Briefing

March 2017

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

Authors: Micaela Del Monte and Elena Lazarou

EPRS - EP Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

EN

PE 599.381

How Congress and President shape

US foreign policy

SUMMARY

The United States Constitution regulates the conduct of American foreign policy

through a system of checks and balances. The Constitution provides both Congress

and the President, as the legislative and executive branches respectively, with the

legal authority to shape relations with foreign nations. It recognises that only the

federal government is authorised to conduct foreign policy; that federal courts are

competent in cases arising under treaties; and declares treaties the supreme law of

the land. The Constitution also lists the powers of Congress, including the 'power of

the purse' (namely the ability to tax and spend public money on behalf of the federal

government), the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, the power to

declare war and the authority to raise and support the army and navy. At the same

time, the President is the Commander-in-Chief of the United States (US) army and

navy and, although Congressional action is required to declare war, it is generally

agreed that the President has the authority to respond to attacks against the US and

to lead the armed forces. While the President’s powers are substantial, they are not

without limits, due to the role played by the legislative branch.

In light of the discussion of the foreign policy options of the new administration under

President Donald Trump, this briefing specifically explores the powers conferred to

conclude international agreements, to regulate commerce with foreign nations, to

use military force and to declare war. It also explains how Congress performs its

oversight – or ‘watchdog’ – functions with regard to foreign policy, the tools at its

disposal, and the role of committees in the process.

In this briefing:

Executive and legislative roles in the US

Constitution

Concluding international agreements

Regulating commerce with foreign

nations

Declaring war and the use of military

force

Congressional oversight of foreign

policy

Main references

Annex

EPRS

How Congress and President shape US foreign policy

EPRS - European Parliament Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

Page 2 of 12

Executive and legislative roles in the United States Constitution

The United States (US) Constitution establishes a broad scenario for developing relations

with other countries and leaves the government branches to set precedents. Generally,

the Constitution regulates the conduct of American foreign policy by subjecting it – like

all federal power – to a system of checks and balances. Consequently, observers of

geopolitical strategy followed the 2016 presidential election closely, while the

Congressional election proceeded relatively unnoticed. However, while the President’s

powers are particularly substantial, they are not without limits. The President does not

make decisions in a vacuum, but in a context where the legislative branch has its own role

to play. The Constitution provides the legal authority to both Congress, the legislative

branch and the President, the executive branch, to shape relations with foreign nations;

it recognises that only the federal government – not

the states – is authorised to conduct foreign policy,

and that federal courts are competent in cases arising

under treaties; it declares treaties the supreme law of

the land.

The Constitution also lists the powers of Congress,

including the ‘power of the purse’ (i.e. the ability to

tax and spend public money on behalf of the federal

government), the power to regulate commerce with

foreign nations, the power to declare war, and the

authority to raise and support the army and navy. The

President is the Commander-in-Chief of the US army

and navy, and although Congressional action is

required to declare war, it is generally agreed that the

President has the authority to respond to attacks

against the US, and to lead the armed forces. In the

course of American history, Congress has declared war

five times against 11 nations,

1

and has authorised the

use of military force on other occasions, as was the

case against Iraq in 2002.

The President also has the legal authority to make

treaties, and appoint Ambassadors, subject to Senate advice and consent, as well as the

authority to receive Ambassadors and other public ministers. While primary

responsibility for entering into international agreements lies with the President, these

agreements are often not self-executing. They therefore require congressional

implementing legislation to give US authorities the domestic legal authority required to

enforce and implement the agreement. The President is the nation’s chief diplomat, and

the State Department acts as the President’s executive agency in the conduct of

diplomatic action. The State Department’s mission includes, among other things, the

preservation of US national security; the promotion of world peace; respect of the rule of

law and human rights; and cooperation in international trade organisations. While the

Secretary of State does not originate foreign policy, the office-holder is the President’s

principal foreign policy adviser and as such is expected to conduct diplomacy and

coordinate and implement government policies affecting other countries.

Finally, Congress can use its oversight role to question and influence policy choices, in

particular, during the annual procedure to authorise and allocate funds for the agencies

Congress and President shaping foreign

policy cooperatively

In June 1947, Secretary of State

George C. Marshall proposed US help for

European recovery, on the condition that

the European states initiate and agree on

plans for aid programmes. Western

European governments proposed a

programme based on four years of US

assistance. President Harry S. Truman

requested an interim aid programme,

which was approved by Congress in 1947;

subsequently submitting a longer term

European Recovery Program to Congress.

This operation allowed Congress sufficient

time to hold hearings and create a Select

Committee on Foreign Aid that carried out

an independent study on Europe needs.

The final legislation for the Marshall Plan

from 1948 was considered the product of

a joint effort by both branches of

government.

EPRS

How Congress and President shape US foreign policy

EPRS - European Parliament Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

Page 3 of 12

responsible for foreign policy. Through hearings, investigations and subpoenas

2

Congress

monitors policy developments, and holds the President accountable. One of the most

recent investigations looked into the circumstances surrounding the 2012 attacks on the

US consulate in Benghazi, leading to the death of the US Ambassador to Libya and one US

information officer.

Concluding international agreements

In the United States, the term 'international agreement' pools two major types of

agreements: international treaties and executive agreements.

3

In setting its foreign

policy priorities, the administration may decide to begin negotiations with a country,

withdraw from, or renegotiate, existing international agreements. For instance,

President Trump expressed a clear intention to renegotiate the NAFTA agreement, and

issued a Memorandum directing the US Trade Representative (USTR) to withdraw the US

from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

According to US law, a treaty is an international agreement whose entry into force with

respect to the US requires two-thirds of the Senate to give advice and consent, as well as

Presidential ratification, acting as Chief Diplomat of the US.

4

Once ratified, a treaty

becomes the supreme law of the land,

5

although a distinction should be made between

self-executing treaties and non-self-executing treaties, which require implementing

legislation.

6

The US government has broad powers to enter into treaties with foreign

countries. Indeed, according to the US Supreme Court, Article 6 of the US Constitution

confers a treaty power on the US, which ‘extends to all proper subjects of negotiation

between our government and the governments of other nations ... as it is not perceived

that there is any limit to the questions which can be adjusted touching any matter’.

7

For

the first century of US history, around half of all international agreements were made

under the constitutional provision of Article 2,

8

however, from the 1940s, the ratio of

executive agreements rose to 94 %. This shift may have occurred due to a necessity to

respond to the complex and extremely challenging international context, which often

requires rapid action. It may also have resulted de facto, as a progressive erosion of

congressional prerogatives, to the benefit of presidential powers.

How Article 2 treaties are concluded

The Constitution gives both the Senate and President a share of treaty power. This

ensures that the Senate can check presidential power and safeguard the sovereignty of

the states by giving each of them an equal vote in the treaty making process. The process

of concluding Article 2 treaties comprises a number of steps: negotiation, signature,

Senate consideration, Senate advice and consent, and finally presidential ratification.

Negotiation and conclusion: While negotiating is a sole presidential prerogative,

9

informal Senate involvement, or at least consultation, during negotiations is often

ensured, although not formalised. The practice probably developed to guarantee formal

Senate advice and consent at a later stage. The President is also responsible for signing

the treaty, signalling that negotiators have reached an agreement, and that the US

consents to be bound, once the treaty is ratified.

Consideration by Senate Committee: Following signature, the President may submit a

treaty to the Senate for advice and consent. The transmission is accompanied by a

presidential message including a detailed description of treaty provisions. The treaty is

referred to the Committee on Foreign Relations and placed on the committee calendar.

Although the committee is not bound to take any action, if it decides to do so; it may hold

EPRS

How Congress and President shape US foreign policy

EPRS - European Parliament Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

Page 4 of 12

hearings, and invite experts and the administration to provide information related to the

treaty. The committee may subsequently present the treaty to the full Senate, or return

it to the President. In reporting to the full Senate, the committee proposes a resolution

of ratification. Often, a treaty is reported with no conditions, but the Committee may also

recommend that the Senate adopt the treaty under certain conditions.

10

If these

conditions alter the nature of the treaty, requiring the reopening of negotiations, the

President must communicate the conditions to the other treaty parties.

Consideration and vote by the full Senate: The full Senate votes on the treaty, following

consideration of the resolution of ratification as proposed by the Committee on Foreign

Relations. The vote requires the agreement of two thirds of the Senators present. Should

the vote fail, the treaty may be returned to the committee or to the President.

Ratification: Should the vote be successful, the President decides whether or not to ratify.

The ratification process consists of the President signing and sealing an instrument of

ratification, which is then exchanged with the treaty counterpart. Following this

exchange, the President issues a proclamation declaring the treaty’s entry into force.

During the Obama Administration’s two terms, 34 treaties were approved by the Senate

(on extradition, mutual legal assistance, tax convention, and defence trade cooperation,

among other things), while 109 treaties were approved under the two terms of the

George W Bush Administration preceding it.

Article 2 treaties versus executive agreements

Article 2 treaties are not the only way to conclude international agreements. Under US

law, international agreements can be brought into force on a different legal basis than

Senate advice and consent. These are known as executive agreements,

11

which can be

concluded on the basis of:

(1) existing legislation, or subject to subsequent

legislation to be enacted by both chambers of

Congress (known as Congressional executive

agreements). In this case, Congressional authorisation

is given in the form of a statute passed by both

chambers. The most common use of these types of

agreements is in international trade, where

Congressional legislation authorises the President to

negotiate and enter into agreements to reduce tariffs

or other impediments to international trade;

(2) existing agreement (known as treaty executive

agreements). For example, the US-Japan Migratory

Birds Convention of 1972 establishes that new species

may be added to the list of protected species by a simple exchange of diplomatic

notes;

(3) sole presidential authority, without seeking legislative branch approval (known as

presidential or sole executive agreements). It is argued that on this basis,

presidential authority is limited to specific cases. The President, as Commander-in-

Chief and Chief Diplomat, could conclude armistice agreements as well as certain

agreements incidental to the operation of foreign embassies in the form of sole

executive agreements. One of the best-known sole executive agreements was

concluded between the US and Iran to solve the Iran hostage crisis, known as the

‘Algiers Accords’, in 1981. Although limited in scope, these agreements may have

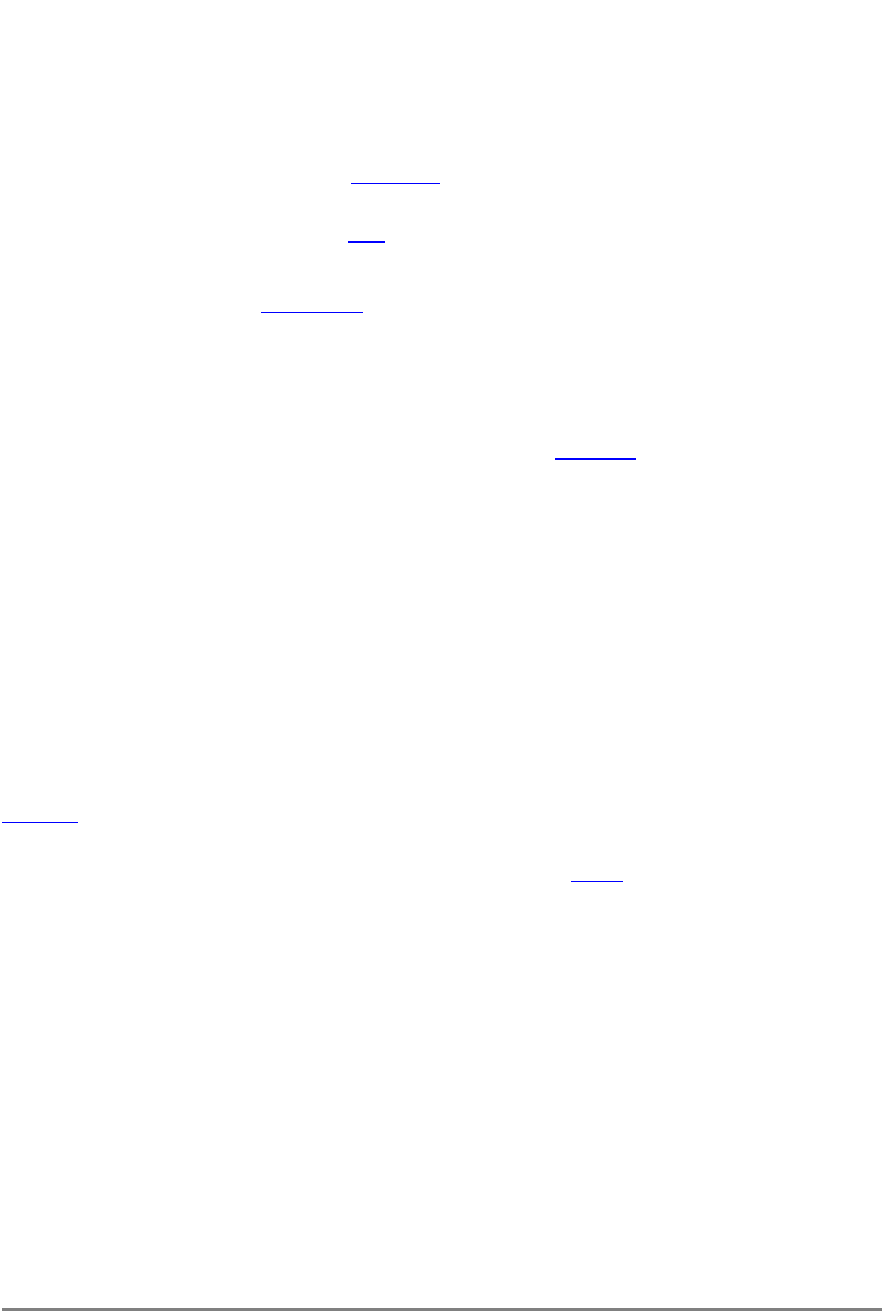

Types of international agreements

Article II Treaties, with Senate

advice and consent

Congressional executive

agreements, requiring

legislation by Congress

with prior congressional

approval

with subsequent approval of

Congress

Treaty executive agreements

Presidential or sole executive

agreements

EPRS

How Congress and President shape US foreign policy

EPRS - European Parliament Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

Page 5 of 12

considerable consequences in political terms, such as the Litvinov Agreement in 1933

regarding American recognition of the Soviet Union, the ‘destroyers for Bases

Exchange’ with the United Kingdom in 1940,

12

or the Yalta Agreement in 1945.

Regardless of the type of executive agreement, if budget outlay is required, Congress is

involved, due to its ‘power of the purse’.

How to determine the type of agreement

Appendix A of the State Department C-175 Handbook,

13

lists a number of elements to be

considered by the administration, notably:

the commitments and risks involved into the agreement;

possible effects on state law;

past practice in similar cases;

necessity to enact law to give effect to the agreement;

Congress preferences;

proposed duration, and the degree of urgency required to conclude.

These criteria are meant to guide the administration rather than undermine the exercise of

presidential discretion. Indeed political considerations may also play a role.

How to terminate international agreements

Terminating international agreements has to be approached from two different legal

contexts; international law and US domestic law. According to international law, a party

may withdraw from an agreement either in accordance with the terms of the agreement

(usually termination by notice), or, in the absence of specific provisions, in accordance

with the Vienna Convention of 1969.

14

Breach of the treaty by one of the parties or by

agreement of all the involved parties may also result in termination of an agreement.

Under US domestic law, the first element to note is that the US Constitution contains no

specific provision for withdrawal from international agreements, indeed Article 2 only

sets a procedure for the President and Senate to make treaties. As Article 6 of the US

Constitution recognises treaties as the law of the land, with the same domestic status as

federal law, it is assumed that US participation could be terminated if Congress passes a

subsequent statute which is inconsistent with the terms of an existing international

agreement. In this case, however, only domestic law would be affected, while

international obligations would remain unchanged. Practice has been inconsistent over

the years, indeed, international agreements have been terminated by the:

President following Congress authorisation or direction (for instance direction

mandating termination by notice of the President);

President with subsequent congressional approval;

President following Senate authorisation or direction;

President with subsequent Senate approval;

President alone.

Such inconsistency, and the absence of clear legislative norms, raises academic questions,

and disputes between the legislative and executive. The debate has focused mainly on

the President’s unilateral authority to terminate international agreements, but some

observers have also looked at the possibility for Congress to terminate agreements

without presidential support. Reasonable arguments have been put forward to explain

why the authority to terminate an agreement should be vested in the President alone, in

the President with the Senate, or in Congress. A CRS study suggests that the President

alone has the authority to terminate international obligations, as regardless of the

EPRS

How Congress and President shape US foreign policy

EPRS - European Parliament Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

Page 6 of 12

domestic approval procedure, the President alone consents on behalf of the United

States and has ‘plenary and exclusive [power] … as the sole organ of the Federal

Government in the field of international relations’.

15

For instance, in 1979, President

Jimmy Carter terminated the Mutual Defence Treaty with Taiwan unilaterally. The judicial

branch, traditionally reluctant to clarify the issue, dismissed the subsequent case on

‘political question’

16

grounds (i.e. the challenge was considered a political, rather than a

judicial, question). More recently, in 2002, President George W. Bush terminated the

Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty with Russia, and the district court also declared this case

unsuitable for resolution in the court, due to the ‘political question’.

17

Paris Agreement

During the 2016 presidential debate, President Donald Trump questioned the US commitment to

a transition to a low-carbon economy and threated to 'withdraw from the Paris Agreement'. The

US became a signatory party to the Paris Agreement in April 2016, by signature of the Secretary

of State. Subsequently, President Barack Obama signed the Agreement’s instrument of

acceptance, and the US became party to the Agreement upon its entry into force in

November 2016. This was considered an executive agreement and not a treaty. The issue of which

provisions to make binding was a central concern for the Obama administration, so that the

President could accept the agreement without seeking Senate advice and consent. Additionally,

Congress enacted no implementing legislation, and the administration did not declare that its

provisions were self-executing. From an international law perspective, Article 28 of the Paris

Agreement specifies that a party may notify its intention to withdraw three years from the date

on which the agreement entered into force for the given party, to take effect one year from the

date of notification.

18

This four year period could be reduced to one should the US decide to

withdraw from the 1992 United Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Indeed, the Paris Agreement states that withdrawal from the UNFCCC shall also be considered as

withdrawal from the Agreement, even though the UNFCCC was considered a treaty and received

Senate advice and consent. Thus, under US domestic law, it is unclear what role Congress should

play in termination of the Agreement. Finally, even without formal withdrawal, the new

administration would appear to have the option to undermine Paris Agreement objectives by

refusing to implement some of its provisions.

Regulating commerce with foreign nations

While the President retains the power to make treaties, Congress has the authority to

regulate commerce with foreign nations, and may exercise its power in other ways, from

oversight on international trade policies and programmes to implementing legislation on

international trade matters. Although many committees may be involved, depending on

their specific jurisdiction, in Congress the primary responsibility for trade matters rests

with the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee. To

reaffirm Congress’s overall constitutional role in initiating and overseeing US trade policy,

Congress has enacted Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation. Also known as ‘fast-

track’, TPA is an expedited procedure that allows Congress to implement trade

agreements, providing that the administration fulfils the negotiating objectives and

respects certain requirements on notification to and consultation with Congress. In

general, expedited procedures may establish time for floor scheduling of bills, limit

debate in committees and/or limit the possibility to offer (i.e. table) amendments. In the

specific case of trade, the modern form of TPA, introduced in 1974, establishes, among

other things, automatic discharge from committee, limited floor debate, and an ‘up or

down’ vote without amendments. This latter is an important element in trade

negotiations, as foreign nations may be confident that the negotiated agreement with

the executive will not be amended by the legislative branch. Finally, TPA establishes the

EPRS

How Congress and President shape US foreign policy

EPRS - European Parliament Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

Page 7 of 12

process for Congress to withdraw the expedited procedure to an implementing bill,

should it consider that TPA requirements have not been fulfilled. In such a case, the

implementing bill would be considered under the general rules of procedures, with

Congress enabled to offer amendments. The United States is party to 14 international

free trade agreements (FTAs) with 20 countries and is also negotiating a Trans-Atlantic

Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the European Union.

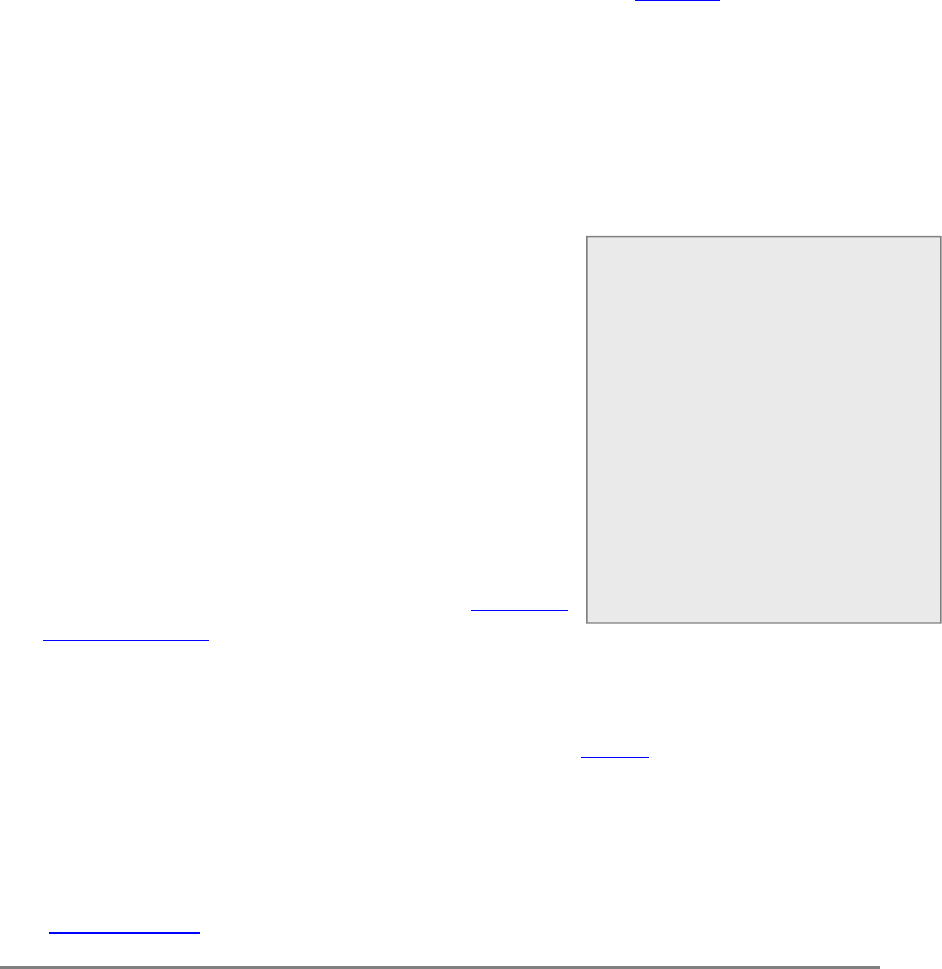

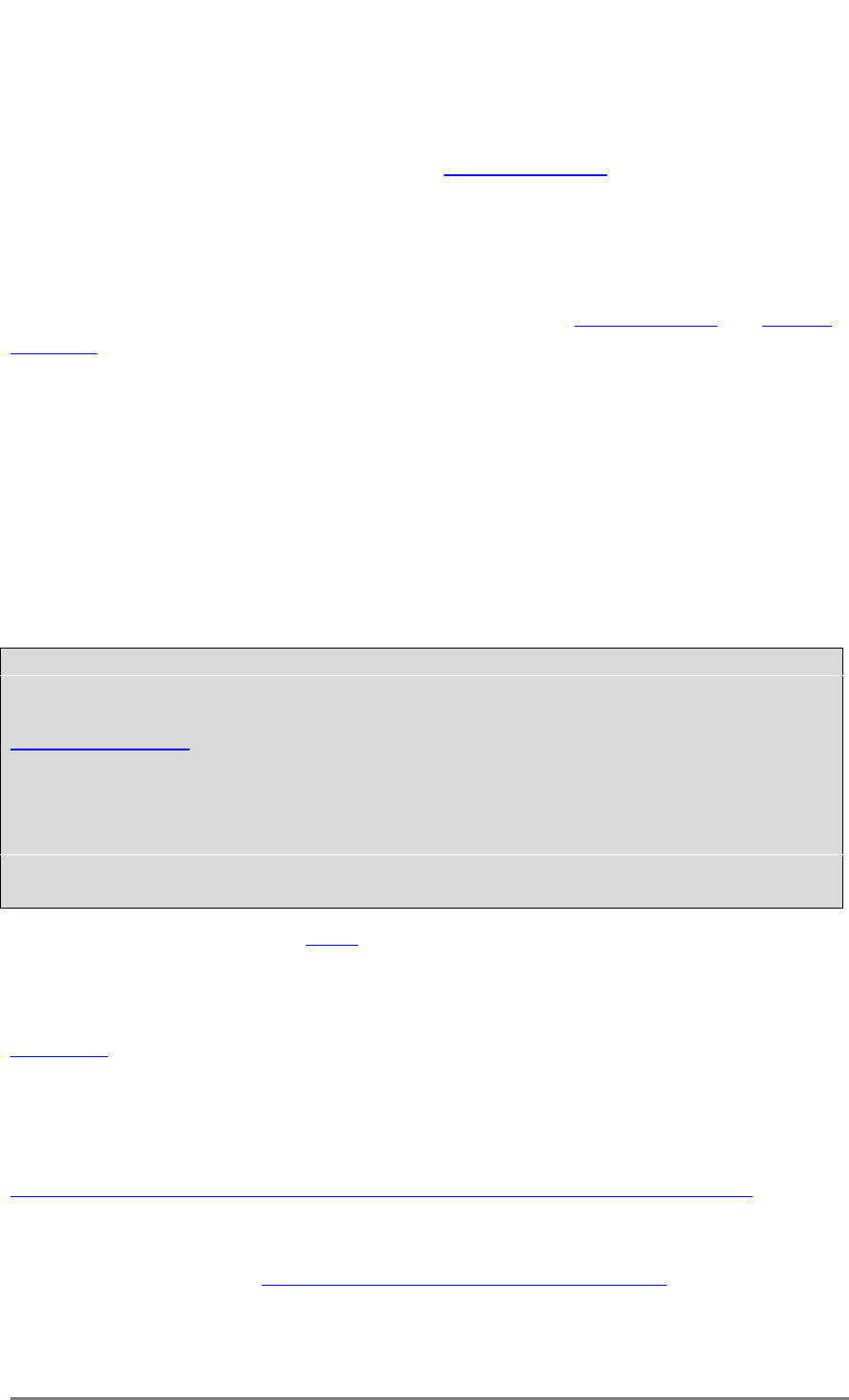

Figure 1 – United States' free trade agreements

Source: CRS, International Trade and Finance: Overview and Issues for the 115th Congress,

21 December 2016.

Regulating tariffs

During the 2016 presidential campaign, President Trump mentioned unilateral

withdrawal from a number of trade agreements, but also the possibility of imposing high

tariffs (for example, on Mexico and China). The US Constitution vests the power to impose

and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, in Congress – and not in the President.

Nevertheless, since the 1930s, Congress has adopted legislation to delegate authority to

the President to reduce tariffs and has conferred other powers related to trade on the

President.

19

A recent CRS report provides a non-exhaustive list of statutes that would

authorise the administration to impose tariffs and/or quotas or regulate commerce.

Although the wording of the statutes, as well as the presidential powers and the

conditions are inconsistent, the report mentions that most of the acts accompany the

delegation of powers with conditions and time limits (see Annex I).

Declaring war and the use of military force

The Constitution divides powers pertaining to warfare between Congress and the

President. Article 1, Section 8 grants Congress the power to declare war, while Article 2,

Section 2, authorises the President, as Commander-in-Chief, to lead all the armed forces.

Thus, while Congress makes decisions regarding the declaring and funding of an

operation, the President directs it.

While it is generally agreed that, as Commander-in-Chief, the President has the power to

utilise the armed forces as the President deems necessary when the US faces an attack,

presidential authorisation to deploy forces (US troops) abroad without congressional

EPRS

How Congress and President shape US foreign policy

EPRS - European Parliament Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

Page 8 of 12

authorisation or a declaration of war (which, as explained above, is a congressional

power) has been controversial. While Presidents have, de facto, used their authority to

send US troops into combat or into situations of imminent hostilities in the past, this

remains an issue of concern today.

The issue of presidential use of armed forces without congressional authorisation was

addressed in the 1973 War Powers Resolution, which was passed by Congress overriding

the veto of President Richard Nixon. The resolution aimed at establishing procedures for

both the executive and legislative branch to share decisions regarding involvement in war

or deployment of US armed forces in hostile situations. Under this law, the President

must:

consult with Congress before sending US troops into hostile situations;

report commitment of US forces to Congress within 24 hours;

end military action within 60 days if Congress does not declare war or authorise

the use of force.

According to the Congressional Research Service, from 1975 to 2012, presidents have

submitted more than 130 reports related to deployment of US forces, as required by the

resolution. However, only a single occasion, the 1975 Mayaguez incident, cited action

triggering the sixty-day time limit.

Congress retains the ‘power of the purse’ when it comes to the approval, modification or

rejection of defence spending (the Department of Defense budget). The National Defense

Authorization Act (NDAA) is an annual federal law specifying the Department of Defense

budget and expenditures. It advances the vital funding and authorities that America’s

military requires. In addition, Congress oversees the defence budget primarily through

defense appropriations bills.

Experts argue that powers related to warfare remain ‘spelled out more clearly for

Congress but in practice are dominated by presidential action’.

Contribution to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

During his campaign, and as President-elect, Donald Trump criticised NATO as 'obsolete', leading

to speculation that he would consider decreasing US contributions to the alliance. However, in

his first presidential address to Congress, on 28 February 2017, President Trump said his

administration ‘strongly supports’ NATO, but reiterated his appeal to ‘partners to meet their

financial obligations’. However, US participation in NATO is also subject to congressional

approval, as it is directly linked to budgetary approval. For example, in 2015, the Obama

administration requested, and Congress appropriated, about US$1 billion for a new European

Reassurance Initiative (ERI) in the Department of Defense (DOD) Overseas Contingency

Operations account. This was a contribution to increased US military activities under Operation

Atlantic Resolve. In 2016, the administration requested, and received, US$789.3 million for ERI.

The ERI aims at enhancing US military activities, including increased military presence in Europe;

additional bilateral and multilateral exercises, and training with allies and partners; enhanced

prepositioning of US equipment; and intensified efforts to build partner capacity for newer NATO

members and other partners. In its proposed budget for the 2017 financial year, the Obama

administration requested US$3.4 billion (a fourfold increase) in funding for the ERI, primarily to

enable ‘a quicker and more robust response in support of NATO’s common defence’. The 2017

budget is currently funded with a stop-gap measure. When a full budget is passed (possibly in

April 2017), Congress’s response to the request will be clearer. President Trump’s proposed

budget for 2018 increases defence spending by US$54 million.

EPRS

How Congress and President shape US foreign policy

EPRS - European Parliament Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

Page 9 of 12

Congressional oversight of foreign policy

Congress has the constitutional power to scrutinise, and the authority to promote, a

democratically accountable foreign policy. In doing so, Congress informs public opinion

about presidential use of force, global strategic choices, and federal spending priorities,

and ensures that the administration does not depart from congressional intent. In this

respect, mention should also be made of the Case-Zablocki Act of 1972, also known as

the Case Act, which requires the Secretary of State to transmit to Congress all

international agreements other than treaties no later than 60 days after their entry into

force.

20

A recent book

21

by Linda L. Fowler, Professor of Government at Dartmouth College, looks

at the formal public hearings of the two Senate Committees (Armed Services and Foreign

Relations) from 1947 to 2008, to assess whether or not Congress was effective in

performing its scrutiny of international affairs.

22

The analysis concludes that, although

congressional involvement in foreign policy is important, it has multiple motivations and

not always aligned goals. Congress is often driven by crises and perceived threats to

national interests, but contrary to possible expectations, oversight does not only happen

in times of divided government (i.e. to maintain the constitutional remit of the executive).

For instance, in 2004, the Senate conducted public hearings on the Iraq War and

investigated abuse of detainees at Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib Prison. The number of hearings

only increased when Democrats took control of Congress in 2007. Fowler argues for a

reassessment of congressional powers on war, and proposes reform to encourage Senate

watchdogs to improve public deliberation on decisions of war and peace.

The Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe – The Helsinki Commission

Congressional oversight on foreign policy can sometimes be achieved through a specific

approach. In 1976, the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, also known as the

Helsinki Commission, was created to promote human rights, military security, and economic

cooperation in Europe, Eurasia, and North America. The Commission, which is an independent US

government agency, counts 21 commissioners: nine members from the Senate, and nine from

the House of Representatives (five from the majority and four from the minority in both

chambers), who serve for the duration of the Congress from which they are appointed. Three

commissioners come from the executive branch and are appointed by the President: one each

from the Department of State, the Department of Defence, and the Department of Commerce.

Several foreign policy experts argue that presidents have accumulated power at the

expense of Congress in recent years, especially during times of war or national

emergency. They attribute this to the spirit and wording of the Constitution itself, and to

the reluctance of the judicial branch to clarify foreign policy related questions. Most

academics seem to concur that congressional oversight is a key element to maintaining

balance in the shaping of US foreign policy.

Main references

E. Chemerinsky, Constitutional Law, Principles and Policies, 4th edition, Wolters Kluver, 2011.

Treaties and other International Agreements: The role of the United States Senate, a study

prepared for the Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate by the Congressional

Research Service, January 2001.

G. S. Krutz and J. S. Peake, Treaties and Executive Agreements: A History, The University of

Michigan Press, 2009.

EPRS

How Congress and President shape US foreign policy

EPRS - European Parliament Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

Page 10 of 12

M. J. Garcia, International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law, CRS,

18 February 2015.

R. F. Grimmett, War Powers Resolution: Presidential Compliance, CRS, 25 September 2012.

Endnotes

1

1812 war with Great Britain, 1846 war with Mexico, 1898 war with Spain, 1971 World War I with Germany and

Hungary, 1941 World War II with Japan, Germany, Italy, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania.

2

Subpoena power is defined as the ‘authority granted to House and Senate committees by the rules of their

respective houses to issue legal orders requiring individuals to appear and testify, or to produce documents

pertinent to the committee’s functions, or both’.

3

According to a 2015 CRS report, over 17 300 executive agreements have been concluded by the US since 1939 (out

of 18 500 since 1789) compared to 1 100 treaties that have been ratified by the US.

4

The article reads: ‘He shall have power, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, to make treaties, provided

two thirds of the Senators present concur’.

5

Whitney v. Robertson, 1888. ‘Both statues and treaties are declared to be the supreme law of the land, and no

superior efficacy is given to either over the other’.

6

In the latter, more precisely, it is the legislation, not the treaty, which becomes law of the land.

7

Geofroy v. Riggs, 1890.

8

G. Krutz and J. Peake: Treaty Politics and the Rise of Executive Agreements International commitments in a System

of Shared Powers, University of Michigan Press, 2009, p. 24.

9

United States v. Curtiss–Wright Export Corp, 1936.

10

A 2001 CRS report lists four main types of conditions: 1) Amendments, requiring the consent of the other treaty

parties; 2) Reservations changing US obligations thus also requiring the consent of the other treaty parties;

3) Understanding clarifying and interpreting the text without modifying it; 4) Declarations expressing Senate

position on a given issue.

11

Executive Agreements can be used for any purpose, meaning that anything that can be done by treaty can be done

by executive agreement.

12

In 1940, thanks to the Destroyer-Bases Agreement, President Roosevelt extended American involvement in World

War II. The US agreed to loan the United Kingdom 50 naval destroyers, and the US obtained 99 year free leases to

develop military bases in Caribbean and Newfoundland locations in exchange.

13

Article 721.3 Appendix A, The Handbook on Treaties and Other International Agreements (The C-175 Handbook),

US Department of State.

14

Although the US has not ratified the Vienna Convention, in many aspects, it is considered to reflect customary

international law.

15

United States v. Curtiss–Wright Export Corp, 1936.

16

Goldwater v. Carter, 1979. Several members of Congress challenged the President’s right to drop out of the mutual

defence agreement with Taiwan and went to court. While the Court of Appeal stated that unilateral presidential

action was sufficient to terminate a treaty, four Justices of the Supreme Court found the case non justiciable. See

Baker v. Carr, 1962, in particular Justice Curtis’ opinion.

17

Kucinich v. Bush, 2002.

18

J. A. Leggett, R. K. Lattanzio, Climate Change: Frequently Asked Questions about the 2015 Paris Agreement, CRS,

5 October 2016.

19

In these cases, presidential actions under this delegated authority may be challenged in court, to check whether the

delegation of powers was constitutional or whether the President acted within the scope of the powers specifically

delegated by Congress.

20

Should the President consider the disclosure of an executive agreement prejudicial to the US security, the act will

be transmitted to the Senate Foreign Relations and House International Relations Committees with a security

classification.

21

L. L. Fowler, Watchdogs on the hill, the decline of congressional oversight of U.S. foreign relations, Princeton

University Press, 2015.

22

Together the Senate Armed services and Foreign Relations Committees conducted 3 257 public hearings and 2 124

executive sessions for a total of 5 381 observations and 11 276 formal hearing days.

EPRS

How Congress and President shape US foreign policy

EPRS - European Parliament Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

Page 11 of 12

Disclaimer and Copyright

This document is prepared for, and addressed to, the Members and staff of the European Parliament as

background material to assist them in their parliamentary work. The content of the document is the sole

responsibility of its author(s) and any opinions expressed herein should not be taken to represent an official

position of the Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

© European Union, 2017.

Photo credits: © assetseller / Fotolia.

http://www.eprs.ep.parl.union.eu (intranet)

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank (internet)

http://epthinktank.eu (blog)

EPRS

How Congress and President shape US foreign policy

EPRS - European Parliament Liaison Office, Washington DC; Members’ Research Service

Page 12 of 12

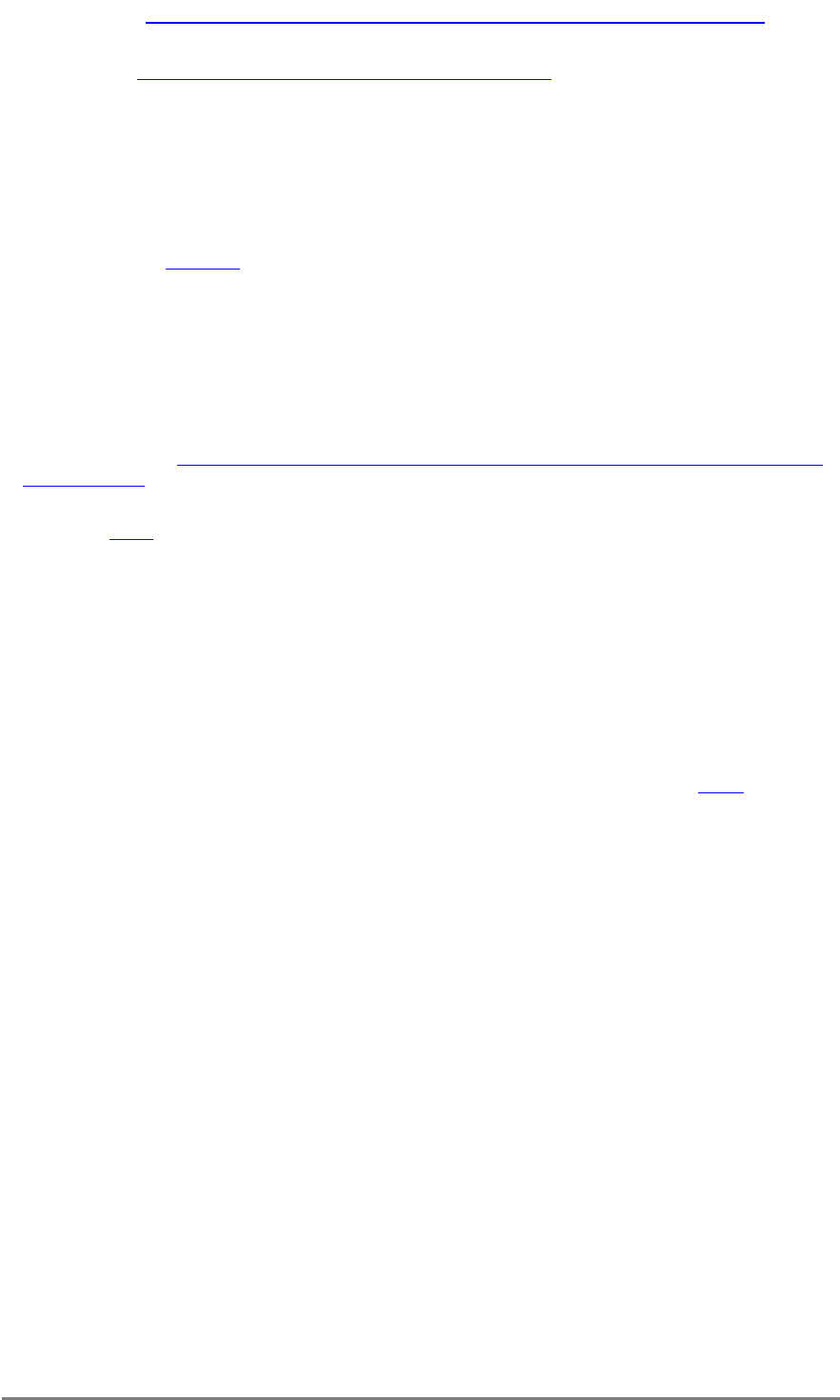

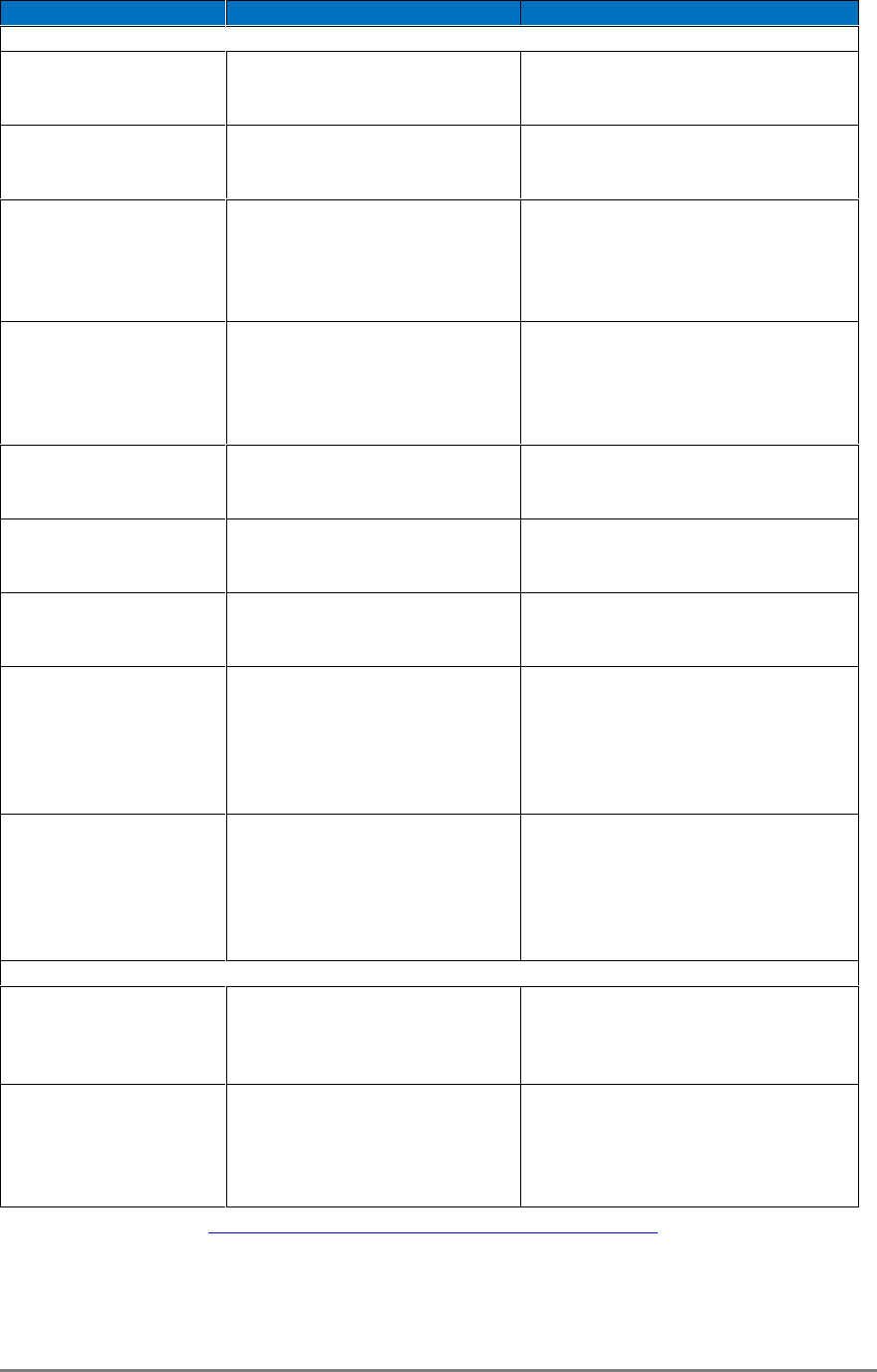

Annex I

Statutes available to the US President to reduce tariffs and other trade-related powers

(non-exhaustive list)

Congressional Statute

Conditions

Presidential powers

Limited powers or subject to conditions

Tariff Act of 1930

When the President finds the

public interest is served if the

country discriminates

New or additional duties if certain

conditions are met

Trade Expansion Act of

1962,

Section 232(b)

Finding of an adverse impact on

national security from imports

Impose tariffs or quotas as needed to

offset the adverse impact, subject to

procedural requirements

Trade Act of 1974,

Section 122

Fundamental US balance of

payments deficit

Impose tariffs up to 15 %, or

quantitative restrictions, or both for a

maximum of 150 days against one or

more countries with large balance of

payments surpluses

Trade Act of 1974,

Section 301

Foreign country denies the US its

trade agreement rights or carries

out practices that are

unjustifiable, unreasonable, or

discriminatory

Modification of tariff rates

Trade Act of 1974,

Section 501

After considering certain

conditions

Authorisation to grant certain duty

preferences to articles from any

beneficiary developing country

NAFTA Implementation

Act of 1993, Section 201

When the President determines

it necessary within the confines

of the agreement

Proclamation of tariffs (modification,

rate reduction, additional duties)

Uruguay Round

Agreement of 1994,

Section 111

When the President determines

it necessary within the confines

of the agreement

Proclamation of tariffs (modification,

rate reduction, additional duties)

Dominican Republican-

Central America Free

Trade of 2005, Section

201

When the President determines

it necessary within the confines

of the agreement (limited tariff-

reduction authority under the

implementing legislation of the

FTA

Proclamation of tariffs (modification or

continuation of any duties, additional

duties)

Bipartisan Congressional

Trade Priorities and

Accountability Act of

2015, section 103

When the President determines

that existing duties or import

restrictions of foreign countries

are a burden for US trade

Proclamation of tariffs (modification or

continuation of any duties, additional

duties). However the President shall

notify his intention to Congress and

the delegation of authority is subject

to a number of restrictions.

Almost unlimited powers

Trading with the Enemy

Act of 1917, Section 5

During time of war

Fairly broad authority (investigate,

regulate, direct and compel, nullify,

void), plus the power to freeze and

seize foreign-owned assets of all kinds

International Emergency

Economic Powers Act of

1977, Section 203

National emergency to deal with

an unusual and extraordinary

threat outside the US

Fairly broad authority (investigate,

regulate, direct and compel, nullify,

void), however the President in every

possible instance shall consult the

Congress.

Source: C. Devereaux Lewis, Presidential Authority over Trade: Imposing Tariffs and Duties, CRS, 9 December 2016.