International Law and Agreements:

Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Updated July 13, 2023

Congressional Research Service

https://crsreports.congress.gov

RL32528

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service

International Law and Agreements:

Their Effect upon U.S. Law

International law is derived primarily from two sources: international agreements and

customary international practice. Under U.S. law, the United States enters into

international agreements by either executing a treaty or an executive agreement. The

Constitution gives primary responsibility for entering into international agreements to

the executive branch, but Congress plays an essential role in several ways. First, for a

treaty (but not an executive agreement) to become binding upon the United States, the Senate must provide

its advice and consent to ratification by a two-thirds majority. Second, a category of agreements known as

congressional-executive agreements are made by the executive branch with the approval of Congress

through the normal legislative process. Third, many treaties and executive agreements have provisions that

are not self-executing, meaning that Congress must enact implementing legislation to make the provisions

judicially enforceable in the United States.

An international agreement’s status in relation to U.S. law depends on many factors. Self-executing treaties

have a status equal to federal statutes, superior to U.S. state laws and inferior to the Constitution.

Depending on their nature, executive agreements may or may not have a status equal to a federal statute.

Non-self-executing provisions in treaties and executive agreements occupy a complex place in the U.S.

legal system. While non-self-executing provisions bind the United States as a matter of international law,

they do not create rights or obligations enforceable as domestic law in U.S. courts.

Along with legally binding agreements, the executive branch regularly enters into non-binding instruments

with foreign entities. The formality, specificity, and duration of these instruments may vary considerably,

but non-binding instruments do not modify existing legal authorities, which remain controlling under both

U.S. domestic and international law. While they do not create new legal obligations, non-binding

instruments may still carry significant moral and political incentives for compliance.

The second major source of international law is customary international practice. While its effects upon

domestic law are more difficult to discern, more than a century ago the Supreme Court observed that

customary international law is “part of” U.S. law, notwithstanding domestic statutes that conflict with

customary international rules. Scholars have debated whether the Supreme Court’s customary international

law jurisprudence still applies in the modern era. In addition, some domestic U.S. statutes directly

incorporate customary international law and therefore invite courts to interpret and apply this body of law

in the domestic legal system. The Alien Tort Statute serves as one example, as it establishes federal court

jurisdiction over tort claims brought by aliens for violating “the law of nations.” Because the legislative

branch possesses important powers to shape and define the United States’ international obligations,

Congress is likely to continue to play a critical role in shaping international law’s status in the U.S. legal

system.

RL32528

July 13, 2023

Stephen P. Mulligan

Legislative Attorney

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service

Contents

Forms of International Commitments ............................................................................................. 5

Treaties ...................................................................................................................................... 6

Executive Agreements ............................................................................................................... 8

Types of Executive Agreements .......................................................................................... 8

Mixed Sources of Authority for Executive Agreements .................................................... 11

Choosing Between a Treaty and an Executive Agreement ............................................... 12

Non-Binding Instruments ........................................................................................................ 15

Transparency Requirements .................................................................................................... 16

Qualifying Non-Binding Instruments ............................................................................... 17

Congressional Reporting and Publication Requirements .................................................. 18

Other Oversight and Transparency Provisions .................................................................. 19

Effects of International Agreements on U.S. Law ......................................................................... 20

Self-Executing vs. Non-Self-Executing Agreements .............................................................. 20

Congressional Implementation of International Agreements .................................................. 22

Conflict with Existing Laws .................................................................................................... 24

Interpreting International Agreements ........................................................................................... 26

Withdrawal from International Agreements .................................................................................. 27

Withdrawal from Executive Agreements and Political Commitments .................................... 28

Withdrawal from Treaties ........................................................................................................ 30

Customary International Law ........................................................................................................ 33

Relationship Between Customary International Law and Domestic Law............................... 34

Statutory Incorporation of Customary International Law and the Alien Tort Statute ............. 36

Conclusion ..................................................................................................................................... 37

Figures

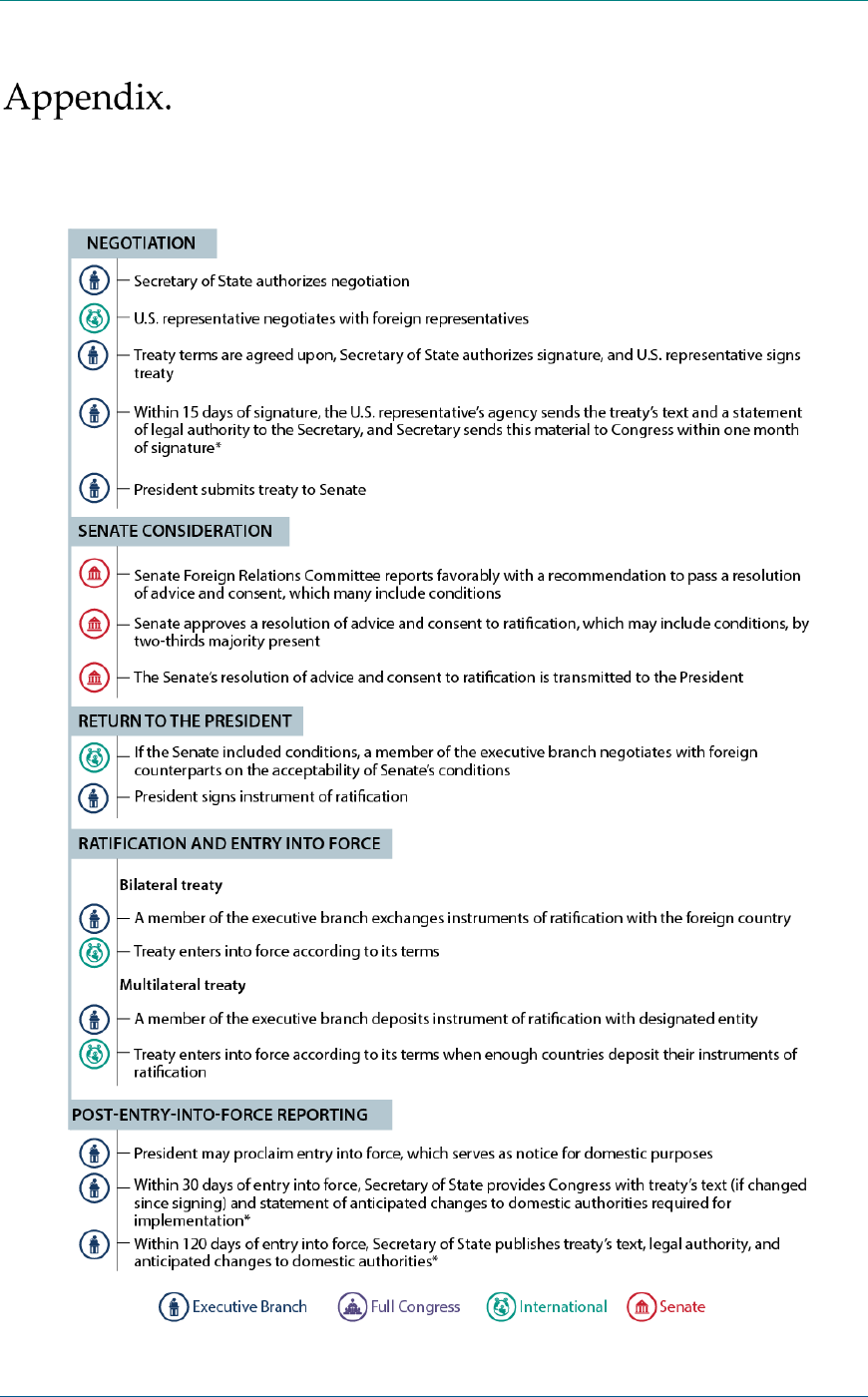

Figure A-1: Steps in Making a Treaty ........................................................................................... 39

Figure A-2: Steps in Making an Executive Agreement ................................................................. 40

Appendixes

Steps in Making a Treaty or Executive Agreement ..................................................... 39

Contacts

Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 41

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 4

nternational law consists of “rules and principles of general application dealing with the

conduct of states and of international organizations and with their relations inter se, as well as

with some of their relations with persons, whether natural or juridical.”

1

While U.S. courts

and officials have long recognized that international law can create legally binding rights and

obligations for the United States, international law’s exact role in the U.S. legal system implicates

complex legal dynamics.

2

The United States takes on new international obligations most often through treaties and other

international agreements.

3

The Constitution vests the power to make treaties in the President, “by

and with the advice and consent of the Senate,”

4

but the United States does not make most

international commitments

5

through this constitutionally defined process. The President regularly

concludes executive agreements and non-binding instruments, which are not mentioned in the

Constitution and are not submitted to the Senate for advice and consent.

6

These international

commitments’ effect on U.S. law depends on what form the commitment takes and whether the

commitment requires implementing legislation from Congress to be judicially enforceable.

7

The United States is also bound by customary international law, which is derived from countries’

general and consistent practice arising out of a sense of legal obligation.

8

In a 1900 opinion, the

Supreme Court described customary international law as “part of our law,”

9

but scholars debate

whether 20th-century legal developments fundamentally altered customary international law’s

role in the U.S. legal system.

10

This report introduces the primary forms of international law and examines their effect on U.S.

law. It also highlights issues that may be particularly relevant to Congress, including the Senate’s

advice and consent function, Congress’s role in interpreting and implementing international

agreements, and the executive branch’s obligations to consult with and report to Congress about

international commitments.

1

RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW OF THE UNITED STATES § 101 (AM. L. INST. 1987) [hereinafter

THIRD RESTATEMENT]. Although originally limited to nation-to-nation relations, international law grew in the 20th

century with the fields of human rights law and international criminal law to regulate individuals’ conduct in some

circumstances. See, e.g., G.A. Res. 217 (III) (Dec. 10, 1948); Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of

Prisoners of War, Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3316, 75 U.N.T.S. 135; Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of

Civilian Persons in Time of War, Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3516, 75 U.N.T.S. 287; G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI) (Dec. 16,

1966; U.N. GAOR, 21st Sess., 1496th plen. mtg., U.N. Doc. A/RES/2200A (XXI) (Dec. 16, 1966).

2

See, e.g., Ware v. Hylton, 3 U.S. (3 Dall.) 199, 281 (1796) (“When the United States declared their independence,

they were bound to receive the law of nations, in its modern state of purity and refinement.”); Chisholm v. Georgia,

2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 419, 474 (1793) (“[T]he United States had, by taking a place among the nations of the earth, become

amenable to the law of nations.”); Letter from Thomas Jefferson, Sec’y of State, to Edmond Charles Genet, French

Minister (June 5, 1793), in JEFFERSON PAPERS, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-26-02-0189

(describing the law of nations as an “integral part” of domestic law).

3

See infra “Forms of International Commitments.”

4

U.S. CONST. art. II, § 2, cl. 2.

5

As used in this report, the term commitment is a generic term intended to encompass all forms of legally binding

agreements and non-binding instruments.

6

See infra “Forms of International Commitments.”

7

See infra “Effects of International Agreements on U.S. Law.”

8

See, e.g., THIRD RESTATEMENT, supra note 1, § 102(2).

9

The Paquete Habana, 175 U.S. 677, 700 (1900).

10

See infra “Relationship Between Customary International Law and Domestic Law.”

I

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 5

Forms of International Commitments

For purposes of U.S. law and practice, international commitments between the United States and

foreign nations may take the form of treaties, executive agreements, or non-binding instruments.

11

When using these terms, there are important distinctions between international legal parlance and

domestic American usage. International agreement is a blanket term used to refer to any

agreement between the United States and a foreign state or body that is binding under

international law.

12

In international law, treaty and international agreement are synonymous terms

that refer to any binding agreement.

13

In the context of domestic law, treaty generally refers to a

narrower subcategory of binding international agreements that receives the Senate’s advice and

consent.

14

This report follows the domestic usage unless otherwise noted.

11

For further detail of various types of international commitments and their relationship with U.S. law, see CONG.

RSCH. SERV., 106TH CONG., REP. ON TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS: THE ROLE OF THE UNITED

STATES SENATE 43–97 (Comm. Print 2001) [hereinafter TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS], available

at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-106SPRT66922/pdf/CPRT-106SPRT66922.pdf; Curtis A. Bradley &

Jack L. Goldsmith, Presidential Control Over International Law, 131 HARV. L. REV. 1201, 1207–09 (2018).

12

RESTATEMENT (FOURTH) OF THE FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW OF THE UNITED STATES § 301 cmt. a (AM. L. INST. 2018)

[hereinafter FOURTH RESTATEMENT]. See also James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year

2023, Pub. L. No. 117-263, 136 Stat. 2395, 2600 (2022) (to be codified in 1 U.S.C. § 112b(k)(4)(A)) [hereinafter 2023

NDAA].

13

See Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties art. 2, Apr. 24, 1970, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331 [hereinafter Vienna

Convention]. Although the United States has not ratified the Vienna Convention, courts and the executive branch

generally regard it as reflecting customary international law on many matters. See, e.g., De Los Santos Mora v. New

York, 524 F.3d 183, 196 n.19 (2d Cir. 2008) (“Although the United States has not ratified the Vienna Convention on

the Law of Treaties, our Court relies upon it ‘as an authoritative guide to the customary international law of treaties,’

insofar as it reflects actual state practices.”) (quoting Avero Belg. Ins. v. Am. Airlines, Inc., 423 F.3d 73, 80 n.8 (2d

Cir. 2005)); Fujitsu Ltd. v. Fed. Express Corp., 247 F.3d 423, 433 (2d Cir. 2001) (“[W]e rely upon the Vienna

Convention here as an ‘authoritative guide to the customary international law of treaties.’ ”) (quoting Chubb & Son,

Inc. v. Asiana Airlines, 214 F.3d 301, 309 (2d Cir. 2000)). But see THIRD RESTATEMENT, supra note 1, § 208 reporters’

n.4 (“[T]he [Vienna] Convention has not been ratified by the United States and, while purporting to be a codification of

preexisting customary law, it is not in all respects in accord with the understanding and the practice of the United States

and of some other states.”); The Administration’s Proposal for a U.N. Resolution on the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-

Ban Treaty: Hearing Before the Sen. Comm. on Foreign Relations, 114th Cong. (2016) (statement of Stephen G.

Rademaker, Principal, The Podesta Grp.), https://www.foreign.senate.gov/download/090716_rademaker_testimony

[hereinafter Rademaker Statement] (“[T]he more correct statement with respect to the Vienna Convention would be

that in the opinion of the Executive branch it generally reflects customary international law, but, in the opinion of the

Senate, in important respects it does not.”).

14

See, e.g., 2023 NDAA, 136 Stat. 2600 (codified in 1 U.S.C. § 112b(k)(4)(A)); FOURTH RESTATEMENT, supra note 12,

§ 301 cmt. a. Under U.S. law, the term treaty is not always interpreted to refer only to those agreements described in

Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution. See Weinberger v. Rossi, 456 U.S. 25, 31–32 (1982) (interpreting statute

barring discrimination except where permitted by “treaty” to refer to both treaties and executive agreements);

B. Altman & Co. v. United States, 224 U.S. 583, 601 (1912) (construing the term treaty, as used in statute conferring

appellate jurisdiction, to also refer to executive agreements).

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 6

Forms of International Commitments

International agreement: A blanket term used to refer to any agreement between the United States and a

foreign state or body that is binding under international law.

15

Treaty: An international agreement that receives the advice and consent of the Senate and is ratified by the

President through the process defined in the Treaty Clause.

16

Executive agreement: An international agreement that is binding but which the President enters into without

receiving the advice and consent of the Senate.

17

Non-binding instrument: An instrument between the United States and a foreign entity that is not binding

under international law but may carry non-legal incentives for compliance.

18

Treaties

Under U.S. law, a treaty is an agreement negotiated and signed by a member of the executive

branch that enters into force if approved by a two-thirds majority of the Senate and ratified by the

President.

19

Most modern treaties require parties to exchange or deposit instruments of ratification

to enter into force.

20

A chart depicting the steps necessary for the United States to enter into a

treaty is in the Appendix.

The Treaty Clause—Article II, Section 2, clause 2, of the Constitution—vests the power to make

treaties in the President, acting with the “advice and consent” of the Senate.

21

Many scholars have

concluded that the Framers intended “advice” and “consent” to be separate aspects of the treaty-

making process.

22

According to this interpretation, the “advice” element required the President to

consult the Senate during treaty negotiations before seeking the Senate’s final “consent.”

23

Early

in his presidency, President George Washington appears to have followed the process that the

Senate had such a consultative role,

24

but he and other early Presidents soon declined to seek the

15

FOURTH RESTATEMENT, supra note12, § 301 cmt. a. See also 2023 NDAA, 136 Stat. 2600 (codified in 1 U.S.C.

§ 112b(k)(4))

16

See 2023 NDAA, supra note 14; FOURTH RESTATEMENT, supra note 12, § 301 cmt. a.; Weinberger, 456 U.S. at 31–

32 (1982); B. Altman, 224 U.S. at 601.

17

See infra “Executive Agreements.”

18

See infra Non-Binding Instruments.”

19

See FOURTH RESTATEMENT, supra note 12, § 301 cmt. a.

20

See id. § 304 cmt. a (“Some agreements provide that they are binding upon signature alone, although signature ad

referendum (that is, subject to confirmation through some subsequent act) is frequently employed.”); Curtis A. Bradley,

Unratified Treaties, Domestic Politics and the U.S. Constitution, 48 HARV. INT’L L.J. 307, 313 (2007) (“Under modern

practice ... consent is manifested through a subsequent act of ratification—the deposit of an instrument of ratification or

accession with a treaty depositary in the case of multilateral treaties, and the exchange of instruments of ratification in

the case of bilateral treaties.”).

21

For additional background on the Treaty Clause, see Cong. Research Serv., Treaty Clause: Overview of the

President’s Treaty-Making Power, CONSTITUTION ANNOTATED, https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/artII-S2-

C2-1-1/ALDE_00012952/ (last visited Jan 12, 2023).

22

See, e.g., LOUIS HENKIN, FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND THE U.S. CONSTITUTION 177 (2d ed. 1996); Arthur Bestor, “Advice”

from the Very Beginning, “Consent” When the End Is Achieved, 83 AM. J. INT’L L. 718, 726 (1989).

23

See supra note 22.

24

On the occasion that scholars have described as the first and last time the President personally visited the Senate

chamber to receive the Senate’s advice on a treaty, President Washington went to the Senate in August 1789 to consult

about proposed treaties with the Southern Indians. See 1 ANNALS OF CONG. 65–71 (1789). Observers reported that he

was so frustrated with the experience that he vowed never to appear in person to discuss a treaty again. See, e.g.,

WILLIAM MACLAY, SKETCHES OF DEBATE IN THE FIRST SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES 122–24 (George W. Harris ed.,

1880) (record of the President’s visit by Senator William Maclay of Pennsylvania); RALSTON HAYDEN, THE SENATE

AND TREATIES, 1789–1817, at 21–26 (1920) (providing a historical account of Washington’s visit to the Senate).

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 7

Senate’s input during the negotiation process.

25

In modern treaty-making practice, the executive

branch generally assumes responsibility for negotiations, and the Supreme Court has stated that

the President’s constitutional power to conduct treaty negotiations is exclusive.

26

Although Presidents generally do not consult the Senate during treaty negotiations, the Senate

maintains an aspect of its “advice” function by providing conditional consent.

27

In considering a

treaty, the Senate may condition its consent on proposed conditions known as reservations,

28

understandings,

29

or declarations

30

(RUDs).

31

The Senate has sometimes imposed other

requirements under other labels such as condition

32

or proviso,

33

which often set forth procedural

requirements for ratifying or implementing a treaty.

34

Under established U.S. practice, the

President cannot ratify a treaty unless the President accepts the Senate’s RUDs and other

conditions.

35

If accepted by the President, RUDs and other conditions may modify or define U.S.

25

See MEMOIRS OF JOHN QUINCY ADAMS 427 (Charles Francis Adams ed., 1875) (“[E]ver since [President

Washington’s first visit to the Senate to seek its advice], treaties have been negotiated by the Executive before

submitting them to the consideration of the Senate.”).

26

See Zivotofsky v. Kerry, 576 U.S. 1, 13 (2015) (“The President has the sole power to negotiate treaties.... ”); United

States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., 299 U.S. 304, 319 (1936).

27

Accord Curtis A. Bradley & Jack L. Goldsmith, Treaties, Human Rights, and Conditional Consent, 149 U. PA. L.

REV. 399, 405 (2000) (“The exercise of the conditional consent power has been in part a response by the Senate to its

loss of any substantial ‘advice’ role in the treaty process.”); SAMUEL B. CRANDALL, TREATIES, THEIR MAKING AND

ENFORCEMENT 81 (2d ed. 1916) (“Not usually consulted as to the conduct of negotiations, the Senate has freely

exercised its co-ordinate power in treaty making by means of amendments.”).

28

As a general matter, “[r]eservations change U.S. obligations without necessarily changing the text, and they require

the acceptance of the other party.” See TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra note 11, at 11.

Accord FOURTH RESTATEMENT, supra note 12, § 305 reporters’ n.2 (“Although the Senate has not been entirely

consistent in its use of the labels, in general the label ... ‘reservation’ [has been used] when seeking to limit the effect of

the existing text for the United States.”).

29

Understandings are “interpretive statements that clarify or elaborate provisions but do not alter them.” TREATIES AND

OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra note 11, at 11. Accord FOURTH RESTATEMENT, supra note 12, § 305

reporters’ n.5.B (“The Senate has regularly used ‘understandings’ to set forth the U.S. interpretation of particular treaty

provisions.”).

30

Declarations are “statements expressing the Senate’s position or opinion on matters relating to issues raised by the

treaty rather than to specific provisions.” TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra note 11, at 11. See

also FOURTH RESTATEMENT, supra note 12, § 305 reporters’ n.5.E (“The Senate sometimes uses ‘declarations’ to

express views on matters of policy.”).

31

For additional background on RUDs, see CRS In Focus IF12208, Reservations, Understandings, Declarations, and

Other Conditions to Treaties, by Stephen P. Mulligan.

32

See, e.g., Resolution of Advice and Consent to Ratification of Protocols to the North Atlantic Treaty of 1949 on the

Accession of the Republic of Finland and the Kingdom of Sweden § 3, S. TREATY DOC. 117-3, available at

https://www.congress.gov/treaty-document/117th-congress/3/resolution-text (providing advice and consent subject to

the condition that the President make certain certifications to the Senate).

33

See, e.g., Resolution of Advice and Consent to Ratification of the Food Aid Convention 1999 § 3(b), S. TREATY

DOC.106-4, available at https://www.congress.gov/treaty-document/106th-congress/14/resolution-text (providing

advice and consent subject to the provision that “Nothing in the Convention requires or authorizes legislation or other

action by the United States of America that is prohibited by the Constitution of the United States as interpreted by the

United States”).

34

Procedural matters include requirements that the President make certifications to the Senate, produce reports, or

consult certain congressional committees on issues the treaty raises. See TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL

AGREEMENTS, supra note 11, at 11; FOURTH RESTATEMENT, supra note 14, § 305 reporters’ n.2.

35

FOURTH RESTATEMENT, supra note 12, § 305 reporters’ n.4. See also United States v. Stuart, 489 U.S. 353, 374–75

(1989) (Scalia, J., concurring) (“[The Senate] may, in the form of a resolution, give its consent on the basis of

conditions. If these are agreed to by the President and accepted by the other contracting parties, they become part of the

treaty and of the law of the United States.... ”).

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 8

rights and obligations under the treaty.

36

The Senate may also propose to amend the text of the

treaty itself, and other nations that are parties to the treaty must consent to the changes for them to

take effect.

37

Executive Agreements

The great majority of international agreements that the United States enters into are not treaties

but executive agreements—agreements entered into by the executive branch that are not

submitted to the Senate for its advice and consent.

38

The Constitution does not specifically

discuss executive agreements, but they have still been considered valid international agreements

under Supreme Court jurisprudence and as a matter of historical practice.

39

The United States has

made executive agreements since the earliest days of the Republic,

40

and their use increased

significantly in the post–World War II era.

41

Commentators estimate that more than 90% of the

United States’ international agreements have been in the form of an executive agreement.

42

Types of Executive Agreements

There are three categories of executive agreements—congressional-executive agreements,

executive agreements made pursuant to a treaty, and sole executive agreements. Executive

agreements are traditionally categorized based upon the source of the President’s authority to

conclude them. In the case of congressional-executive agreements, Congress provides the

President with domestic authority through legislation enacted through the bicameral process.

43

36

For discussion of historical examples of conditions attached by the Senate to treaties, see FOURTH RESTATEMENT,

supra note 12, § 305 reporters’ n.5.

37

For example, in giving its advice and consent to the first treaty that was to be ratified by the United States after the

adoption of the Constitution—dubbed the Jay Treaty because it was negotiated by the first Supreme Court Chief Justice

of the United States, John Jay, who was appointed a special envoy to Great Britain despite his role in the judicial

branch—the Senate insisted on suspending an article allowing Great Britain to restrict U.S. trade in the British West

Indies. S. EXEC. JOURNAL, 4th Cong., Spec. Sess. 186 (1795). Great Britain ratified the Jay Treaty without objection to

the Senate’s changes. See HAYDEN, supra note 24, at 86–88.

38

See infra notes 40–42 (discussing historical usage of executive agreements and related judicial opinions).

39

See, e.g., Am. Ins. Ass’n v. Garamendi, 539 U.S. 396, 415 (2003) (“[O]ur cases have recognized that the President

has authority to make ‘executive agreements’ with other countries, requiring no ratification by the Senate or approval

by Congress, this power having been exercised since the early years of the Republic.”); Dames & Moore v. Regan, 453

U.S. 654, 680 (1981) (recognizing presidential power to settle claims of U.S. nationals and concluding “that Congress

has implicitly approved the practice of claim settlement by executive agreement”); United States v. Belmont, 301 U.S.

324, 330 (1937) (“[A]n international compact ... is not always a treaty which requires the participation of the Senate.”).

40

See, e.g., Garamendi, 539 U.S. at 415 (discussing “executive agreements to settle claims of American nationals

against foreign governments” dating back to “as early as 1799”); Act of Feb. 20, 1792, ch. 8, § 26, 1 Stat. 239 (act

passed by the Second Congress authorizing postal-related executive agreements).

41

See TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra note 11, at 38; Oona A. Hathaway, Treaties’ End:

The Past, Present, and Future of International Lawmaking in the United States, 117 YALE L.J. 1236, 1288 (2008);

Bradley & Goldsmith, supra note 11, at 1210.

42

Bradley & Goldsmith, supra note 11, at 1213. See also TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra

11, at 40.

43

Congress sometimes enacts legislation that pre-authorizes the President to conclude executive agreements on certain

subjects or within certain parameters. See, e.g., CLOUD Act, Pub. L. No. 115-141, div. V, § 105, 132 Stat. 1213, 1217

(2018) (codified at 18 U.S.C. § 2523) (authorizing data-sharing executive agreements with certain foreign nations);

Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, Pub. L. No. 87-195, 75 Stat. 424 (codified as amended at 22 U.S.C. §§ 2151–2431k)

(authorizing the President to furnish assistance to foreign nations “on such terms and conditions as he may determine,

to any friendly country”). Pre-authorized agreements are sometimes referred to as ex ante agreements. On other

occasions, Congress enacts legislation approving agreements that the President already negotiated and signed. See, e.g.,

(continued...)

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 9

The President also enters into executive agreements made pursuant to a treaty based on authority

granted to the President in prior Senate-approved, ratified treaties.

44

In other cases, the President

enters into sole executive agreements based on a claim of independent presidential power in the

Constitution.

45

A chart describing the steps in making an executive agreement is in the Appendix.

Categories of Executive Agreements

Congressional-executive agreement: an executive agreement that Congress authorizes through legislation

enacted through the bicameral process.

46

Executive agreement made pursuant to a treaty: an executive agreement based on the President’s

authority in a treaty previously approved by the Senate.

Sole executive agreement: an executive agreement based on the President’s constitutional powers.

Congressional-Executive Agreements

Congressional-executive agreements have long-standing historical precedent dating to the Second

Congress.

47

The Supreme Court has never directly addressed the constitutionality of

congressional-executive agreements, but it has recognized that the United States possesses the

“power to make such international agreements as do not constitute treaties in the constitutional

sense.”

48

The Court has also stated that, while a congressional-executive agreement may lack the

“dignity” of a Senate-approved treaty, it is still a valid international instrument.

49

Whereas only

the Senate gives consent to treaties, both houses of Congress are involved in authorizing

congressional-executive agreements.

50

Historically, congressional-executive agreements have

covered many topics ranging from postal conventions to bilateral trade to military assistance.

51

United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement Implementation Act, Pub. L. No. 116-113, § 101 (2020) (providing

approving for the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement Implementation Act). Agreements authorized after

conclusion are sometimes referred to as ex post agreements.

44

See THIRD RESTATEMENT, supra note 1, § 303(3); TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra note 11,

at 86.

45

See TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra note 11, at 88. See also supra note 39 (citing

Supreme Court case law recognizing the validity of sole executive agreements).

46

For background on methods of legislative approval for congressional-executive agreements, see supra note 43.

47

The Second Congress enacted legislation in 1792 authorizing the postmaster general to “make arrangements with the

postmasters in any foreign country for the reciprocal receipt and delivery of letters and packets, through the post

offices.” Act of Feb. 20, 1792, ch. 8, § 26, 1 Stat. 239.

48

United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., 299 U.S. 304, 318 (1936).

49

See B. Altman & Co. v. United States, 224 U.S. 583, 601 (1912) (“While it may be true that this commercial

agreement, made under authority of the tariff act of 1897, § 3, was not a treaty possessing the dignity of one requiring

ratification by the Senate of the United States, it was an international compact, negotiated between the representatives

of two sovereign nations, and made in the name and on behalf of the contracting countries, and dealing with important

commercial relations between the two countries, and was proclaimed by the President. If not technically a treaty

requiring ratification, nevertheless it was a compact authorized by the Congress of the United States, negotiated and

proclaimed under the authority of its President.”).

50

Congress authorizes congressional-executive agreements through legislation enacted through the bicameral process,

which involves both houses of Congress. For background on bicameralism, see Cong. Research Serv., Bicameralism,

CONSTITUTION ANNOTATED, https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/artI-S1-3-4/ALDE_00013293// (last visited

June. 21, 2023).

51

See TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra note 11, at 5.

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 10

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

52

and the 1947 General Agreement on

Tariffs and Trade

53

are notable examples of congressional-executive agreements.

Executive Agreements Pursuant to Treaties

The Supreme Court has given effect to at least one executive agreement made pursuant to a

treaty.

54

Executive agreements made pursuant to treaties can arise in many contexts. For example,

treaties that authorize the United States to operate military facilities in foreign countries often

require additional agreements related to activities and personnel at the base.

55

Other treaties create

international commissions that make recommendations on how to resolve matters such as

boundary delimitation and allocation of transnational water bodies.

56

These treaties may empower

the executive branch to conclude new agreements accepting the commissions’

recommendations.

57

Controversy occasionally arises as to whether a particular treaty actually

authorizes the executive to conclude an agreement in question.

58

Sole Executive Agreements

Sole executive agreements rely on neither treaty nor congressional authority to provide their legal

basis.

59

The Constitution confers at least some authority to the President to make sole executive

agreements based on the President’s powers defined in Article II.

60

The Supreme Court has

recognized the power of the President to conclude sole executive agreements in the context of

settling claims with foreign nations.

61

Examples of sole executive agreements include the 1933

Litvinov Assignment, under which the Soviet Union purported to assign to the United States

claims to American assets in Russia that had been nationalized by the Soviet Union, and the 1973

Vietnam Peace Agreement ending the United States’ participation in the war in Vietnam.

62

52

North American Free Trade Agreement, Can.-Mex.-U.S., Dec. 17, 1992, 32 I.L.M. 605 (entered into force Jan. 1,

1994).

53

See General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, Oct. 30, 1947, 61 Stat. A3.

54

See Wilson v. Girard, 354 U.S. 524, 526–30 (1957) (giving effect to administrative agreement authorized under the

bilateral U.S.-Japan Security Treaty).

55

For example, the United States acquired the naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, through an executive agreement

authorized by a 1903 treaty. See CRS Report R44137, Naval Station Guantanamo Bay: History and Legal Issues

Regarding Its Lease Agreements, by Jennifer K. Elsea, at 7.

56

The binational International Boundary and Water Commission, for example, was created by a series of U.S.-Mexico

treaties and is authorized to make decisions, called “minutes,” that the United States can approve on a case-by-case

basis. See CRS Report R45430, Sharing the Colorado River and the Rio Grande: Cooperation and Conflict with

Mexico, by Nicole T. Carter, Stephen P. Mulligan, and Charles V. Stern, at 3.

57

See, e.g., CRANDALL, supra note 27, at 179–119 (discussing acceptance of U.S.-British boundary delimitation).

58

See TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra note 11, at 86–87 n.117 (discussing examples in

which Members of the Senate contended that certain executive agreements did not fall within the purview of an

existing treaty and required Senate approval).

59

See Am. Ins. Ass’n v. Garamendi, 539 U.S. 396, 415 (2003) (“[O]ur cases have recognized that the President has

authority to make ‘executive agreements’ with other countries, requiring no ratification by the Senate or approval by

Congress.”); Dames & Moore v. Regan, 453 U.S. 654, 680 (1981); United States v. Belmont, 301 U.S. 324, 330

(1937).

60

See TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra note 11, at 5 (citing U.S. CONST. art. II, § 1, cl. 1

(executive power), § 2, cl. 1 (commander in chief power, treaty power), § 3 (receiving ambassadors)).

61

Garamendi, 539 U.S. at 415; Dames & Moore, 453 U.S. at 680; United States v. Pink, 315 U.S. 203, 229 (1942);

Belmont, 301 U.S. at 330.

62

See TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra note 11, at 88. See also Belmont, 301 U.S. at 330

(continued...)

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 11

If the President enters into a sole executive agreement addressing an area with clear, exclusive

constitutional authority—such as an agreement to recognize a particular foreign government—the

agreement may be legally permissible regardless of congressional disagreement.

63

If, on the other

hand, the President enters into a sole executive agreement and the constitutional authority over

the subject matter is unclear, a reviewing court may consider Congress’s position in determining

whether the agreement is constitutional.

64

If Congress has given implicit approval for the

President’s action or is silent on the matter, courts may be more likely to deem the agreement

valid.

65

When Congress opposes the agreement and the President’s constitutional authority is

ambiguous, it is unclear whether courts would give effect to the agreement.

66

Mixed Sources of Authority for Executive Agreements

Some foreign relations scholars have argued that the international agreement-making practice has

evolved such that some modern executive agreements no longer fit in the three generally

recognized categories of executive agreements.

67

Advocates for a new form of executive

agreements contend that identification of a specific authorizing statute, treaty, or constitutional

power is not necessary if the President already possesses the domestic authority to implement the

executive agreement, the agreement requires no changes to domestic law, and Congress has not

expressly opposed it.

68

In line with this reasoning, the Obama Administration defended its

authority to enter into the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement based, in part, on statutory

authority to implement the agreement, even though existing law did not expressly authorize the

executive branch to conclude new international agreements.

69

Critics of this proposed new

(recognizing constitutional authority for the Litvinov Assignment); Pink, 315 U.S. at 229 (confirming the holding in

Belmont).

63

See THIRD RESTATEMENT, supra note 1, § 303(4). See also Zivotofsky v. Kerry, 135 S. Ct. 2076, 2084–96 (2015)

(recognizing that the Constitution confers the President with exclusive authority to recognize foreign states and their

territorial bounds and striking down a statute that impermissibly interfered with the exercise of such authority).

64

See Dames & Moore, 453 U.S. at 680 (“Crucial to our decision today is the conclusion that Congress has implicitly

approved the practice of claim settlement by executive agreement.”).

65

See id. at 686 (upholding sole executive agreement concerning the handling of Iranian assets in the United States

despite the existence of a potentially conflicting statute given Congress’s historical acquiescence to these types of

agreements). But see Medellín v. Texas, 552 U.S. 491, 531–32 (2008) (suggesting that Dames & Moore analysis

regarding significance of congressional acquiescence might be relevant only to a “narrow set of circumstances,” where

presidential action is supported by a “particularly longstanding practice” of congressional acquiescence).

66

While the exact framework that the Supreme Court would use to evaluate a sole executive agreement that Congress

expressly opposes is not settled, in separation-of-powers cases, the Supreme Court has sometimes adopted the

reasoning of Justice Jackson’s concurring opinion in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, which explained that the

President’s constitutional powers “are not fixed but fluctuate, depending on their disjunction or conjunction with those

of Congress.” 343 U.S. 579, 635 (1952). See also, e.g., Zivotofsky, 135 S. Ct. at 2083, 2096 (citing and relying, in part,

on Justice Jackson’s concurrence). Under Justice Jackson’s framework, the President’s authority could be considered at

its “lowest ebb” when concluding a sole executive agreement in direct opposition to Congress’s expressed will. See

Youngstown Sheet & Tube, 343 U.S. at 637–38. At the “lowest ebb,” the President could conclude a sole executive

agreement only if it fell within a constitutional power that was “at once so conclusive and preclusive” that Congress

cannot regulate the issue. See id.

67

See Harold Hongju Koh, Triptych’s End: A Better Framework to Evaluate 21st Century International Lawmaking,

126 YALE L.J. F. 338, 345 (2017); Daniel Bodansky & Peter Spiro, Executive Agreements+, 49 VAND. J. TRANSNAT’L

L. 885, 887 (2016).

68

See Bodansky & Spiro, supra note 67 at 927; Koh, supra note 67, at 345–48.

69

See DIGEST OF U.S. PRACTICE IN INTERNATIONAL LAW 2012, at 95 (Carrie Lyn D. Guymon ed., 2012). The Obama

Administration made similar arguments concerning its authority to conclude the Paris Agreement on climate change

and the Minamata Convention on Mercury. See CRS Report R44761, Withdrawal from International Agreements:

Legal Framework, the Paris Agreement, and the Iran Nuclear Agreement, by Stephen P. Mulligan, at 18 nn. 145–148;

(continued...)

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 12

paradigm of executive agreements argue that it is not consistent with separation-of-powers

principles, which they contend require that the President’s conclusion of international agreements

be authorized by either the Constitution, a ratified treaty, or an act of Congress.

70

Whether

executive agreements with mixed or uncertain sources of authority become prominent may

depend on future executive practice and the congressional responses.

Choosing Between a Treaty and an Executive Agreement

The changing trends in international agreements has led to debate over whether executive

agreements—particularly congressional-executive agreements—are a constitutionally permissible

alternative to treaties or whether some types of international agreements must be submitted to the

Senate for advice and consent.

71

This debate first surfaced in the mid-20th century when the use

of executive agreements began to rise substantially.

72

The debate was revived in the 1990s when

the United States joined NAFTA and the World Trade Organization through congressional-

executive agreements

73

and when the Obama Administration joined the Paris Agreement on

climate change as an executive agreement.

74

Judicial opinions thus far have not resolved the issue. While the Supreme Court has made clear

that some executive agreements are constitutional,

75

no court has held that executive agreements

are fully interchangeable with treaties. Nor have courts articulated standards to determine what

types of agreements must be submitted to the Senate as treaties and what types of agreements the

President can conclude as executive agreements. There is a dearth of judicial opinions on the

Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of State, United States Joins Minamata Convention on Mercury (Nov. 6, 2013), https://2009-

2017.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2013/11/217295.htm.

70

See Bradley & Goldsmith, supra note 11, at 1263.

71

Compare Bradford C. Clark, Domesticating Sole Executive Agreements, 93 VA. L. REV. 1573, 1661 (2007) (arguing

that the text and drafting history of the Constitution support the position that treaties and executive agreements are not

interchangeable); Laurence H. Tribe, Taking Text and Structure Seriously: Reflections on Free-Form Method in

Constitutional Interpretation, 108 HARV. L. REV. 1221, 1249–67 (1995) (arguing that the Treaty Clause is the exclusive

means for Congress to approve significant international agreements); John C. Yoo, Laws as Treaties?: The

Constitutionality of Congressional-Executive Agreements, 99 MICH. L. REV. 757, 852 (2001) (arguing that treaties are

the constitutionally required form for international agreements concerning action outside of Congress’s Article I

powers, including matters with respect to human rights, political/military alliances, and arms control, but are not

required for Congress’s enumerated powers, such as agreements concerning international commerce); with THIRD

RESTATEMENT, supra note 1, § 303 n.8 (“At one time it was argued that some agreements can be made only as treaties,

by the procedure designated in the Constitution.... Scholarly opinion has rejected that view.”); HENKIN, supra note 22,

at 217 (“[I]t is now widely accepted that the Congressional-Executive agreement is available for wide use, even general

use, and is a complete alternative to a treaty.... ”); Bruce Ackerman & David Golove, Is NAFTA Constitutional?, 108

HARV. L. REV. 799, 861–96 (1995) (arguing that developments in the World War II era altered historical understanding

of the Constitution’s allocation of power between government branches so as to make congressional-executive

agreement a complete alternative to a treaty).

72

See, e.g., WALLACE MCCLURE, INTERNATIONAL EXECUTIVE AGREEMENTS (1941); Edwin Borchard, Shall the

Executive Agreement Replace the Treaty?, 53 YALE L.J. 664 (1944); Myers S. McDougal & Asher Lans, Treaties and

Congressional-Executive or Presidential Agreements: Interchangeable Instruments of National Policy (Pt. I), 54 YALE

L.J. 181 (1945).

73

See, e.g., Ackerman & Golove, supra note 71, at 681–96; Tribe, supra note 71, at 1249–67.

74

Compare, e.g., Steven Groves, The Paris Agreement is a Treaty and Should be Submitted to the Senate,

Backgrounder No. 3103 (Heritage Foundation, March 15, 2016), http://thf-

reports.s3.amazonaws.com/2016/BG3103.pdf (arguing that the Paris Agreement requires the Senate’s advice and

consent) with David A. Wirth, The International and Domestic Law of Climate Change: A Binding International

Agreement Without the Senate or Congress?, 39 HARV. ENVTL. L. REV. 515 (2015) (asserting that neither Senate advice

and consent nor new congressional legislation are necessarily conditions precedent to the United States becoming a

party to an international agreement related to emissions reduction and climate change).

75

See supra note 39.

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 13

issue largely because plaintiffs often cannot satisfy the threshold justiciability requirements that

would allow them to challenge the constitutionality of executive agreements in court.

76

In a

challenge to the President’s ability to join NAFTA outside the Article II treaty-making process,

for example, a U.S. court of appeals concluded that the question of what form an international

agreement should take was a nonjusticiable political question.

77

As a matter of historical practice, some types of international agreements have traditionally been

entered as treaties in all or many instances, including compacts concerning mutual defense,

78

extradition and mutual legal assistance,

79

human rights,

80

arms control and reduction,

81

taxation,

82

and the final resolution of boundary disputes.

83

In addition, the Senate has occasionally used its

76

See Made in the USA Found. v. United States, 242 F.3d 1300, 1319 (11th Cir. 2001), cert. denied, United

Steelworkers v. United States, 534 U.S. 1039 (2001); Greater Tampa Chamber of Commerce v. Goldschmidt, 627 F.2d

258, 265–66 (D.C. Cir. 1980).

77

See Made in the USA Found., 242 F.3d at 1312–19. For background on the political question doctrine, see Cong.

Research Serv., Overview of the Political Question Doctrine, CONSTITUTION ANNOTATED,

https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/artIII-S2-C1-9-1/ALDE_00001283/ (last visited Jan. 25, 2023)

78

See, e.g., Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, Dec. 3, 1948, 62 Stat. 1681, 21 U.N.T.S. 77; North

Atlantic Treaty, Apr. 4, 1949, 63 Stat. 2241, 34 U.N.T.S. 243; Security Treaty, Austl.-N.Z.-U.S., Sept. 1, 1951,

3 U.S.T. 3420; Mutual Defense Treaty, Phil.-U.S., Aug. 30, 1951, 3 U.S.T. 3947; Mutual Defense Treaty, S. Kor.-U.S.,

Oct. 1, 1953, 5 U.S.T. 2368; Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, Sept. 8, 1954, 6 U.S.T. 81; Treaty of Mutual

Cooperation and Security, Japan-U.S., Jan. 19, 1960, 11 U.S.T. 1632, (replacing Security Treaty, Japan-U.S., Sept. 8,

1951, 3 U.S.T. 3329).

79

See generally CRS Report 98-958, Extradition To and From the United States: Overview of the Law and

Contemporary Treaties, by Michael John Garcia and Charles Doyle, at App. A (listing bilateral extradition treaties to

which the United States is a party). Congress enacted statutes that permitted in certain circumstances the extradition of

non-citizens to foreign countries even in the absence of a treaty, Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of

1996, Pub. L. No. 104-132, § 443(a), 110 Stat. 1214, 1280, as well as the surrender of U.S. citizens to face prosecution

before the International Tribunals for Rwanda and Yugoslavia, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year

1996, Pub. L. No. 104-106, § 1342, 110 Stat. 186, 486. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit upheld the

legality of the latter statute and held that extradition may be effectuated pursuant to either a treaty or authorizing

statute. Ntakirutimana v. Reno, 184 F.3d 419, 425 (5th Cir. 1999).

80

See, e.g., Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted Dec. 9, 1948,

78 U.N.T.S. 277 (Agreement was not ratified by Congress until Nov. 5, 1988); International Covenant on Civil and

Political Rights, adopted Dec. 19, 1966, S. EXEC. DOC. NO. E, 95-2, 999 U.N.T.S. 171 (Agreement was not ratified by

Congress until June 8, 1992); Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or

Punishment, adopted Dec. 10, 1984, S. TREATY DOC. NO. 95-2, 1465 U.N.T.S. 85 (Agreement was not ratified by

Congress until Oct. 21, 1994).

81

See, e.g., Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, opened for signature July 1, 1968, 21 U.S.T. 483;

Treaty on the Limitation of Anti-Ballistic Missile Systems, U.S.-U.S.S.R., May 26, 1972, 23 U.S.T. 3435; Convention

on the Prohibition of Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction,

Jan. 13, 1993, S. TREATY DOC. NO. 103-21, 1975 U.N.T.S. 3. But see 22 U.S.C. § 2573 (provision of 1961 Arms

Control and Disarmament Act, as amended, generally barring acts that oblige the United States to limit forces or

armaments in a “military significant manner” unless done pursuant to a treaty or further affirmative legislation by

Congress); Interim Agreement on Certain Measures with Respect to the Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms, U.S.-

U.S.S.R., May 26, 1972, 23 U.S.T. 3462 (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I) Interim Agreement, which was

entered as a congressional-executive agreement, see Pub. L. No. 92-448, 86 Stat. 746, and was intended as a stop-gap,

five-year measure while the parties negotiated a permanent agreement).

82

For a list of tax treaties to which the United States is a party, see United States Income Tax Treaties–A to Z,

INTERNAL REVENUE SERV. (Apr. 28, 2022), https://www.irs.gov/businesses/international-businesses/united-states-

income-tax-treaties-a-to-z.

83

See, e.g., Treaty Concerning the Canadian International Boundary, U.K.-U.S., Apr. 11, 1908, 35 Stat. 2003; Treaty to

Resolve Pending Boundary Differences and Maintain the Rio Grande and Colorado River as the International

Boundary, Mex.-U.S., Nov 23, 1970, 23 U.S.T. 371. The executive branch has regularly entered agreements to

“provisionally” set boundaries pending ratification of a treaty intended to permanently resolve a boundary dispute.

While some of these provisional agreements have been for a short duration, others have remained in effect for many

(continued...)

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 14

conditional consent authority to insist that certain types of agreements be submitted for advice

and consent rather than concluded as executive agreements. In giving advice and consent to

several arms control treaties, for example, the Senate included a declaration that it would consider

“international agreements that obligate the United States to reduce or limit the Armed Forces or

armaments of the United States in a militarily significant manner” only through the Article II

advice and consent process.

84

When giving advice and consent to protocols expanding the North

Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance, the Senate stated that it will not support future

NATO expansion unless the President consults the Senate consistent with the Treaty Clause.

85

State Department regulations also address the dividing line between treaties and executive

agreements. In a process for coordinating and approving international agreements known as the

Circular 175 procedure,

86

the State Department lists criteria for determining whether an

international agreement should take the form of a treaty or an executive agreement. Congressional

preference is one of several factors (identified in the text box below). The Circular 175 procedure

also provides that, in determining how an international agreement “should be brought into force

... the utmost care is to be exercised to avoid any invasion or compromise of the constitutional

powers of the President, the Senate, and the Congress as a whole.”

87

In 1978, the Senate passed a resolution expressing its sense that the President seek the advice of

the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in determining whether an international agreement

should be submitted as a treaty.

88

The State Department later modified the Circular 175 procedure

to provide for consultation with appropriate congressional leaders and committees about

significant international agreements.

89

Consultations are to be held “as appropriate.”

90

Factors to Distinguish Treaties from Executive Agreements

In determining whether a particular international agreement should be concluded as a treaty or an executive

agreement, the State Department requires consideration to be given to these factors:

(1) The extent to which the agreement involves commitments or risks affecting the nation as a whole;

(2) Whether the agreement is intended to affect state laws;

years because of the lack of a ratified final agreement. For example, by way of a series of two-year executive

agreements, the executive branch has continued to provisionally apply a proposed U.S.-Cuba maritime boundary

agreement that was submitted to the Senate in 1978. See SEN. EXEC. DOC. H, 96th Cong.

84

See, e.g., 137 Cong. Rec. 34348 (Nov. 23, 1991) (Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe); 143 Cong. Rec.

932 (Jan. 21, 1997) (Chemical Weapons Convention).

85

See 144 CONG. REC. 7909 (May 4, 1998); 149 CONG. REC. 10783 (May 8, 2003); 163 CONG. REC. S2038 (daily ed.

March 2018); 165 CONG. REC. S5943 (daily ed. Oct. 22, 2019). A paragraph immediately following the consultation

requirement states the following:

The Senate declares that no action or agreement other than a consensus decision by the full

membership of NATO, approved by the national procedures of each NATO member, including, in

the case of the United States, the requirements of Article II, section 2, clause 2 of the Constitution

of the United States (relating to the advice and consent of the Senate to the making of treaties), will

constitute a security commitment pursuant to the North Atlantic Treaty.

E.g., 144 CONG. REC. 7909 (May 4, 1998).

86

Circular 175 initially referred to a 1955 Department of State circular that established a process for the coordination

and approval of international agreements. These procedures, as modified, are now found in 22 C.F.R. Part 181 and

Volume 11 of the Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM). See 11 FAM § 720.

87

11 FAM § 723.3.

88

S. Res. 536, 95th Cong. (1977).

89

11 FAM § 723.4(b)–(c).

90

Id. § 723.4(c).

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 15

(3) Whether the agreement can be given effect without the enactment of subsequent legislation by the

Congress;

(4) Past U.S. practice as to similar agreements;

(5) The preference of the Congress as to a particular type of agreement;

(6) The degree of formality desired for an agreement;

(7) The proposed duration of the agreement, the need for prompt conclusion of an agreement, and the

desirability of concluding a routine or short-term agreement; and

(8) The general international practice as to similar agreements.

Source: 11 FAM § 723.

Non-Binding Instruments

Not every pledge, assurance, or arrangement made between the United States and a foreign party

constitutes a legally binding international agreement.

91

In some cases, the United States makes

non-binding commitments to foreign countries, sometimes called “political commitments” or

“soft law” pacts.

92

Although non-binding instruments do not modify existing legal requirements

under either international or domestic U.S. law, they may still contain commitments with moral

and political weight. For example, the 1975 Helsinki Accords, a Cold War agreement signed by

35 nations, contains provisions concerning territorial integrity, human rights, scientific and

economic cooperation, peaceful settlement of disputes, and the implementation of confidence-

building measures.

93

Under State Department regulations, an international agreement is generally presumed to be

legally binding unless there is an express provision indicating its non-binding nature.

94

State

Department regulations provide that this presumption may be overcome when there is “clear

evidence, in the negotiating history of the agreement or otherwise, that the parties intended the

arrangement to be governed by another legal system.”

95

Other factors considered include the form

of the agreement and its provisions’ specificity.

96

91

See generally Memorandum from Robert E. Dalton on International Documents of Non-Legally Binding Character

1–5 (Mar. 18, 1994), https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/65728.pdf (discussing U.S. and international

practice with respect to non-binding instruments); Duncan B. Hollis & Joshua J. Newcomer, “Political” Commitments

and the Constitution, 49 VA. J. INT’L L. 507 (2009) (discussing the origins and constitutional implications of the

practice of making political commitments); Curtis Bradley et al., The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements: An

Empirical, Comparative, and Normative Analysis, 90 CHI. L. REV. (forthcoming 2023),

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4023641 (discussing increasing use of non-binding instruments for

major international commitments).

92

E.g., Jean Galbraith & David Zaring, Soft Law as Foreign Relations Law, 99 CORNELL L. REV. 735 (2014); CURTIS

A. BRADLEY, INTERNATIONAL LAW IN THE U.S. LEGAL SYSTEM 96 (2d ed. 2015).

93

Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe: Final Act, Aug. 1, 1975, 73 DEP’T ST. BULL. 323, Aug. 1, 1975

[hereinafter Helsinki Accords].

94

22 C.F.R. § 181.2(a)(1) (“In the absence of any provision in the arrangement with respect to governing law, it will be

presumed to be governed by international law.”). See also Hollis & Newcomer, supra note 91, at 525 (“To date, most

(but not all) international lawyers favor a presumption of treaty making in lieu of creating political commitments.”).

95

22 C.F.R. § 181.2(a)(1).

96

Id. § 181.2(a). See also Guidance on Non-Binding Documents, U.S. DEP’T OF STATE, https://2009-

2017.state.gov/s/l/treaty/guidance/index.htm (last visited Jan. 12, 2023). Presidents sometimes unilaterally make

temporary commitments known as modi vivendi arrangements, which are stopgap measures intended to guide the

parties’ conduct until they conclude a more permanent legal agreement. See generally William Hays Simpson, Use of

Modi Vivendi in Settlement of International Disputes, 11 ROCKY MNTN. L. REV. 89 (1938); W. Michael Reisman,

Unratified Treaties and Other Unperfected Acts in International Law: Constitutional Functions, 35 VAND. J.

TRANSNATIONAL L. 729 (2002).

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 16

The executive branch claims authority to make non-binding commitments on behalf of the United

States without congressional authorization, but the scope of this authority is the subject of a long-

standing debate between Congress and the executive branch.

97

Disputes have been particularly

acute when the executive branch has made non-binding commitments involving U.S. military

forces. In 1969, the Senate passed the National Commitments Resolution, expressing the sense of

the Senate that “a national commitment by the United States results only from affirmative action

taken by the executive and legislative branches of the United States government by means of a

treaty [or legislative enactment] ... specifically providing for such commitment.”

98

The resolution

defined a “national commitment” to include “a promise to assist a foreign country ... by the use of

armed forces ... either immediately or upon the happening of certain events.”

99

The National Commitments Resolution, which was a sense of the Senate resolution, had no legal

effect.

100

Although Congress has occasionally considered legislation that would bar significant

military commitments without congressional action,

101

no such measure has been enacted.

Transparency Requirements

To facilitate oversight of and transparency into the United States’ international obligations,

Congress has enacted legislation that requires the executive branch to publish and report to

Congress on certain international commitments.

102

A statute originally enacted in 1950 (1 U.S.C.

§ 112a) requires the Secretary of State to compile and publish annually a list of all treaties and

other binding international agreements in force for the United States.

103

Legislation originally

97

Compare, e.g., Press Briefing by Press Secretary Josh Earnest, WHITE HOUSE (Jan. 29, 2015),

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/01/29/press-briefing-press-secretary-josh-earnest-12915

(“[A] congressional vote on a nonbinding instrument is not required by law and could set an unhelpful precedent for

other negotiations that result in other nonbinding instruments.”); with S. REP. NO. 91-129 (1969) (Senate Committee on

Foreign Relations report criticizing, among other things, the President’s “national commitments” and unilateral pledges

to other countries without congressional involvement).

98

S. Res. 85, 91st Cong. (1969).

99

Id. According to the committee report accompanying the National Commitments Resolution, the resolution arose

from concern over the growing development of “constitutional imbalance” in matters of foreign relations, with

Presidents frequently making significant foreign commitments on behalf of the United States without congressional

action. S. REP. NO. 91-129, at 7 (1969). Among other things, the report criticized a practice it described as

“commitment by accretion,” by which a “sense of binding commitment arises out of a series of executive declarations,

no one of which in itself would be thought of as constituting a binding obligation. Simply repeating something often

enough with regard to our relations with some particular country, we come to support that our honor is involved in an

engagement no less solemn than a duly ratified treaty.” S. REP. NO. 91-129, at 26 (1969).

100

See, e.g., Orkin v. Taylor, 487 F.3d 734, 739 (9th Cir. 2007) (“‘Sense of the Congress’ provisions are precatory

provisions, which do not in themselves create individual rights or, for that matter, any enforceable law.”). For

additional background on “sense of” provisions, see CRS Report 98-825, “Sense of” Resolutions and Provisions, by

Christopher M. Davis.

101

See, e.g., Executive Agreements Review Act, H.R. 4438, 94th Cong. (1975) (proposing to establish legislative veto

over executive agreements involving national commitments); Treaty Powers Resolution, S. Res. 24, 95th Cong. (1977)

(proposing that it would not be in order for the Senate to consider any legislation authorizing funds to implement any

international agreement that the Senate has found to constitute a treaty, unless the Senate has given its advice and

consent to treaty ratification).

102

For background on the development of the transparency regime related to treaties and international agreements, see

TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS, supra note 11, at 209–12; Oona A. Hathaway et al., The Failed

Transparency Regime for Executive Agreements: An Empirical and Normative Analysis, 134 HARV. L. REV. 629, 645–

56 (2020).

103

Several exceptions apply to the publication requirements in the pre-2023-NDAA version of 1 U.S.C. § 112a (2022).

For example, publication is not required when the Secretary of State determines that public interest in the agreements is

insufficient to justify publication. 1 U.S.C. § 112a(b)(2) (2022). The 2023 NDAA replaces these exceptions with a new

(continued...)

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 17

enacted in 1972, commonly called the Case-Zablocki Act (1 U.S.C. § 112b), as amended, requires

the Secretary of State to transmit to Congress the text of all executive agreements to which the

United States is a party within 60 days after the agreement enters into force.

104

Exceptions and

limitations to the Case-Zablocki Act’s requirements

105

led some observers to argue that these

statutes do not provide sufficient insight into international agreement-commitment.

106

To address

potential shortcomings, Congress amended both statutes in the James M. Inhofe National Defense

Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 (2023 NDAA) and created new transparency obligations

that will take effect in September 2023.

107

Qualifying Non-Binding Instruments

The 2023 NDAA will require, for the first time, the executive branch to report and publish certain

non-binding commitments.

108

The 2023 NDAA applies these transparency obligations to

qualifying non-binding instruments, which the statute defines as instruments with foreign

governments, international organizations, or foreign entities (including non-state actors) that

could reasonably be expected to have a significant impact on U.S. foreign policy.

109

A non-

binding instrument that is the subject of a written communication between the Secretary of State

and the chair or ranking member of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs or the Senate

Committee on Foreign Relations is deemed a qualifying non-binding instrument.

110

Instruments

concluded or implemented based on authorities relied on by the Department of Defense (DOD),

the armed forces, or the intelligence community are exempt from the definition of non-binding

instrument.

111

list of agreements and instruments not subject to its transparency requirements. See infra “Congressional Reporting and

Publication Requirements.”

104

The Case-Zablocki Act authorizes the President to decline to transmit executive agreements to the Senate Foreign

Relations Committee and the House Foreign Affairs Committee (then called the House Committee on International

Relations) if, in the President’s opinion, immediate public disclosure of the agreement would prejudice national

security. See 1 U.S.C. § 112b(a) (2022).

105

The notification requirements in the Case-Zablocki Act were not interpreted to apply to every executive agreement.

Legislative history suggests Congress “did not want to be inundated with trivia ... [but wished] to have transmitted all

agreements of any significance.” H.R. REP. NO. 92-301, 92nd Cong. (1972). Implementing State Department

regulations set criteria for assessing when a compact constitutes an “international agreement” that must be reported

under the Case-Zablocki Act. These regulations provide that “[m]inor or trivial undertakings, even if couched in legal

language and form,” are not considered to fall under the purview of the act’s reporting requirements. 22 C.F.R.

§181.2(a).

106

See Hathaway et al., supra note 102, at 657–91.

107

2023 NDAA, § 5947 (to be codified at 1 U.S.C. §§ 112a–112b).

108

The State Department’s pre-2023-NDAA regulations on publication and reporting of international agreements do

not apply to non-binding documents. See 22 C.F.R. § 181.2(a)(1). On at least one occasion, Congress enacted context-

specific legislation requiring the executive branch to provide notification of any commitment, regardless of whether it

was legally binding, so that Congress could give expedited consideration on whether to disapprove of the commitment.

See Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015, Pub. L. No. 114-17, § 2(h)(1), 129 Stat. 201, 211 (codified in 42

U.S.C. § 2160e(h)(1)).

109

2023 NDAA, § 5947(a)(1) (to be codified at 1 U.S.C. § 112b(k)(5)(A)).

110

Id.

111

Id. (to be codified at 1 U.S.C. § 112b(k)(5)(B)). Some observers argue that, because DOD concludes a high volume

of non-binding instruments, the exemption for instruments based upon DOD, armed forces, and intelligence authorities

will have the effect of excluding many non-binding instruments from the 2023 NDAA’s disclosure requirements. See

Curtis Bradley, Jack Goldsmith, Oona Hathaway, Congress Mandates Sweeping Transparency Reforms for

International Agreements, LAWFARE (Dec. 23, 2022), https://www.lawfareblog.com/congress-mandates-sweeping-

transparency-reforms-international-agreements.

International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law

Congressional Research Service 18

Congressional Reporting and Publication Requirements

Once in effect, the 2023 NDAA will require the Secretary of State to provide monthly written

reports to the majority and minority leaders of the House and Senate and of the foreign affairs

committees with the material listed in the text below.

Congressional Reporting Requirements in the 2023 NDAA

Under the 2023 NDAA, the Secretary of State must provide the following each month:

List: A list of all international agreements

112

and qualifying non-binding instruments signed, concluded, or

otherwise finalized or that entered into force or became operative in the prior month.

113

Text: The text of each agreement and instrument, including any implementing material, annex, appendix, side

letter, or similar document entered into contemporaneously and in conjunction with the underlying agreements

and instruments.

114

Authorizing authority: A detailed description of the legal authority that the executive branch views as

authorizing the agreements and instruments.

115

All citations to the Constitution, treaties, and statutes must

include the specific article, section, or subsection that the executive branch relies upon.

116

If the relied-upon

authority includes Article II of the Constitution, the executive branch must explain the basis for its reliance.

117

Implementing authority: A statement of any new or amended statutory or regulatory authority anticipated to

be necessary to implement a listed agreement or instrument that entered into force or became operative.

118

Along with periodic reports to Congress, the 2023 NDAA will require the Secretary of State to

publish the text, authorizing authority, and implementing authority for each international

agreement and qualifying non-binding instrument on its website within 120 days of entering into

force or becoming operative.

119

The legislation will exempt several categories of agreements and

instruments from this publication requirement.

120

Exempted agreements and instruments are those