission.—The Secretary of State formally

submits treaties to the President for transmittal to the Senate. A

considerable time may elapse between signature and submission to

the Senate, and on rare occasions a treaty signed on behalf of the

United States may never be submitted to the Senate at all and

thus never enter into force for the United States. When transmit-

ted to the Senate, treaties are accompanied by a Presidential mes-

sage consisting of the text of the treaty, a letter of transmittal re-

questing the advice and consent of the Senate, and the earlier let-

ter of submittal of the Secretary of State which usually contains a

detailed description and analysis of the treaty.

(2) Senate receipt and referral.—The Parliamentarian transmits

the treaty to the Executive Clerk, who assigns it a document num-

ber. The Majority Leader then, as in executive session, asks the

unanimous consent of the Senate that the injunction of secrecy be

removed, that the treaty be considered as having been read the

first time, and that it be referred to the Foreign Relations Commit-

tee and ordered to be printed. The Presiding Officer then refers the

treaty, regardless of its subject matter, to the Foreign Relations

Committee in accordance with Rule XXV of the Senate Rules. (Rule

XXV makes an exception only for reciprocal trade agreements.) At

this point the treaty text is printed and made available to the pub-

lic.

(3) Senate Foreign Relations Committee action.—The treaty is

placed on the committee calendar and remains there until the com-

mittee reports it to the full Senate. While it is committee practice

to allow a treaty to remain pending long enough to receive study

and comments from the public, the committee usually considers a

treaty within a year or two, holding a hearing and preparing a

written report.

The committee recommends Senate advice and consent by report-

ing a treaty with a proposed resolution of ratification. While most

treaties have historically been reported without conditions, the

committee may recommend that the Senate approve a treaty sub-

ject to conditions incorporated in the resolution of ratification.

(4) Conditional approval.—The conditions traditionally have been

grouped into categories described in the following way.

—Amendments to a treaty change the text of the treaty and re-

quire the consent of the other party or parties. (Note that in

Senate debate the term may refer to an amendment of the res-

olution of ratification, not the treaty itself, and therefore be

comprised of some other type of condition.)

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00020 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

8

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00021 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

9

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00022 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

10

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00023 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

11

—Reservations change U.S. obligations without necessarily

changing the text, and they require the acceptance of the other

party.

—Understandings are interpretive statements that clarify or

elaborate provisions but do not alter them.

—Declarations are statements expressing the Senate’s position or

opinion on matters relating to issues raised by the treaty rath-

er than to specific provisions.

—Provisos relate to issues of U.S. law or procedure and are not

intended to be included in the instruments of ratification to be

deposited or exchanged with other countries.

Whatever name a condition is given by the Senate, if a condition

alters an international obligation under the treaty, the President is

expected to transmit it to the other party. In recent years, the Sen-

ate on occasion has explicitly designated that some conditions were

to be transmitted to the other party or parties and, in some cases,

formally agreed to by them. It has also designated that some condi-

tions need not be formally communicated to the other party, that

some conditions were binding on the President, and that some con-

ditions expressed the intent of the Senate.

(5) Action by the full Senate.—After a treaty is reported by the

Foreign Relations Committee, it is placed on the Senate’s Executive

Calendar and the Majority Leader arranges for the Senate to con-

sider it. In 1986 the Senate amended Rule XXX of the Senate

Rules, which governs its consideration of treaties, to simplify the

procedure in this step. Still, under the full procedures of the re-

vised Rule XXX, in the first stage of consideration the treaty would

be read a second time and any proposed amendments to the treaty

itself would be considered and voted upon by a simple majority.

Usually the Majority Leader obtains unanimous consent to abbre-

viate the procedures, and the Senate proceeds directly to the con-

sideration of the resolution of ratification as recommended by the

Foreign Relations Committee.

The Senate then considers amendments to the resolution of rati-

fication, which would incorporate any amendments to the treaty

itself that the Senate had agreed to in the first stage, as well as

conditions recommended by the Foreign Relations Committee. Sen-

ators may then offer reservations, understandings, and other condi-

tions to be placed in the resolution of ratification. Votes on these

conditions, as well as other motions, are determined by a simple

majority. Finally, the Senate votes on the resolution of ratification,

as it has been amended. The final vote on the resolution of ratifica-

tion requires, for approval, a two-thirds majority of the Senators

present. Although the number of Senators who must be present is

not specified, the Senate’s practice with respect to major treaties is

to conduct the final treaty vote at a time when most Senators are

available. After approval of a controversial treaty, a Senator may

offer a motion to reconsider which is usually laid on the table (de-

feated). In the case of a treaty that has failed to receive a two-

thirds majority, if the motion to reconsider is not taken up, the

treaty is returned to the Foreign Relations Committee. Prior to the

final vote on the resolution of ratification, a Senator may offer a

substitute amendment, proposing that the Senate withhold its ad-

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00024 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

12

11

See Chapter VII for references and additional discussion.

12

See Chapter VIII for references and additional discussion.

13

In addition to Chapter VIII, see Chapter X.

vice and consent, or offer a motion to recommit the resolution to

the Foreign Relations Committee.

(6) Return to committee.—Treaties reported by the committee but

neither approved nor formally returned to the President by the

Senate are automatically returned to the committee calendar at the

end of a Congress; the committee must report them out again in

order for the Senate to consider them.

(7) Return to President or withdrawal.—The President may re-

quest the return of a treaty, or the Foreign Relations Committee

may report and the Senate adopt a simple resolution directing the

Secretary of the Senate to return a treaty to the President. Other-

wise, treaties that do not receive the advice and consent of the Sen-

ate remain pending on the committee calendar indefinitely.

Presidential action after Senate action

11

After the Senate gives its advice and consent to a treaty, the

Senate sends it to the President. He resumes control and decides

whether to take further action to complete the treaty.

(1) Ratification.—The President ratifies a treaty by signing an in-

strument of ratification, thus declaring the consent of the United

States to be bound. If the Senate has consented with reservations

or conditions that the President deems unacceptable, he may at a

later date resubmit the original treaty to the Senate for further

consideration, or he may renegotiate it with the other parties prior

to resubmission. Or the President may decide not to ratify the trea-

ty because of the conditions or for any other reason.

(2) Exchange or deposit of instruments of ratification and entry

into force.—If he ratifies the treaty, the President then directs the

Secretary of State to take any action necessary for the treaty to

enter into force. A bilateral treaty usually enters into force when

the parties exchange instruments of ratification. A multilateral

treaty enters into force when the number of parties specified in the

treaty deposit the instruments of ratification at a specified location.

Once a treaty enters into force, it is binding in international law

on the parties who have ratified it.

(3) Proclamation.—When the instruments of ratification have

been exchanged or the necessary number deposited, the President

issues a proclamation that the treaty has entered into force. Procla-

mation serves as legal notice for domestic purposes and publicizes

the text.

Implementation

12

The executive branch has the primary responsibility for carrying

out treaties and ascertaining that other parties fulfill their obliga-

tions after treaties and other international agreements enter into

force, but the Senate or the entire Congress share in the following

phases.

(1) Implementing legislation.

13

—When implementing legislation

or appropriations are needed to carry out the terms of a treaty, it

VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:52 Mar 05, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00025 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\TREATIES\66922 CRS1 PsN: CRS1

13

14

In addition to Chapter VIII, see Chapter VI, and discussion of INF Treaty in Chapter XI.

15

See Chapter IX for references and additional discussion.

must go through the full legislative process including passage by

both Houses and presentment to the President.

(2) Interpretation.

14

—The executive branch interprets the re-

quirements of an agreement as it carries out its provisions. U.S.

courts may also interpret a treaty’s effect as domestic law in appro-

priate cases. The Senate has made clear that the United States is